Screamin’ & Hollerin’ the Blues:

The Myth of Authenticity & White Culture

Posted By

Alex Kirillov

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

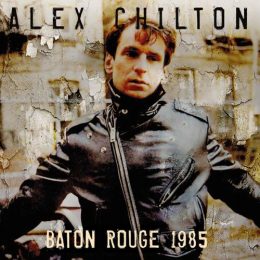

I recently purchased Alex Chilton’s Baton Rouge 1985 which had been released by Klondike Records late last year. Most readers, if familiar with Chilton at all, know him as the teenage leader of the Box Tops, whose 1967 hit “The Letter” rocketed them to international fame, or as the primary songwriter behind the proto-indie rock band Big Star. A fewer number will recall Chilton’s punk/rockabilly phase (1976-1980) or his penultimate turn as an interpreter of R&B and soul music.

Baton Rouge 1985 is a live album that catches Chilton at the peak of this later stage of his career playing to a mildly uninterested audience. Overall the performance is good and the band adheres to the ramshackle style Chilton had embraced since the demise of Big Star in 1974. One song in particular from this set struck me with an eerie resonance –Chilton’s cover of Elmore James’s Dust my Broom. Upon hearing this song I had an involuntary recall of all the blues music I had forced myself to ingest as a teenager some twenty odd years ago.

Before the internet, music fans were usually turned on to bands by other fans. Music publications, especially the English variants Mojo and Uncut, would then supplement this aesthetic development by closely detailing the histories and influences of these popular bands, as well as reopening interest in lesser known artists.

For teenagers in the eighties and nineties who began to listen to sixties and seventies artists like the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin there was a concerted push on the part of the music press to emphasize these bands’ blues and R&B antecedents. I believe this push occurred for three reasons: 1) Music journalists legitimately wanted to present these influences as part of a comprehensive narrative of the band. 2) The record industry wanted to reissue and sell more of this older music to a newer audience. 3) The promotion of the narrative that these antecedents were more authentic than the artists who came after them.

It seems intuitively correct to cast the older artist, the artist that is doing the influencing, in a light of greater authenticity than the younger artist. The twist in the case we are discussing is that not only is the older artist historically antecedent to the younger, he is also racially distinct. For example, an Eric Clapton fan that develops more than a cursory interest in his favorite guitarist dives into Clapton’s biography and in so doing discovers the name “Robert Johnson.” Johnson was poor, he played guitar, died under mysterious circumstances, was part of a subjugated racial minority and he lived in a time and place that has been erased by modernity –his legend is essentially the legend of The Other. Anyone can grasp and articulate this; what the music press and the music industry did then was consciously conflate this otherness with the idea of authenticity.

Part One

What exactly are we talking about when we use the term “authenticity” in regard to a piece of music or art? The intuitive response is most likely one that conflates the concept of authenticity with that of honesty. However, on closer examination it seems obvious that the concept of authenticity has to reach deeper into our sense of experience than mere honesty. Honesty is something we usually apply to some proposition that is immediate and contingent upon the context of the situation in which it is uttered. Authenticity seems like it contains some degree of honesty, but we can say that a character in a novel, who is a thief and a liar, is portrayed with authenticity. The truth we ascribe to the notion of authenticity seems to reach out into the greater context surrounding the subject who grasps it; authenticity seems to bear upon the narratives we have deemed historical, or at least historically accurate.

To my mind, there seems to be two types of authenticity: one is the immediate kind that we seem to innately conflate with honesty –this is an authenticity of expression. The second seems to be an authenticity that we ascribe to works that we are consciously aware of existing outside of our immediate cognitive grasp of them. This type of authenticity has to do with art as artifacts of history and culture. Our appreciation of these works involves an objective analysis, one involving grander and more ambiguous concepts than the more immediate, conflated idea of authenticity.[1] [2]

As whites, separated from a sense of having our own indigenous culture, we are constantly on the look out for signifiers of authenticity. This is not necessarily a bad thing, and unlike a run-of-the-mill post modernist I’m not going to argue that authenticity, in the historical-contextual sense that I am favoring, is merely a myth. To be more precise, authenticity might be mythlike but we have no need to be dismissive of myths or to cast them in a pejorative light. Myths are not lies, some of them may stem from fabrications, but essentially by taking on what we call mythic proportions these stories transcend the conceptual bounds of deception, and even entertainment for that matter.

Myths, as Eliade would argue in The Myth of the Eternal Return are originary stories that are central to the communal lives of different volkish groups. In this respect, the characters populating the myths have a certain vagueness that allows the members of the community to imagine themselves cast in the various roles of the story –these myths carry a germ of universalism throughout the community but it is a universalism that only makes sense in the context of that community and its narratives.

Returning to modern western society and its integration of the blues, we find the sense of vagueness in relation to the characters intact, hence today’s listener can identify with Eric Clapton as a person and an artist, can identify with Clapton’s devotion to Robert Johnson as a source of artistic inspiration, and to some extent can identify with Robert Johnson himself. At this point though the heterogeneity of Johnson, by virtue of his racial difference, comes to the fore and with it, the issue of authenticity.

In their book, Faking It, Hugh Barker and Yuval Taylor give a succinct account of the process of idealization black music underwent in the western consciousness:

Back in the eighteenth century, Jean-Jacques Rousseau popularized the idea of the “native” as a “noble savage,” the embodiment of Western virtues, uncorrupted by civilization; the concept was applied equally to Polynesians, American Indians, and Africans, enslaved or not. But by the twentieth century, with the influence of Darwin and Freud, it was primarily the Negro who had become idealized, and this time as the primitive -brute, savage, untamable- pure id, and therefore profound.[2] [3]

In this passage, and for most of the chapter from which it is taken, it is argued that the idea of authenticity that has developed in our society has arisen from the conflation of the concepts of authenticity and primitivism. It ought to be noted that as liberals themselves, Barker and Taylor have no qualms with granting indigenous black music the seal of authenticity, their concern is with the pedigree of that seal being contingent upon the perceived primitive nature of blacks. For Barker and Taylor this primitivism, as it exists in the Western mind is the result of a misperception of black culture, a misperception that occurs when a part of the culture, e.g., rural blues, is taken as being representative of the totality of authentic black culture. On this view of misperception, more sophisticated music, like that of John Coltrane for instance, is dismissed because its sophistication seems to have been inculcated by a white culture that stresses theory, discipline and professional presentation.

This particular analysis, which is grounded in an antiquated notion of authenticity, seems correct within the context of the historical actors it is aimed at in the book: the Lomaxs and their audience in the early twentieth century. It is worth pointing out though that by adhering to the politically correct notion that blacks have collectively endured a degree of persecution unknowable by whites Barker and Taylor are essentially claiming that authenticity, in the case of black music, is contingent upon suffering. Needless to say, this is another case of conceptual conflation.

Previously we examined the idea of authenticity of expression: the conflation of the concepts of authenticity and honesty and deemed this to be something people grasp in an intuitive and immediate way. In contrast, this coupling of authenticity with suffering falls into the second category of authenticity, which I call artifactual authenticity, i.e., an authenticity that we ascribe to works that we are consciously aware exist outside of our immediate cognitive grasp of them. Faking It traces many variations of artifactual authenticity, the most interesting of which veer into a territory that seems indecipherable from authenticity of expression. I will discuss one of these strands near the end of this essay. For now it is necessary to contend with the artifactual strand that focuses on both suffering and otherness, specifically focusing on these concepts as they are applied in a communal sense

The music industry is governed by the liberal interests who have established the parameters of politically correct discourse yet it needs to make money; it is animated by a mentality that needs to balance Barker and Taylor’s criticism of white appraisal of black culture with the need for a broader sales market, one which would deny the importance of the ethnic aspect of a community. Out of this internal conflict the identification of authenticity with racial otherness emerges as being essential.[3] [4]

In regard to the three reasons stated at the beginning of this essay for the promotion of a narrative that prioritizes the authenticity of black culture over that of whites they are torn between reason 2 (The record industry wants to reissue and sell more of this older music to a newer audience) and reason 3 (The promotion of the narrative that these antecedents are more authentic than the artists who came after them).

The people who have promoted this collective strand of artifactual authenticity are animated not by reverence (as the myth believer is) but by a kind of cynicism. They are cynical towards the idea that their own racial antecedents ever did, or even could, achieve authenticity. It is important to point out that this kind of liberal cynicism, or to be more generous we might say skepticism, in the music industry is qualitatively different from the liberal cynicism that is endemic in western politicians. The politician who fights for open borders and unlimited immigration has no illusions that multiculturalism will enrich the white community he represents, he is merely serving the interests of his corporate donors. It is entirely possible that such an individual could deny the existence of authenticity outright. In contrast, the music journalist who propagated the myth of authenticity in relation to “the other” to some extent sought to mitigate a sense of lack he had found in art that had initially satisfied him aesthetically. The journalist/fan is channeling a Faustian kind of desire to stretch beyond what he had once found satisfactory. This type of individual necessarily believes in authenticity but is inclined to imagine it as being located somewhere beyond his immediate plane of existence.

As part of this Faustian trajectory the journalist/fan, reaches back into the past and finds an alterity in racial otherness that cannot be understood or totally conquered. It can be commodified however and this to some extent mitigates the distress caused by the ascertainment of how the racial alterity is inherently resistant to assimilation into the white aesthetic narrative. The journalist/fan articulates the authenticity of the genre he is enthralled with in terms of it being unknowable outside of membership within the particular racial community that engendered it, but compensates for his distance from this community by turning the constituents of the genre into products.

There is something to be said of how both the politician and the journalist/fan are influenced by a sense of social guilt. I think that this element influences the rhetoric or the technique by which their respective narratives are put forward, but it does not have real bearing upon the kernel of their reasoning. The two types of reasoning, at their core, are heterogeneous to each other, yet they are both inherently cynical.

Part Two

The musical revolution of the sixties was a time not only of rebellion against authority, it was also an attempt on the part of the artists to reclaim and recontextualize pre-existing genres.[4] [5] There were groups like the Flying Burrito Brothers who drew exclusively on country and western, or Fairport Convention that drew upon medieval music –in fact much of the sixties psychedelic scene revolved around a reappropriation of medieval style. However, the driving force behind the bands that had a serious, lasting impact across the board was the blues and R&B.

It would be unfair to say that bands like The Rolling Stones or The Yardbirds were not serious about their devotion to black American music, in fact the evidence to the contrary is overwhelming. It’s also not really feasible to say that a culture-distorting influence pushed this music onto them in the inescapable way that a culture-distorting influence today pushes rap music onto white youth. No, these bands had to seek out this source of otherness and authenticity. The fact that the rural nature of the American south was so foreign to the London-oriented sensibilities of these bands must have been a contributing factor. In one sense, the exotic nature that can be associated with what is thought to be “authentic” must be factored in, but I think we should not lose sight of the Faustian instinct. The physical reality of London was not enough for the artistic sensibility fomenting within it, as Spengler states:

It is as though the Faustian universe abhorred anything material and impenetrable. In things we suspect other worlds […] No other culture knows so many fables of treasures lying in mountains and pools, of secret subterranean realms, palaces, gardens, wherein other beings dwell. The whole substantiality of the visible world is denied by the Faustian Nature-feeling, for which in the end nothing is of earth and the only actual is space.[5] [6]

This indefatigable exploratory attitude, which Spengler locates at the center of western man, ought to orientate him towards exploration of the stars. But modernity can confound the best lain of teleologies: Tiki Torch Hawaiian culture, Southwestern art, chic east coast cosmopolitanism, etc., all of these cultural tropes await the Faustian man as he tries to aesthetically distance himself from his immediate reality. Hence, it’s no real surprise that Jimmy Page, Keith Richards, et al channeled their creative energies into a devotion for an artform that is both geographically and racially foreign.

This view is really the opposite of the conventional “white appropriation of indigenous music” trope. It falls in line with another type of conflation we need to consider: the conflation of authenticity with the idea of ownership or proprietorship. On this view, the genres that are adopted, or more pejoratively “appropriated,” are vocabularies or even languages. This conflation seems more apt than the prior two because it goes hand-in-hand with the linguist’s notion that languages and dialects are like peoples who are subject to life and death.[6] [7]

The blues is just a genre; it is no more mystical than any other genre and does not hold the promise of authenticity to the people who grew up in it and propagated it from within the culture that birthed it. Rural black and white Americans were on the lookout for new and more novel genres of musical expression, for them “the blues” was an established genre with established stylistic parameters, in a sense, these established parameters marked it as dead. American artists treated it as such and fused certain elements of the blues with other established genres like gospel, country and western, etc., and formed rock n’ roll. But it was the preservationist instinct of British musicians who treated the blues as a living organism that would transform the genre within new parameters and ultimately grant it the seal of authenticity we associate with it today. These artists essentially breathed new life into a dying language.

Music journalists and aficionados who try to chase down and deify the “raw spirit” of the blues in the name of a quest for authenticity are fundamentally misguided. They are so blinded by reverence for the racial other that they cannot grasp that the sense of authenticity that they associate with “the Blues” was already inherent to the artists who lead them to the genre in the first place. The British invasion codified the blues as authentic, transcendentally so, and without this disciplined and geographically foreign intervention the idea as such would not have existed.

Conclusion

Thinking of a genre in linguistic terms posits the idea that authenticity is inherently collectivist. Positing the idea that the dialect of a genre is transferable, insofar as it relates to art, is to posit it as being inherently artifactual. In opposition to this collective type of artifactual authenticity, however, there exists the strand of artifactual authenticity I hinted at earlier, this appears in the Neil Young chapter of Faking It, and I will refer to it as the individual, or Romantic, type of artifactual authenticity. Barker and Taylor describe Young’s approach to songwriting as an attempt to get past the critical aspect of the mind in order to experience a primal and unique source of inspiration. In the text this process is defined in terms of Romanticism and is exemplified by the work of Keats, Shelley and Coleridge. In my above defense of the British Invasion artists I see the blues as a principle, an outside source that spurs the imaginations of the individual artists who encounter it. Unlike the collectivist theory that posits this exterior force as a source of authenticity that governs the output of the influenced artists we ought to view these genres as cultural touchstones that prompt creative activity, not police it. This is not to deny that genres have aesthetic rules –they do for those who listen to and market the music being made. Instead this is a normative claim on behalf of artists, one that claims we ought to prioritize the generative aspect over the governing one.

This interpretation of authenticity accords with the three conceptual conflations that we have gone through so far: authenticity as honesty, authenticity as suffering and authenticity as ownership of a generic, dialect-like discourse. This conceptual flexibility coupled with the justifiable idea that authenticity’s enunciation only exists insofar as it is expressed in speech acts, or works of art seems to qualify it as a meta concept. This is a concept that is contingent upon conscious reflection, a reflection that we can qualify in objective terms. The aesthetic value offered by the attribution of authenticity to a work only exists insofar as it expresses this sense of objective distance between the work and its audience.

With this in mind, we have to step back and deem the view of western writers who see the music of foreign cultures as authentic solely because they are untainted by western self-criticism and self-assessment as chimerical because it is absurd to assert that native music had no technical or editorial aspects when, in fact, these aspects exist in the formal or ascertainable sense only after a particular style of music has been assimilated into the western system of genre classification. As we see with Taylor and Barker’s reference to Romanticism, even primitivism as a creative concept has been posited within the context of a specifically western frame of consciousness.

I believe that the different conceptual conflations I have offered in this essay tell us particular things about how we think of authenticity and for that reason are of a certain value. This latest variation on the theme: the conflation of authenticity with primitivism, which is a thread that has run throughout the entire essay, is of a higher caliber than the other conflations and is therefore harder to analyze away. The desire to tap into the spirit of authenticity in its primal state, regardless as to whether this authenticity is sought within our own culture or in another seems to be something that we as whites have carried with us since we began documenting our thoughts and histories. It is probably the most useful, i.e., generative conflation, and it originated exclusively within European cultures. This devotion to the primitive nature of authentic expression has endured scholastic practices that have sought to regulate and discipline its modes of expression, nevertheless, when this authenticity is perceived in a work of art it affects us on our most primal level of being.

It is appropriate that the chapter, which focuses on what I have called the generative aspect of artifactual authenticity, is about Neil Young, an artist who had never expressed total fidelity to any one genre.

For writers, composers, and artists must always function on two levels: as creators on the one hand and as self-critics, editors, or mediators on the other. When one attempts to separate those two interlinked levels of thought –to allow only the first to function fully and to suppress the second- that’s when one can feel as though one is writing “as naturally as the leaves to a tree,” that’s when one can channel the imagination most fully, and that’s when writing can become a “release” rather than a “craft.” Young, like Keats, is trying to capture the innocent imagination of a child. This is essentially a quixotic goal –one can never achieve the state of pure naturalness that romantics aspire to- yet the attempt to reach that goal can have profound consequences for one’s art.[7] [8]

At the beginning of this essay I referred to Alex Chilton as an “interpreter” of R&B and soul music. This is a description that I wrote without any thought or consideration, but it is a telling choice of words insofar as it points to the idea that recreating genres or even basic units of genres, i.e., songs is akin to a linguistic act. The fact that Chilton performed the song in a stripped down and loose way is not because he viewed the blues as a raw source of primitivism, it is merely the result of this particular song’s performance conforming to his personal aesthetic at the time, an aesthetic which was intended to eschew pretension. When source material is filtered in this way the artist is inserting himself into the mythos of the genre in the way that Eliade claimed that individuals identified themselves with the characters from their communal myths. Chilton of course played the song through the prism of the British musicians who played it before him, but he also played it as a son of Memphis who knows and identifies with the sentiment of the song. He plays it as merely a song, and it therefore stands as one among many others.

Notes

[1] [9] It can be argued that the concepts of the former ascertainment are just as grand and ambiguous insofar as they involve Truth and Respect. This may be true and I will grant it a certain qualitative victory, however, it is worth pointing out that if this qualitative analysis deems both types of authenticity to be equal there is still a quantitative analysis that would surely come down on the side of the historical idea of authenticity I am emphasizing here.

[2] [10] Faking It by Hugh Barker and Yuval Taylor (2007). W.W Norton and Company, Inc. New York. p. 10

[3] [11] This is the form of liberalism that denies the ethnic component of a community in order to instigate racial equality, it is not to be confused with radicalism (a trait prevalent in the sixties) that did not deny the ethnic component and instead celebrated the heterogeneity of racial intrusion into culturally white spaces. I am ignoring this radical strand of blues appreciation –if such a thing exists- because it seems to value black music solely as a means to antagonize the white community.

[4] [12] It is worth noting that the nineties were similar in this respect.

[5] [13] The Decline of the West, An Abridged Edition by Oswald Spengler (2006). Vintage Books, a division of Random House. New York. p. 204

[6] [14] In addition, this biological cycle of birth, growth, decline and death conforms to Spengler’s basic view of civilizations being biological entities that follow the same pattern: “Each Culture has its own new possibilities of self-expression which arise, ripen, decay and never return.” (Ibid, p.17)

[7] [15] Faking It by Hugh Barker and Yuval Taylor (2007). W.W Norton and Company, Inc. New York. p. 213