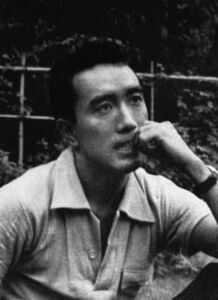

Yukio Mishima

Posted By Kerry Bolton On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledYukio Mishima was born into an upper middle class family in 1925. Author of a hundred books, playwright, and actor, he has been described as the “Leonardo da Vinci of contemporary Japan,” and is one of the few Japanese writers to have become widely known and translated in the West.

The Dark Side of the Sun

Since World War II, the West has forgotten the Shadow soul of Japan, as Jung would have termed it, the collective impulses that have been repressed by ‘Occupation Law’ and the imposition of democracy. The Japanese are seen stereotypically as being overly polite and smiling business executives and camera snapping tourists. The emphasis has been on the soft counterpart of the Japanese psyche, on the “chrysanthemum” (the arts) as Mishima puts it, and the repression of the “sword” (the martial tradition). The American anthropologist Ruth Benedict wrote of the duality of the Japanese using this symbolism in her The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, to which Mishima referred approvingly. He insisted that Japan return to a balance of the arts and the martial spirit, to what, again referring to Jung, would be called individuation, in allowing the repressed Shadow archetype to reassert itself. Mishima was himself that synthesis of the scholar and the warrior, who rejected pure intellectualism and theory in favor of action.

The Way of the Samurai

Mishima’s aesthetic was the beauty of the violent death, the death of one in his prime, an ideal common in classical Japanese literature. As a sickly youngster, Mishima’s ideal of the heroic death had already taken hold: “A sensuous craving for such things as the destiny of soldiers, the tragic nature of their calling . . . the ways they would die.”

He was determined to overcome his physical weaknesses. There is much of the Nietzschean “Overman” about him, of self-overcoming personal and social restraints to express his own heroic individuality. His motto was: “Be Strong.” (He had read Nietzsche during the war.)

He was determined to overcome his physical weaknesses. There is much of the Nietzschean “Overman” about him, of self-overcoming personal and social restraints to express his own heroic individuality. His motto was: “Be Strong.” (He had read Nietzsche during the war.)

World War II had a lasting impact on Mishima. Along with his fellow students, he felt that conscription and certain death waited. He became chairman of the college literary club, and his patriotic poems were published in the student magazine. He also co-founded his own journal and began to read the Japanese classics. He associated with a literary group, Bungei Bunka that believed war to be holy. The Japanese Romanticists were another literary group avowing the same principles with which Mishima was in contact. Mishima barely passed the medical examination for military training. He was drafted into an aircraft factory and several other such jobs.

In 1944, he had already had his first book, Hanazakan no Mori (The Forest in Full Bloom) published, a considerable feat in the final year of the war, which brought him instant recognition.

The Will to Health

In 1952, Mishima, established as a literary figure, traveled to the USA. Sitting in the sun in transit aboard ship, something he had been unable to do in his youth because of his weak lungs, Mishima resolved to match the development of his physique with his intellect.

His interest in the Hellenic classics took him to Greece. He wrote that, “In Greece there had been however an equilibrium between the physical body and intelligence, soma and sophia . . . ” He discovered a “Will towards Health,” an adaptation of Nietzsche’s “Will to Power,” and he was to become almost as noted as a body builder as he was a writer. In 1966 Mishima wrote; “The goal of my life was to acquire all the various attributes of the warrior.”

His ethos was that of the Samurai Bunburyodo-ihe: the way of literature (Bun) and the Sword (Bu), which he sought to cultivate in equal measure, a blend of “art and action.” “But my heart’s yearning towards Death and Night and Blood would not be denied.”

He expressed the Samurai ethos: “To keep death in mind from day to day, to focus each moment upon, inevitable death, . . . the beautiful death that had earlier eluded me [World War II] had also become possible. I was beginning to dream of my capabilities as a fighting man.” In 1966, he applied for permission to train at the army camps.

In the spirit of Bunburyodo, Mishima’s novels plotted the course of his life. In 1967, Runaway Horses had as its hero a right-wing terrorist who commits hara-kiri after stabbing to death a businessman.

Already in 1960 Mishima had written his short story Patriotism, in honor of the 1936 Ni ni Roku rebellion of army officers of the Kodo-ha faction who wished to strike at the Soviet Union in opposition to the rival Tosei-ha, who aimed to strike at Britain and other colonial powers. The Kodo-ha officers had mobilized 1,400 men and taken Tokyo. However, Emperor Hirohito ordered them to surrender.

The incident impressed itself on Mishima. In Patriotism the hero, a young officer, commits Hara-kiri, of which Mishima states: “It would he difficult to imagine a more heroic sight than that of the lieutenant at this moment.”

Mishima was again to write of the incident in his play Toka no Kiku and in his 1966 novel The Voices of the Heroic Dead. Here he criticizes the Emperor for betraying the Kodo-ha officers and for renouncing his divinity after the war as a betrayal of the war dead. Mishima combined these three works on the rebellion into a single volume called the Ni Ni Roku trilogy.

Mishima comments on the Trilogy and the rebellion:

Surely some God died when the Ni Ni Roku incident failed. I was only eleven at the time and felt little of it. But when the war ended, when I was twenty, a most sensitive age, I felt something of the terrible cruelty of the death of that God . . . the positive picture was my boyhood impression of the heroism of the rebel officers. Their purity, bravery, youth and death qualified them as mythical heroes; and their failures and deaths made them true heroes in this world . . . .

In early 1966, Mishima systemised his thoughts in an eighty-page essay entitled Eirei no Koe (The Voices of the Heroic Dead), after which he decided to create the Tatenokai (Shield Society). In this work he asks, “why did the Emperor have to become a human being.”

In an interview with a Japanese magazine that year, he upheld the imperial system as the only type suitable for Japan. All the moral confusion of the post-war era, he states, stems from the Emperor’s renunciation of his divine status. The move away from feudalism to capitalism and consequent industrialisation in the modern state causes relationships to be disrupted between individuals. Real love between a couple requires a third focus, the apex of a triangle embodied in the divinity of the Emperor.

The Tatenokai

The following year Mishima created his own militia, writing shortly before this of reviving the “soul of the Samurai within myself .” Permission was granted by the army for Mishima to use their training camps for the mostly student followers he recruited from several right-wing university societies.

At the office of a right-wing student journal, a dozen people gathered. Mishima wrote on a piece of paper: “We hereby swear to be the foundation of Kokoku Nippon [Imperial Japan].” He cut a finger, and everyone else followed, letting the blood fill to the brim of a cup. Each signed the paper with their blood and drank from the cup. The Tatenokai was born.

The aims of the society were:

(i) Communism is incompatible with Japanese tradition, culture, and history and runs counter to the Emperor system;

(ii) the Emperor is the sole symbol of our historical and cultural community and racial identity; and

(iii) the use of violence is justifiable in view of the threat posed by communism.

The emblem that Mishima designed for the society comprised two ancient Japanese helmets in red against a white silk background. The militia was designed to be a “stand by the army,” described by Mishima as “the world’s least armed, most spiritual army.”

By this time, Mishima felt that his calling as a novelist was completed. It must have seemed the right time to die. He had been awarded the Shinchosha Literary Prize in 1954 for The Sound of Waves and the Yomiuri Literary Prize in 1957 for The Temple of the Golden Pavilion

. His novels Spring Snow

and Runaway Horses

had sold well in 1969, but Mishima started to feel the antagonism of the Left-wing dominated literary elite and his Sea of Fertility [a series of four books encompassing Spring Snow

, Runaway Horses, Temple of Dawn

, and The Decay of the Angel

] received the silent treatment. His sole defender at this time was Yasunari Kawabata, who had received the Nobel Prize for literature in 1968, Mishima missing out because the Nobel Prize committee assumed he could wait awhile longer in favor of his mentor. Kawabata considered Mishima’s literary talent as exceptional.

Mishima wrote of the intellectuals as:

The strongest enemy within the nation. It is astonishing how little the character of modern intellectuals in Japan has changed, i.e., their cowardice, sneering, ‘objectivity.’ rootlessness, dishonesty, flunkeyism, mock gestures of resistance, self-importance, inactivity, talkativeness, and readiness to eat their words.

The Hagakure

Mishima’s destiny was shaped by the Samurai code expounded in a book that he had kept with him since the war. This was the Hagakure, the best-known line of which is:

I have discovered that the way of the Samurai is death.

The Hagakure was the work of the seventeenth-century Samurai Jocho Yamamoto, who as a priest was to dictate his teachings to his student Tashiro. The Hagakure became the moral code taught to the Samurai, but did not become available to the general public until the latter half of the nineteenth century. During World War II, it was widely read, and its slogan on the way of death was used to inspire the Kamikaze pilots. Following the occupation it went underground, and many copies were destroyed rather than have them read by the Americans.

Mishima wrote his own encapsulation and commentary on the Hagakure in 1967. He stated in his introductory remarks that this is the one book that he has referred to continually in the twenty years since the war, and that during the war he had always kept it close to him.

Immediately following the war, Mishima relates that he felt isolated from the rest of literary society, which had accepted ideas that were alien to him. He asked himself what his guiding principal would be now that Japan was defeated. The Hagakure was the answer, providing him with “constant spiritual guidance” and “the basis of my morality.” Like all other books of the war period, this had become loathsome, to be wiped from the memory, but in the darkness of the times it would now radiate “its true light.”

The heroic death is the culmination of the life of the man of action. For the man of action death is the single point of the completion of one’s life. It must be taken at the right time. Mishima found the social and moral criticism of Jocho relevant to post-war Japan.

The Feminization of Society

The feminization of the Japanese male (contemporarily as a result of the influence of American democracy) was, Mishima pointed out referring to Hagakure, also noted by Jocho during the peaceful years of the Tokugawa era. The eighteenth-century prints of couples together hardly distinguish between male and female, with similar hairstyles, cut and pattern of clothes, even the same facial expressions, which make it impossible to tell who is the male and who the female. Jocho records in Hagakure that during his time, the pulse rate that differed between the genders had become the same, and this was noted when treating medical ailments. He called this fumigation “the female pulse.”

Celebrities Replace Heroes

Jocho condemns the idolization of certain individuals achieving what we’d today call celebrity status. Mishima comments:

Today, baseball players and television stars are lionized. Those who specialize in skills that will fascinate an audience tend to abandon their existence as total human personalities and be reduced to a kind of skilled puppet. This tendency reflects the ideals of our time. On this point there is no difference between performers and technicians. The present is the age of technocracy . . . differently expressed, it is the age of performing artists. It means specialization and therefore the confinement of the individual into a single cog.

The Boredom of Pacifism

Under pacifism and democracy, the individual is literally dying of boredom, rather than living and dying heroically.

Ours is an age in which everything is based on the premise that it is best to live as long as possible. The average life span has become the longest in history, and a monotonous plan for humanity unrolls before us.

After finding his place in society and the struggle is over, there is nothing left for youth, apart from retirement, “and the peaceful, boring life of impotent old age.” The comfort of the welfare state ensures against any need to struggle, and one is simply ordered to “rest.” Mishima comments on the extraordinary number of elderly who commit suicide. Now we might add the even more extraordinary number of youth that commit suicide.

Mishima equates socialism and the welfare state, and finds that at the end of the first, there is “the fatigue of boredom”; whilst at the end of the second there is suppression of freedom. People desire something to die for, rather than the endless peace that is upheld as a Utopia. Struggle is the essence of life. To the Samurai death is the focus of his life, even in times of peace. “The premise of the democratic age is that it is best to live as long as possible.”

The Repression of Death

The modern world seeks to avoid the thought of death. Yet the repression of such a vital element in living will become ever more explosive, as do all such inner-directed impulses. Here the psychologist Jung would concur. Mishima states:

We are ignoring the fact that bringing death to the level of consciousness is an important element of mental health . . . Hagakure insists that to ponder death daily is to concentrate daily on life. When we do our work thinking that we may die today, we cannot help feeling that our job suddenly becomes radiant with life and meaning.

Extremism

Mishima states that Hagakure is a “philosophy of extremism.” Hence, it is inherently out of character in a democratic society. Jocho stated that whilst the Golden Mean is greatly valued, for the Samurai one’s daily life must be of a heroic, vigorous nature, to excel and to surpass. Mishima comments that “going to excess is an important spiritual springboard.” There is something in this that is reminiscent of Nietzsche and of the heroic vitalism expounded in the west by D. H. Lawrence and Ernst Jünger and others.

Intellectualism

Of intellectuals, Mishima shares the same contempt as the other Thinkers of the Right who are attuned to the life force or elan vital that transcends the intellectualism that arises from the cities of civilizations in decline. Jocho had stated that:

The calculating man is a coward. I say this because calculations have to do with profit and loss, and such a person is therefore preoccupied with profit and loss. To die is a loss, to live is a gain, and so one decides not to die. Therefore one is a coward. Similarly a man of education camouflages with his intellect and eloquence the cowardice or greed that is his true nature. Many people do not realise this.

Mishima comments that in Jocho’s time there was probably nothing corresponding to the modem intelligentsia. However, there were scholars, and even Samurai themselves, who began to form themselves into a similar class “in an age of extended peace.” Mishima identifies this intellectualism with “humanism.” This intellectualism means, contrary to the Samurai ethic, “one does not offer oneself up bravely in the face of danger.”

No Words of Weakness

The Samurai in times of peace still talks in a martial spirit. Jocho taught that “the first thing a Samurai says on any occasion is extremely important. He displays with this one remark all the valor of the Samurai.”

Mishima comments that there is never a word of weakness uttered by a Samurai. “Even in casual conversation, a Samurai must never complain. He must constantly be on his guard lest he should let slip a word of weakness.” Another principle; “One must not lose heart in misfortune.”

The Flow of Time

Something of the cycles of a civilization from health to degeneracy and death, as Spengler and Julius Evola showed, are also portrayed in Hagakure by Jocho as “the flow of time.” Mishima points out that whilst Jocho laments “the decadence of his era and the degeneration of the young Samurai,” he observes “the flow of time,” realistically stating that it is no use resisting that flow.

As Jocho stated: “The climate of an age is unalterable. That conditions are worsening steadily is proof that we have entered the last stage of the Law.” This refers to the entering of three progressively degenerate stages according to the Buddhist cycles of history.

Jocho employs the analogy of seasons just as Oswald Spengler did in describing the cycles of a civilisation from birth, flowering, withering and death: “However, the season cannot always be spring or summer, nor can we have daylight forever. What is important is to make each era as good as it can be according to its nature.”

Jocho does not recommend either nostalgia for the return of the past, or the ’superficial’ attitude of those who only value what is modem, or ‘progressive’ as we call it today.

Julius Evola, the Italian ‘Thinker of the Right,” elaborating on the cyclical nature of history similarly recommended to young activists concerned at the demise of Western Civilization that they cannot return to the past nor prevent the present cycle. They must “ride the tiger,” see out the present era, and to lay the foundations for a cultural renewal.

A Samurai’s Destiny

November 25, 1970 was chosen as the day that Mishima would fulfil his destiny as a Samurai. Four others from the Tatenokai joined him. All donned headbands bearing a Hagakure slogan. The aim was to take General Mishita hostage to enable Mishima to address the soldiers stationed at the Ichigaya army base in Tokyo. Mishima and his lieutenant Morita would then commit Hara-kiri. Only daggers and swords would be used in the assault, in accordance with Samurai tradition.

The General was bound and gagged. Close fighting ensued as officers several times entered the general’s office. Mishima and his small band each time forced the officers to retreat. Finally, they were herded out with broad strokes of Mishima’s sword against their buttocks. A thousand soldiers assembled on the parade ground. Two of Mishima’s men dropped leaflets from the balcony above, calling for a rebellion to “restore Nippon.”

At mid-day precisely Mishima appeared on the balcony to address the crowd. Shouting above the noise of helicopters he declared: “Japanese people today think of money, just money: Where is our national spirit today? The Jieitai [army] must be the soul of Japan.”

The soldiers jeered. Mishima continued: “The nation has no spiritual foundation. That is why you don’t agree with me. You will just be American mercenaries. There you are in your tiny world. You do nothing for Japan.” His last words were: “I salute the Emperor. Long live the emperor!”

Morita joined him on the balcony in salute. Both returned to Mishita’s office. Mishima knelt shouting a final salute, and plunged a dagger into his stomach, forcing it clockwise. Monta bungled the decapitation leaving it for another to finish it. Morita was then handed Mishima’s dagger but called upon the swordsman who had finished off Mishima to do the job, and Morita’s head was knocked off in one swoop. The remaining followers stood the heads of Mishima and Morita together and prayed over them.

Ten thousand mourners attended Mishima’s funeral, the largest of its kind ever held in Japan. “I want to make a poem of my life” Mishima had written at 24 years of age. He had fulfilled his destiny according to the Samurai way:

To choose the place where one dies is also the greatest joy in life.

After his death, his commentary on the Hagakure became a best-seller.

Chapter 12 of K. R. Bolton, Thinkers of the Right: Challenging Materialism (Luton, England: Luton Publications, 2003).