The Monumental Civic Sculpture of Donald De Lue

Posted By Andrew Hamilton On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,236 words

For nearly 50 years between 1940 and 1988, Donald De Lue (1897–1988) may have executed more monumental public commissions than any other sculptor of his generation. An iconoclastic figurative artist in an era dominated by apostles of ugliness in art, art criticism, and academia, De Lue’s monumental sculpture adorns such sites as Valley Forge, the Gettysburg Battlefield, Omaha Beach at Normandy, and the 1964 New York World’s Fair.

His art has been described as a “traditionalist blend of classical myth, national symbolism, and spiritualized personification of emotions.” Though essentially realistic, De Lue’s work is nevertheless imbued with a profound sense of romantic poetry.

De Lue was in the great tradition of Western humanism beginning with the classical sculpture of the Greeks, followed by Michelangelo during the Renaissance and, in the 19th century, Auguste Rodin.

De Lue’s sketches, medals, and smaller sculptures are still prized. Currently, one of his lesser works, Jason, Triumph Over Tyranny [2], a gilded bronze statuette measuring 18 1/2″ high, is being auctioned for an estimated $25,000– $30,000, with a starting bid of $12,500.

Bursting the Bounds

Donald Harcourt De Lue was born Donald H. Quigley in Boston in 1897 to an Irish American father and a French American mother whose maiden name he eventually adopted as his own.

After showing some drawings at age 12 to Boston sculptor Bela Pratt, De Lue became an apprentice in the studios of Pratt and his assistant Richard Recchia.

There, and while taking courses at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where Pratt taught, he began honing his skills as a sculptor.

In 1918 De Lue sailed to France as a merchant seaman. From 1918 to 1922 he worked in studios in Paris as an assistant to Paul Manship and Italian-born Alfredo Pina, in Lyons and London (where he assisted Bryant Baker).

De Lue was influenced also by the work of Pina’s rival, Antoine Bourdelle. Both Pina and Bourdelle had been pupils of Auguste Rodin, the greatest sculptor of the 19th century.

Returning to the US in 1922, he became chief modeler in the New York City studio of Bryant Baker from 1923 to 1938.

At age 36, De Lue married (Martha) Naomi Cross. De Lue’s successful career dates from this time. His marriage lasted until his wife’s death 49 years later. The couple remained childless by choice in order to pursue his work; Naomi served as his business agent.

In what must surely be a rare occurrence, his wife transformed him from a hard-drinking, free-spending artist into a disciplined worker who settled down and learned to save money.

In 1938 De Lue was named runner-up in a competition for the Federal Trade Commission Building in Washington, DC. This led to several government commissions, the first of which were marble reliefs [4] (Justice and Law) for the new federal courthouse in Philadelphia.

From then on he worked independently as a sculptor.

The artist continued to execute architectural sculpture throughout his career. Architectural sculpture is sculpture used in the design of a building, bridge, mausoleum, or similar project, usually integrated with the structure, but including freestanding works if they are considered part of the original design.

De Lue created the relief sculptures on the doors of the Father Divine monument (Divine was a black preacher) in Woodmont, Gladwyne Pennsylvania, The Portal of Life Eternal [5] (1967–70) (click on image to enlarge).

He taught at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design in New York City during the early 1940s.

Succeeding Paul Manship as president of the National Sculpture Society from 1945–1948, during the postwar years De Lue won most of the awards available to a young sculptor.

In 1951 he received a commission to create seven works for a memorial to the fallen soldiers of D-Day located on Omaha Beach in Normandy, France, including The Spirit of American Youth [6] (1953–56).

In later years, De Lue and his wife lived in Leonardo, New Jersey, a small seashore community with a bayside beach and long-distance view of lower Manhattan. Though he continued to maintain his New York City apartment, it was in the Leonardo studio that many of his largest statues were made.

De Lue’s smaller works can be found in many museums and private collections across America.

An example of these, The Knight Crusader [7] (painted and carved wood sculpture, c. 1944) exudes a sense of mythological heroism in its depiction of a powerful, muscular knight kneeling in full armor with shield and broadsword. Alexander Astride Bucephalus [8] (bronze, 1956–1986) is a somewhat similar creation.

De Lue was also a prolific designer of medals and medallions, executing 26 commemorative medals for the Hall of Fame for Great Americans, the Daughters of the American Revolution, and the National Medal of Science among many others.

Against the Apostles of Ugliness

Most sculpture produced in the 20th century differed radically in form and content from that of the past. Generally, it explored the same directions as painting. Movements in both media even shared the same names: cubism, futurism, constructivism, Dada, surrealism, abstract sculpture. A great deal was “constructivist sculpture” created by means of construction and assemblage.

Although photography is often blamed for the disappearance of figurative art in the 20th century, the real culprit has been the avant-garde urges of artists and the critical establishment. In fact, critics, as Tom Wolfe proved in The Painted Word (1975), ultimately far outstripped creative artists in the power to dictate public tastes and artistic fashions.

De Lue’s deeply held belief in Western spiritual ideals and the classical tradition led him to become one of the most articulate and outspoken critics in the New York art world of the 1950s and 1960s against the depredations of abstract and modern art.

De Lue told the New York Times in 1951: “We [abstract and representational sculptors] don’t like each other. They think we’re old hat and we think they’re incompetent.”

Though unapologetically representational and clearly influenced by classical, neoclassical, and realistic traditions, De Lue’s best-known works possess a stylized quality personifying the spiritual, and make generous use of patriotic symbols and classical mythology.

According to Jonathan L. Fairbanks of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston:

His sculpture demonstrates artistic links to both Greco-Roman and late Renaissance sculptors. He emulated the exuberant gestures and energetic composition such as those found at Pergamum. The mature Michelangelo especially inspired De Lue to compose his figures with mannerist proportions, emphasized with highly articulated musculature. However, by combining these older influences with the ideas and techniques acquired during his stay in Europe. . . De Lue developed his own synthesis.

De Lue’s Monumental Public Sculpture

De Lue’s sculptures ranged from near-neoclassical to mannerist in the figurative tradition.

Among the near-neoclassical works are statuary of American patriots such as George Washington, Master Mason (bronze, Main branch, New Orleans Public Library, 1959) and George Washington at Prayer (bronze, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, 1965–67).

Thomas Jefferson [11] (bronze, Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, 1975) was based in part on a 1785 portrait bust by French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon. De Lue conceived Jefferson as striding; symbolic iconography included holding a quill pen, the Declaration of Independence, and the Bill of Rights in his left hand. The thirteen stars on the base represent the thirteen colonies.

The Special Warfare Memorial Statue (bronze, Fort Bragg, North Carolina, 1969), the first Vietnam War memorial in the United States, depicts a Special Forces sergeant in jungle fatigues carrying an M-16 rifle. One foot is crushing a snake, symbolic of tyranny in the world, on a rocky ledge.

The statue cost $100,000 to erect. John Wayne, co-director and star of the movie The Green Berets (1968), and Barry Sadler, composer of the song “The Ballad of the Green Berets” [13] (1966), each donated $5,000 toward its creation; Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara donated $1,000, and Special Forces soldiers around the world contributed the rest.

Leander Perez [14] (bronze, Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, 1977) is a tribute to the well-known segregationist politician.

Turning from the quasi-traditional to the more mannered or romantic works, we have the 5-ton Quest Eternal (bronze, Prudential Tower, Boston, 1967), an allegorical male nude with face turned skyward and arm extended to the heavens along the line of his gaze, palm out.

Three Confederate monuments at the Gettysburg National Military Park in Pennsylvania are The Soldiers and Sailors of the Confederacy (bronze, 1964–65), The State of Louisiana Monument [16] (bronze, 1967–69), and The State of Mississippi Monument (bronze, 1970-73).

The Mississippi monument, mounted on a solid granite base, shows two soldiers of Confederate General William Barksdale’s Mississippi Brigade. The standard bearer lies mortally wounded against a tree stump as a second soldier, swinging a rifle over his shoulder, grasps the barrel end with both hands, stepping over his fallen comrade to defend the fallen flag. The work represents the day’s hand-to-hand fighting.

The Boy Scout Memorial [17] (bronze and granite, Washington, D.C., 1964), located at the 1937 site of the first National Scout Jamboree, depicts three purposefully striding figures: a uniformed Boy Scout with a walking stick in hand flanked by two allegorical adult figures, one male and one female, representing American manhood and womanhood respectively. The nude man is carrying a cloth that blows across his midsection, concealing his genitals, as in De Lue’s Rocket Thrower and other works. The partially-clad female is carrying an eternal torch with a gold-colored flame.

Rocket Thrower

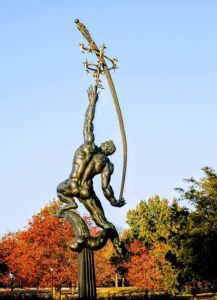

The Promethean Rocket Thrower (bronze, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, Queens, New York, 1964), at the time of its execution one of the largest and most prominent public sculpture commissions in America for the previous 50 years, was a notable feature of the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair.

The 43-foot-high figure is hurling a rocket emitting an arcing trail of flames heavenward with his right hand while reaching toward a constellation of gilded stars with his left. The statue soared above the fair, symbolizing humanity’s conquest of outer space.

De Lue envisioned the Rocket Thrower as “the spiritual concept of man’s relationship to space and his venturesome spirit backed up by all the powers of his intelligence for the exploration of a new dimension.”

The nearby Unisphere [19] was a large mesh stainless steel globe displaying the continents and orbital patterns in space. Viewed from the edge of the pool, the Unisphere had the dimensions Earth would have if viewed from a height of 6000 miles.

Punctuating a key axis extending out from the Unisphere at a site called the Court of the Astronauts, Rocket Thrower, the Fair’s artistic centerpiece, was the largest and most expensive ($105,000) of the official sculpture commissions.

The monumental statue was based on designs for the theme “man conquering space” that De Lue had prepared in the late 1950s for the Union Carbide Building in New York City.

In 1962 the sculptor signed a contract to create the piece and was given less than six months to execute a full-scale model. By June 1963 the full plaster model was completed and shipped to Italy, where casting at the Fonda Artista in Via Reggio took nearly a year. The sculpture was installed just prior to the fair’s opening on April 22, 1964.

Over the years the statue’s surfaces have deteriorated, as seen in the accompanying photograph, and its structural integrity has become compromised. Prejudices have deterred efforts at conservation. In order to obtain an idea of what it originally looked like, click here to see a color postcard [21] dating from the time of the fair.

Today it is difficult to conceive that at the dawn of the space age such national self-conceptions and aspirations and soaring optimism were still so prevalent in this country that they could find expression in a major work of civic art such as Rocket Thrower.

One of Donald De Lue’s last monumental sculptures was a larger-than-life statue of Jim Bowie, William Travis, and Davy Crockett commissioned by a wealthy patron for the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas. The finished work was deemed “too violent” for placement in a sacred chapel by the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, and the resulting impasse over its proper siting was never resolved.

As a Boston art gallery closely identified with De Lue’s oeuvre summarizes:

In its use of national symbolism, classical mythology, and the personification of spiritual ideas, his work, though squarely within the figurative tradition, possesses a depth of meaning beyond the sheerly literal. A leader of the traditionalists in controversies pitting them against modernists for commissions, museum shows, and critical recognition, he outlived his bitterest foes to gain new recognition and new audiences. His exquisite craft, special vision, and artistic dedication have made him one of the greatest of American traditionalists, whose monumental and commemorative sculptures are appreciated by all who hunger for masterful craftsmanship and classical values in art.

Donald De Lue died in New Jersey in 1988, just short of his 91st birthday. He and his wife are buried in Old Tennent Churchyard [22] in Monmouth County. The epitaph on his tombstone [23] (which also contains a sculptural relief) reads:

Sculptor

Washington at Valley Forge

Omaha Beach, Normandy, Fr.

Gettysburg, Louisiana and Mississippi state memorials at Gettysburg

Quest Eternal, Pru. Ctr, Boston

Green Beret, Fort Bragg, N.C.

Boy Scout Group, Wash. D.C.

Harvey Firestone, Akron, O.

The Rocket Thrower, N.Y.

Further reading:

D. Roger Howlett, The Sculpture of Donald Delue: Gods, Prophets, and Heroes [24] (Boston: David R. Godine, 1990)