Ilya Glazunov: An Obituary

Posted By David Yorkshire On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledIlya Glazunov is not a name that is widely known in Western Europe, to the point where his passing went largely unnoticed on the 9th July of last year. I personally only found out at the end of the year, and have only just managed to find the time to write this obituary, involved as I am in a number of cultural projects that will bear fruit in the near future. Born into a Russian noble family in St. Petersburg, known at that time as Leningrad in the Soviet Union, he lost his parents to starvation in the siege of that city during the Second World War, he himself being one of the few survivors from his family. While studying at the Repin Institute of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, he considered entering the clergy at a time when the Soviet state still persecuted Christians, although at a lesser level than during the early phase of the regime. A priest persuaded him to “Go, learn, and fight for truth.”

His love for the Orthodox Church never left him, though, and was a constant influence on his painting, both in terms of subject matter and style. His style is certainly reminiscent of mediaeval East European icon painting and marks a conscious departure from the style of Soviet Realism favored by the state. Glazunov obviously sees the Orthodox Church as an important part of Russia’s identity, and as a remnant of its monarchical past that he also venerates, and as an organic part of the life of the peasantry. This led him to champion the Orthodox Church as Communism waned. Indeed, one readily sees his critique of Communism as destructive of both Church and peasantry in his painting Dispossession of the Kulaks (below), painted after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

Even during the Soviet period, Glazunov courted controversy by pushing the boundaries of what was deemed acceptable by the authorities, his 1964 exhibition being closed down and his painting The Roads of War, that showed a Soviet retreat during the Second World War, later burned. His Mystery of the Twentieth Century (below) also had to be hidden until Perestroika because of depictions of Jesus and Tsar Nicholas II, with copies leaked to Western magazines in the late 1970s.

Glazunov’s rejection of Soviet Realism did little to diminish his reputation, though. He also enjoyed special privileges, such as freedom of travel outside of the Eastern Bloc, painting the portraits of dignitaries and others all over the world. His subjects included politicians and celebrities, which, along with his book illustrations of Russian writers, particularly Dostoyevsky, provided his bread and butter. He was allowed to travel because the Soviet leadership had met to discuss whether to actually exile him, yet his loyalty to Russia was never in question and his honesty often admired, such as when he was asked to portray the happiness of the Ryazan laborers, but found them anything but and instead represented them as they were, which initially brought him criticism, but then praise after a governmental investigation into both conditions and productivity there that vindicated him. He was hailed as an artist sensitive to the worker’s struggle.

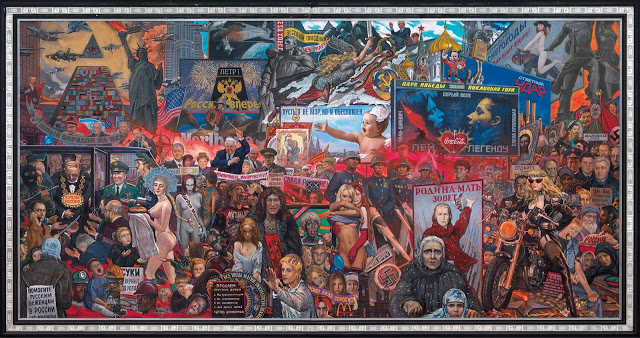

Staunchly anti-democratic and anti-capitalist, Glazunov shared some of the ideals of Communism, as it is often forgotten that the aristocratic Right detests liberal capitalism as much as the Communist extreme Left. His greatest critique of the free market, The Market of Our Democracy (above), was painted in 1999, however, long after the collapse of Communism. The painting would have certainly gone against state censorship on grounds of good taste, yet was perhaps more relevant at the dawn of the new millennium in any case, as Russia began to question liberal decadence and move towards the nationalism that would see Vladimir Putin elected the following year. The picture shows many Rightist critiques of liberalism: the promotion of sexual promiscuity, pornography, and homosexuality, abject materialism, and the gulf between rich and poor. And over on the left side (where else?), a Jew is to be found with a gold chain of Stars of David, bearing a sign hanging around his neck with the legend, “I shall purchase Russia.” Such honesty has earned Glazunov a reputation as an anti-Semite.

Yet a large body of his work is dedicated to the celebration of Russia’s rich history, rather than critique. His cycle The Kulikovo Field was started in the 1970s and ran well into the 2000s, which depicts the pivotal battle against the Mongol Golden Horde and Tatar army by the allied principalities that would go on to form a unified Russian state. It is thus the moment in history in which the modern state of Russia was born. Above is Sergius of Radonezh and Andrei Rublev, the latter having been newly canonized when the painting was begun as one of the greatest Russian iconographers. Sergius is one of the most venerated saints in the Orthodox Church, and blessed Russian hero Prince Dmitry Donskoy before he went into battle against the Mongols and Tatars. He also sent the warrior-monk champion Alexander Peresvet, who battled the Mongol champion Chelubey, which Glazunov immortalizes in The Duel (below).

Both parties were killed in the duel, although Peresvet apparently stayed in the saddle, whereas Chelubey fell. What is interesting in the painting is that the horses bear the real nature of the battle–the struggle for racial dominance–in their colors, in which the white horse with the blond mane of Peresvet is shown to have the upper hand.

The Mongols and Tatars are highlighted as both racially Other and thus culturally barbarous. Temporary Superiority of the Tatars (above) shows a Tatar having beheaded a blond North European warrior, which reminds us of the practices of modern Muslims from the barbarous races. The leader of the Golden Horde, Khan Mamai (below), is seen as more demon than man, his face lit up seemingly by hellfire and his eyes burning with relentless wanton and unrestrained cruelty.

In contrast, the Russians are always of the Nordic type, blue-eyed and noble of countenance, steely-eyed, yet unconsumed by their passions, as in Eve, Before the Battle of Kulikovo (below). Glazunov no doubt also attributes this to the Orthodox Church, which is ever-present alongside the soldiery, giving us the distinct impression that the Battle of Kulikovo is part of a racial holy war.

Nor does Glazunov forget the noble woman. Like his male figures, there is an assuredness in Princess Eudoxia’s blue eyes and equally a serenity. Dmitry Donskoy’s wife, portrayed in Princess Eudoxia in the Temple (below), was no mere bauble, and established the Ascension Convent in Moscow. Neither is her feminine beauty neglected, showing strength in femininity that puts feminism to shame.

[11]

[11]Yet for all his veneration of the Orthodox Church, Glazunov does not neglect Russia’s Pagan past and the Varangians that founded the Kievian Rus’ from which Russia takes its name. Grandsons of Gostomysl: Rurik, Truvor, Sineus memorializes the Viking heritage of many of Russia’s noblemen, which one sees in Glazunov’s racial foregrounding. Ilya Glazunov shows us time and again that the strength of our ancestors is important when going forward into the future, but that this must be renewed in contemporary artwork that gives them relevance to the contemporary age. Glazunov’s campaigns saved many of the old buildings in Moscow from brutalist redevelopers, and thus the Muscovites from the banal depression of meaningless concrete. It is why Russia is fast becoming a world powerhouse built upon a nationalism that, while currently civic, may quickly turn ethnic as such art as Glazunov’s seeps into the racial consciousness. Ilya Glazunov may now be dead and buried, yet he has also become as immortal as his heroic figures. Let us follow his example.

This article originally appeared at the Mjolnir Magazine [13] Website on February 24, 2018 [14].