The Feminine Sexual Counter-Revolution and Its Limitations, Part 1

Posted By F. Roger Devlin On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled4,818 words

Part 1 of 2 (Part 2 here [2])

Wendy Shalit

Girls Gone Mild: Young Women Reclaim Self-respect And Find It’s Not Bad to Be Good [3]

New York: Random House, 2007

Now reissued as:

The Good Girl Revolution: Young Rebels with Self-Esteem and High Standards [4]

New York: Ballantine, 2008

Wendy Shalit first came to public attention in 1995 with a hilarious article in Commentary magazine about the rise and fall of co-ed bathrooms at Williams College (“A Ladies’ Room of One’s Own,” August 1995). Freshmen of both sexes were to share a dorm, and determined by consensus that separate men’s and women’s lavatories would be unnecessary. In fact, all the girls would have preferred separate facilities, but none wanted to admit it for fear of being thought prudish. One developed urinary-tract problems from her reluctance to make use of the co-ed restroom until a point of extreme urgency had been reached. Further investigation revealed that the men were not altogether pleased with the arrangement either. A kind of “Emperor’s clothes” situation had arisen in which a group was imposing something on its members that few or none of them actually wanted.

Shalit came to understand that the sexual revolution as a whole had a similar character: young people were “hooking up” not because they personally desired to but because they believed it was expected of them. The campus feminists pushing casual sex at Williams seemed deeply unhappy. Elsewhere, she met Orthodox Jewish girls — forbidden even to touch their fiancés before the wedding — doing just fine. Braving the shaming tactics of peers and some professors, she wrote a senior thesis on modesty. The project eventually became the book A Return to Modesty: Rediscovering the Lost Virtue [5] (New York: The Free Press, 1997), an investigation into the nature of modesty, drawing on the Bible, Rousseau, Kierkegaard, Jean-Paul Sartre’s girlfriend, works of visual art, popular records, and Mademoiselle magazine.

A Return to Modesty was greeted with outrage from predictable quarters, such as pornographers and feminists. Baby-boomer reviewers accused her of “trying to turn back the clock,” the New York Observer printed a front-page caricature of her dressed as an SS officer, and she received death threats (p. 5). Her nonchalance about this sort of criticism is fittingly expressed by the inclusion in this new book of her personal apple pie recipe: a pie in the face of her “bad girl” critics, so to speak (p. 263). Her self-assurance has no doubt been reinforced by the thousands of grateful letters and e-mails she has received from young women.

The most interesting personal experience she relates involved an invitation, following on the success of her first book, to appear on a PBS program called “If Women Ruled the World.” While preparing to interview her, “the producer began to explain what he wanted me to say: that a certain second wave feminist had saved womankind and that I, as a young woman, was grateful to her.” When she expressed reservations about the woman’s ideas, “the producer began to get impatient: ‘What you’re saying,’ he sputtered, ‘isn’t in the script!'” (p. 19). In the end, she was not interviewed. She came to enjoy the ludicrousness of a male television producer doing a “powerful women” documentary and telling his female interviewees exactly what to say.

Her new offering, Girls Gone Mild, is less ambitious than her earlier book, omitting philosophical speculation on the deeper nature of modesty in favor of reportage on social and sexual trends among young women. The work draws on “over 100 in-depth interviews with girls and young women ages twelve to twenty-eight; fifteen interviews with young men; and over 3,000 e-mail exchanges” as well as a fair amount of travel and discussion with professionals of various sorts.

She begins by describing the popular Bratz dolls, with high heels and lipsticky come-hither looks, now marketed to girls age 7 to 12. A glossy magazine designed to accompany the dolls asks its young readers to ponder such weighty questions as “Are you always the first in your group to wear the hottest new looks?” and “Do you love it when people look at you in the street?” (p. xvii). For their younger sisters, there is already a Bratz Babyz series — baby dolls with fishnet stockings and miniskirts (p. xv). Such merchandise influences girls’ behavior, of course. One reader wrote to Shalit of

two little girls who live on our street who are maybe five and seven who dress in platform shoes, miniskirts, belly shirts, etc. One day they saw some boys playing baseball on the field near our house and got all dressed up with makeup, purses, etc. to walk down there and show off. (p. xix)

There is now even a word for such children: prostitots. (Shalit does not mention the circumstance, highly suspicious to this reviewer, that widespread hysteria over “pedophiles” has developed simultaneously.)

On the other hand, she reports on girls who have staged successful boycotts (called “girlcotts”) of companies pushing immodest clothing (pp. 224–31). This counter-current appears to be gathering strength: The rate of virginity among teenagers has risen for ten straight years (p. 75).

This male reviewer’s eyelids got heavy, however, when the author went into the details of staging an amateur “modest fashion show” (pp. 170–72). While no doubt preferable to having girls modeling thongs or Frederick’s of Hollywood negligees, we might better advise them to limit the time and money they spend on personal adornment altogether. How about substituting an event where we dress the girls in barrels with shoulder straps and teach them the uses of various household cleaning agents?

Adolescents who have outgrown their Bratz dolls can move on to Gossip Girl, a popular series of novels that Shalit describes as “the Marquis de Sade for teens.” Readers are led to fantasize about having modeling contracts, closets bulging with designer fashions, drawers stuffed with diamond accessories, and complicated love lives involving a “best friend’s boyfriend.” One female character is described as “not afraid to play dirty to get what she wants” (pp. 181–82). Girls unable to invest the effort required to read the books now have the option of watching the television series.

By way of contrast, the author introduces the reader to “L. T. Meade,” or Elizabeth Thomasina Meade Smith (1854–1914), American author of 280 books for girls, including such racy titles as A Very Naughty Girl, The Rebel of the School, and Wild Kitty. These books were churned out with about the same speed as the Gossip Girl novels, but they all contained a moral message. By the end of each novel, writes Shalit, a “character defect was expunged, but the girl’s spirit remained in full force.” The reform often involves the heroine’s learning to consider the needs of others hurt by her previous self-centered behavior. Modest as Meade’s artistic aims were, her characters are distinct: each “naughty” girl is naughty in a slightly different way. The Gossip Girls are more or less interchangeable ciphers compounded of greed, lust, and cunning (pp. 184–86). Home-schoolers take note: you may want to consider passing over Barnes & Noble in favor of an antiquarian shop.

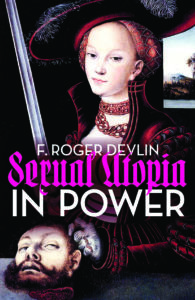

[6]

[6]You Can buy F. Roger Devlin’s Sexual Utopia in Power here. [7]

Many of Shalit’s anecdotes involve the strange new “generation gap” between baby-boomer parents and their offspring. Those old enough to remember when “the establishment” was a fighting term will be amused to read of rebellious teenage girls who declare “we’re the establishment, because nobody else wants to establish things” (p. 60).

The boomers thought — and still think — that courtship rituals and marital fidelity were mere shackles upon healthy desire. So they encourage their own children to do as they please. But the old rules were less shackles than guideposts; the young feel not liberated but lost without them. In other words, being told to “do whatever you want!” is unhelpful to adolescents still trying to figure out what they want. Often, their parents’ well-meaning encouragement is experienced by them as pressure to engage in sexual behavior they do not truly desire. Girls report having sex with strangers simply in order to “fit in.” One teenage boy sobs, “I don’t think my mom loves me,” because she does nothing to prevent his sleeping with an older woman (p. 8).

Commendably, the author devotes space to aspects of popular culture many writers (and possibly some readers of this Website) deem beneath their notice, such as Cosmopolitan magazine. She asks rhetorically:

Does it even matter what the women’s magazines say? “Serious writers” often tell me that “we all know” women’s magazines are not to be taken seriously. I beg to differ. The intelligentsia’s dismissal of Cosmo masquerades as sophistication but could hardly be more clueless. Perhaps it is necessary to state the obvious: The reason these magazines are available in every supermarket everywhere is that tens of millions of women are buying and reading them. (pp. 82–83)

Indeed, Cosmopolitan is the top-selling magazine in American college bookstores. It is not too much to call it an important part of an American woman’s education. When the author mentioned to a young, religiously observant woman that some people do not think Cosmo should be taken seriously, she “was shocked and drew in her breath sharply: ‘Are you kidding me? Cosmo? It’s, like, the Bible!'”

An editor at Seventeen magazine told her:

Honestly, I didn’t think much of teen mags before working with one, but I know that girls take Seventeen very seriously. Sometimes it scared me to learn just how much girls really looked to the magazine for advice. You wouldn’t believe the kinds of questions they would ask — things they should have been asking their parents but couldn’t or wouldn’t. (p. 83)

In other words, these cheap, mass-produced publications command tremendous moral authority with their readership: how well are we to suppose the selection process for editors ensures their ability to measure up to the responsibility?

Women’s magazines, in contrast to those marketed to men, contain almost nothing but advice. Men do seek advice, of course, but usually in particular and limited areas where they already have their goal in view. Women are comparatively rudderless. “The one thing I heard over and over” from interviewees, Shalit says, “was how desperate they were for a new set of role models” (p. xi). So much for the independent women feminism promised us.

Indeed, if our natural perceptions were not distorted by 40 years of feminist cant about “women leaders,” it would be perfectly obvious that most women feel a strong need for guidance, and this is one reason marriage is so important for their happiness. Their rage and frustration with men today is partly owing to men’s failure to provide them with the loving but firm leadership they require.

Shalit devotes one chapter to profiling young women who are actively speaking out in favor of premarital chastity. It is remarkable that most of them are black. The author notes that black colleges such as Spellman have stricter parietals than elite, mostly white Northeastern institutions such as the one she herself attended, and that “all the writers who have attacked me, calling modesty an ‘elite white’ concept, are in fact elite white people” (p. 66). She even slips in some boilerplate about “offensive racist stereotypes” and “the painful legacy of slavery.” Readers of The Last Ditch are possibly aware that such “stereotypes” have a real biological basis: Africans are in fact less monogamous than Europeans. But the author is merely reporting what she sees when she writes about the prominence of black women in the modesty movement. What could account for it?

Shalit acknowledges that the taboo on honest discussion of race makes this a difficult topic to approach. She found just one sociologist willing to address it, under condition of anonymity. He told her simply: “Black women have paid the heaviest price from the sexual revolution in the United States” (p. 72).

Here is my conjecture. It is an old observation that sexual morality is most strict among people of moderate means; looser behavior occurs among the very rich (because they can afford it) and the very poor (because they do not calculate the consequences). The worst possible situation arises when the poor become artificially “rich,” by their own standards, through welfare payments. Now, the elite white brats who pioneered the sexual revolution on campuses in the sixties were able to draw upon the capital laboriously built up by parents toughened in depression and war. Low-intelligence underclass blacks, at the opposite extreme, get their babies subsidized by taxpayers; they are actually rewarded for not having a male breadwinner. You will find even less sexual fidelity among them than among white college kids or the Hollywood glitterati. Shalit, however, did not plumb the social depths of the housing projects. The black women she talked with are managing to keep their head above water, and this group, unsubsidized and in moderate circumstances, has the most to fear from male abandonment. Economic deterioration may eventually present many white women with a similar set of incentives. The criminal behavior of “Family Courts” in systematically rewarding female abandonment is delaying this development, however.

One of the many reasons for limiting sexual relations to marriage is that it reduces competition between persons of the same sex, making friendship and trust possible between them. Shalit devotes a chapter to this subject. In a traditional religious community in Israel, she watched women drop what they were doing and dance until they teared up with happiness whenever they learned that one of them was to be married. “The idea of women being truly happy for one another, without any reservations, was new to me and also very moving,” she writes (p. 134).

In America, by contrast, popular girls’ T-shirts carry messages such as “Do I Make You Look Fat?” and “Blondes are Adored . . . Brunettes are Ignored.” Among the motives behind the recent successful “girlcotting” of stores selling such shirts, in fact, is girls’ awareness that they encourage cliques and bullying among themselves (p. 225).

Reportedly, an increasing number of American girls are choosing to socialize only with boys because, as one such girl’s mother explains, “teen girls are often brutally manipulative and mean” (p. 128). Experts report that “girls are committing significantly more acts of violence than they did even one generation ago” (p. 243). The author relates disturbing stories of girls actually driven to suicide by the bullying of their “friends” (pp. 254–55).

Girls may be behaving so badly in part because it is what they are now being taught. The author tells of one mother who was “determined to raise a feminist.” By the time her little girl was 2, the nursery school was complaining of her bullying the 5-year-olds (she would jump up in order to hit them). The mother says, “I encouraged her to ‘go for it.'” Another female lawyer told her, “I am very suspicious of telling girls they need to be morally good. That’s sexism right there” (p. 251). Shalit quotes articles from the popular feminist magazine Bitch ridiculing selfless and considerate women and unfavorably contrasting them with others who show a “dark side” (p. 241). A certain Elizabeth Wurtzel has written a whole book titled Bitch in which she declares: “For a woman to do just as she pleases and dispense with other people’s needs, wants, demands, and desires continues to be revolutionary” (p. 242).

A highly successful women’s magazine editor has written a book of advice for young wives stating: “Giving, devoting, sacrificing . . . these are the actions of a good wife, no? No. These are the actions of a drudge, a sucker, a sap.” Instead, women are urged to emulate a wife who threw her husband’s clothes into the garden to teach him not to leave socks on the floor: “He understood I meant it.” Or another who wanted her husband to help with the laundry, and hollered at him: “Are you a f***ing retard that you don’t see me running up and down stairs? Listen to me and stop your bulls**t.” Or another who discovered this interpersonal skill: “Just stand there and start screaming. If you stand there and scream long enough, someone is going to realize that you’re standing in the middle of the room screaming [and ask] ‘Why are you screaming?'” (pp. 245–47).

What could be wrong with men these days that they refuse to commit?

It is remarkable that a woman with such traditional ideas about marriage, modesty, and feminine decorum never condemns feminism per se. Instead, Shalit claims to have perceived a “fourth wave” of the movement characterized by the rejection of pornography and casual sex. This reviewer is not sanguine about the possibility of an eventual Nth feminist wave coming along to solve all the problems created by waves 1 through (N – 1). Shalit does better when she acknowledges that feminism has “become a sort of Rohrschach test: the word itself has become almost meaningless — and can refer to diametrically opposed ideas” (p. 208). The young self-described feminists she quotes do sound extremely confused. They say things such as “I don’t think the first feminists wanted us to be more like men” (p. 218) and “Feminism has always been about valuing home life” (p. 222). Some are simply using “feminist” to mean feminine (p. 121).

My impression, however, is that a couple things have in fact persisted through all these waves and permutations: an emphasis on “empowerment” for women, and the presumption that men are to blame for most of their problems. In at least this minimal sense, Wendy Shalit might be called a feminist.

* * *

The present reviewer is entirely in sympathy with a return to feminine modesty and the limiting of sexual relations to marriage. But this allows plenty of room for disagreement as to how our society got so far off track and the best means of returning to normal, healthy courtship and monogamy. In particular, the notion that all our problems come from women’s making sex available outside marriage — and, consequently, that a “holding out for the wedding” strategy will make everything right again — deserves a close, critical look. Wendy Shalit’s writings provide a useful occasion for doing this. Her proposals have considerable limitations, in fact, most of which flow from a single source: feminine narcissism and its concomitant unconcern for the masculine point of view.

I wish to be fair, so I will point out that her first book, A Return to Modesty (hereafter abbreviated RM), contained glimmers of such a concern. Sexual harassment law, she complained, “treats men like dogs. It says to them, Down, boy, down! Don’t do X, because I say so” (RM, p. 102). She insightfully noted that women can elicit desirable male behavior through moral authority far more effectively than they could ever impose it through the police power of the state. This is far removed from the usual feminist mentality.

In her new book Girls Gone Mild (hereafter GGM), however, the male viewpoint is almost totally disregarded. (She acknowledges the neglect but offers poor reasons for it: GGM, p. 277.) She even describes her indignation at a woman who reminded her, after a long discussion of girls and their problems, that, after all, the boys have feelings too: “I was speechless. Emotional, dreamy girls are a thorn in our side, but when boys are romantic, their every tear is precious” (GGM, p. 90).

My point is not that we should coddle boys; I am simply calling attention to the difficulty Shalit, in common with most women, seems to have with putting herself imaginatively in the place of a male. There may well be an evolutionary explanation for this. Men instinctively protect women because the future of the tribe lies in the children they bear. Women have adapted to this state of affairs, and it colors their moral outlook. They do not spend much time worrying about the well-being of men. Even getting them to cook supper for their husbands is probably a triumph of civilization. Their natural inclination is to let men look after themselves and take their chances in life. At the same time, they count on men to shield them from the harsher aspects of reality, and become extremely indignant at any men who fail to do so. In other words, women are naturally inclined to assume that men must take responsibility for everyone, while they are only responsible for themselves and the children. Young, still-childless women have no one left to think about but themselves and easily fall into self-absorption. One popular women’s magazine is actually titled Self. I would not want the job of promoting a magazine of that title to men.

One aspect of female narcissism is a failure to think in terms of moral reciprocity. For example, here is a male columnist (Fred Reed) praising the intolerance of Mexican women for infidelity: “They can also be savagely jealous, to the point of removing body parts. But for this I respect them. Any woman worth having has every right to expect her man to keep his pants up except in her presence. He owes to her what she owes to him. Fair is fair.” This is the way a man thinks. A woman is more likely to think, “I get to do as I please and you get to do as I please: fair is fair.”

Does the reader suspect me of indulging in a cheap shot here? Consider, first, this passage from Shalit’s first book: “Many etiquette books, in both England and America, stressed a woman’s prerogative to greet a man on the street first, particularly if he was not a close friend. If she chose to greet him, he was obligated to respond in kind, but if she passed him by, there was absolutely nothing he could do about it” (RM, p. 56).

I do not mean to take issue with this rule of etiquette, which may well have a sensible rationale. My point is simply that its one-sidedness does not seem problematic or in need of explanation to Shalit. A man might at least ask whether there is some larger context that explains why, in this particular case, all rights should be with the woman and none with the man.

Second, let us consider the more important matter of sexual intimacy. Shalit is, of course, emphatic on a man’s lack of all sexual rights before the wedding. Referring to a girl whose boyfriend began “pressuring” her for sex after eight months of courtship, her assessment is: “If he’s pressuring you for sex, he probably doesn’t love you” (GGM, p. 29). Now, courtship is typically an interaction in which the man seeks sexual surrender from the woman and the woman seeks assurance of commitment from the man. Would the author sympathize with a man who reasoned: “If a woman is pressuring me for commitment, she probably doesn’t love me”? It does not sound like it: elsewhere, she approvingly quotes a woman who is “mortified” that when girls “hint to their boyfriends about marriage [they] find themselves dumped like garbage” (RM, p. 227). She even refers to the authority of another of her old etiquette books to show that “a young woman could assume that a man wanted to marry her if he simply spent a good chunk of time with her” (GGM, p. 28). (I’m guessing eight months would count as “a good chunk of time.”) In other words, women have the right to expect commitment from men, but men are bad when they seek sexual surrender from women; women’s instincts are morally valid, but men’s are not. (Moreover, Shalit never says a word about the legitimate male fear of divorce, which may well be why the young man in her anecdote was “pressuring” his girlfriend about sex rather than simply proposing marriage.)

An old-fashioned fellow might agree with the author’s disapproval of premarital sex, but probably on the assumption that she would at least acknowledge the husband’s claims after the ceremony. This assumption would be mistaken, however. Once the couple is married, the wife’s sexual desires and the duty of the husband to satisfy them become her exclusive concern (RM, pp. 114–15). When she comes across a case of a couple where the man was the party less eager for physical intimacy, her sympathy is once again with the woman; she asks: “If he has no interest in a mutually satisfying relationship, why not just leave?” (GGM, p. 177).

I believe Shalit is by no means unusually narcissistic, as women go. Most do take for granted men’s obligation to put women’s needs and desires before their own, and thus to feel no particular gratitude when men do so. Many women have no idea, for example, how intense a young man’s sexual urges can be, and are not inclined to treat this powerful force of nature with the necessary respect. Shalit never seems aware that men feel “pressured” by their own sexual urges, or that a normal, healthy young man who has dated a girl for eight months before making these urges known has already demonstrated a fair amount of self-control.

Lack of a sense of moral reciprocity and of an ability to empathize with men leads many women, in fact, into a kind of schizophrenic attitude toward male desire. Most of the time they complain about how annoying it is and seem to wish it would go away entirely. But they do, of course, want some man to marry them. In other words, men’s sexual desires are supposed to be weak enough never to inconvenience women, but at the same time strong enough that they gladly exchange all their independence and most of their income whenever some woman does, after all, decide to take a mate. The desideratum would appear to be a man whose natural urges are like a faucet that women could turn on and off at their own convenience.

It is true that actual men fall short of this “dildo ideal,” as it might be called. No restoration of feminine modesty is going to change the situation, however, or eliminate the need for women to compromise with men. Children who insist on having everything their own way eventually learn that no one wants to play with them anymore; women who follow Wendy Shalit’s advice of “waiting and keeping their standards high” may find that the wait lasts all the way to menopause.

When the sexual revolution began, women imagined that the “slavery” of marriage was unfairly standing between themselves and endless erotic fulfillment. Forty years later, many are imagining instead that the availability to men of sex outside marriage is standing in the way of their wedding. “If other women were not sluts,” they reason, “the man of my dreams would be forced to discover my true value and come crawling to me with a diamond ring.” One of the interviewees from Shalit’s first book, for example, complains: “After three dates when I wouldn’t sleep with [a certain man], he dumped me, just like that! If you ask me, it’s because it’s way too easy for them. Why should they waste time with a girl like me when they can get it for free?” (RM, p. 104).

Now, how does the woman know this is the reason he “dumped” (stopped courting) her? Never once have I heard a woman say: “I am such a pain in the derrière that after just three dates men are charging for the exit.” Appealing to the supposed universal availability of sex has become a way for women to avoid facing the reality of rejection. Men break off courtships for all kinds of reasons: they may sense that a particular girl might not be faithful, is not careful with money, has too many bad habits, or just plain is not for them. Holding out for wedding rings is not going to solve these women’s problems and allow them to live happily ever after. If we could wave a magic wand and cause extramarital sex to disappear overnight, many women would be shocked to discover that handsome movie stars were still not flocking to their doorsteps with flowers and chocolates.

Indeed, I have heard men remark on the oddity that sex seems to be the only card women have to play in the dating game any more. They do not know how to manage a household, raise children, or treat a husband. Instead, like prostitutes, they think entirely in terms of maximizing the return they get on sex. Even Shalit acknowledges an inability to cook at the time of her marriage. (That apple pie recipe of hers begins, “You will need two frozen premade pie crusts . . .”) A renewed focus on feminine modesty, while welcome, will not by itself prepare young women for their domestic duties. The attitude that “I’m too good to sleep around” in the absence of anything to offer men besides sex may result not in any epidemic of marriage proposals but in widespread spinsterhood enlivened only by occasional readings of The Vagina Monologues, the lesbian-feminist play in which women gush over how wonderful their own private parts are.

Source: http://www.thornwalker.com/ditch/ [8]