For Europe:

Hungary’s 2018 National Election

Posted By

John Morgan

On

In

Counter-Currents Radio,North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

[1]

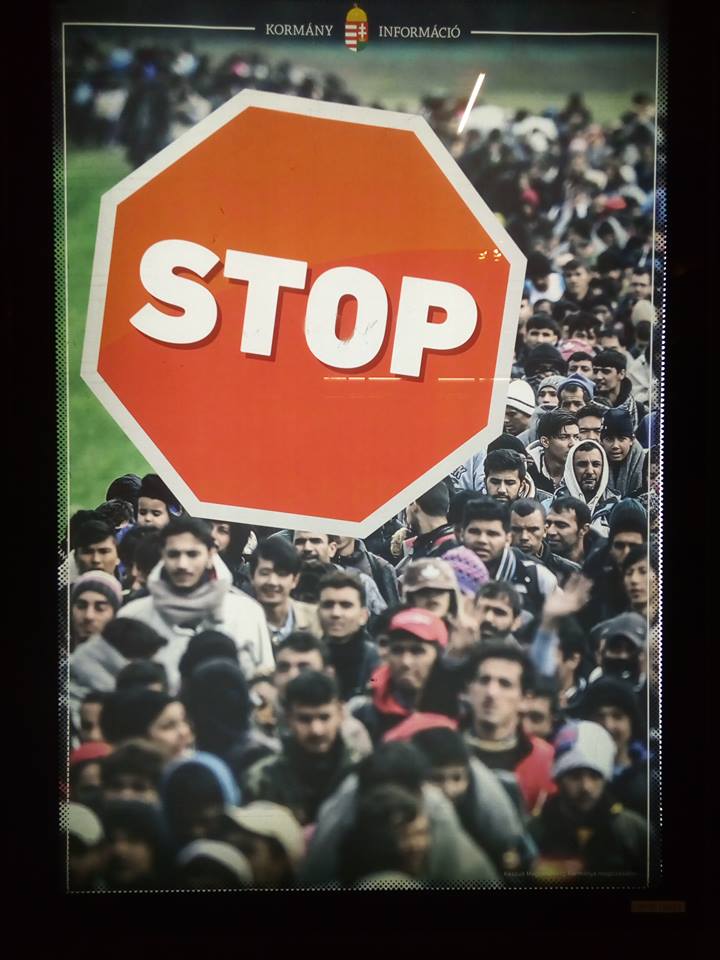

[1]Fidesz-sponsored billboards that were up all over Budapest recently, showing the major opposition figures. The phrase reads, “They want to break the border.”

5,038 words

Audio version: To listen in a player, use the one above or click here [2]. To download the mp3, right-click here [2] and choose “save link as” or “save target as.” To subscribe to the CC podcast RSS feed, click here [3].

Hungary in 2018 lies under a pall of darkness. Its citizens, kept in thrall by being fed a steady diet of fear of imaginary threats, unbridled racism, and cynical hatemongering through the government’s relentless propaganda, are cowed and starving, but dare not speak out, as the government brutally cracks down on the slightest dissent. Alternatives to the official narrative are smothered. Hopelessness and despair are rampant. A small handful of resistors, supported with funds provided by noble and selfless oligarchs, are waging a desperate battle to overthrow the oppressive regime and put Hungary back in the hands of the wise men and women of Brussels, who want nothing but to guide the country away from dictatorship and further towards the utopia the European Union wants to grace it with, in its infinite benevolence.

Just kidding. Hungary in 2018 is actually a very pleasant place. But this is the view of Hungary that is being advanced by all of the figures and parties who oppose the inevitable reelection of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his party, Fidesz, for a third consecutive term in the national election on Sunday, and which they want their constituents to believe. Short of an unprecedented upset, however, all of the major polls indicate that Fidesz will comfortably retain its parliamentary majority, the only question being if it will manage to attain a supermajority (two-thirds), which is required in order for the constitution to be amended. It’s unlikely that Fidesz will achieve this level of success, although this doesn’t pose any serious challenge to their governance considering that Fidesz has already made all of the constitutional changes that it sought since returning to power in 2010.

Fidesz doesn’t enjoy this level of support because Orbán and his party are uncritically admired by a large number of Hungarians – that is most definitely not the case – but primarily due to two factors: Orbán’s personal charisma, and the failure of any of their opposition to present a more compelling alternative.

Fidesz’s most serious opposition, as it was in the last two elections as well, comes from Jobbik. Jobbik has largely abandoned the Right-wing rhetoric for which it was once justifiably renowned by Rightists not only in Hungary, but throughout the Western world (including by me), and has instead reinvented itself as little more than a catch-all party for everybody of all persuasions who hates Orbán.

Shortly after the last national election in 2014, in which Jobbik managed to garner twenty percent of the votes cast, I had the opportunity to speak with Márton Gyöngyösi, Jobbik’s International Secretary. He said that Jobbik’s task was to find a way to appeal to Budapest voters. Hungary has a population of ten million; of those, two million live in Budapest, so electoral success there is crucial. The problem is that, while most of Hungary remains staunchly conservative, like voters in most large urban centers, Budapest voters tend to lean very much towards the Left. It seems that Jobbik’s strategy since then has been to try to remake itself so as to become a viable option for liberals.

To be sure, Jobbik was placed in a difficult situation. For roughly a year between the election in 2014 and mid-2015, the momentum very much seemed to be theirs, and people began to talk of it as a serious contender for displacing Fidesz. However, beginning in the summer of 2015, the national conversation in Hungary, as throughout the entire European Union, came to be dominated by the migrant crisis. Orbán successfully took the lead, both by introducing stringent measures to prevent migrants from entering the country as well as by opposing Brussels’ attempts to impose migrant quotas on the country, and in so doing he managed to win back the initiative. Jobbik, as a Right-wing party also opposed to mass immigration, was left in the rather unenviable situation of being able to do little more than lend their support to Fidesz’s initiatives. As such, they had to find other ways to distinguish themselves.

Jobbik decided to focus its efforts on discrediting Orbán and Fidesz by adopting the rhetoric that the Left had already been using, albeit less successfully, focusing primarily on making accusations that Fidesz is corrupt and that it has been engaged in undermining democracy. The past year has seen a “war of billboards” ongoing in Budapest, with public kiosks frequently being used by either Fidesz or Jobbik to snipe at each other. Last summer, Jobbik funded a billboard campaign featuring pictures of Orbán and some of his top people beneath slogans such as “Mr. Orbán, how did your friends get rich?” and “You work, they steal.”

It cannot be denied that Jobbik has enjoyed some considerable success with this strategy; I have seen for myself that many Hungarian liberals who never would have given Jobbik the time of day four years ago are now speaking of their intention to vote for them this time around. Hungary’s Leftist magazines have been featuring articles about whether it’s justifiable to ignore Jobbik’s past in order to support them as the party with the best chance of unseating Fidesz – the consensus seems to be that yes, it is.

Diehard Jobbik supporters insist that the party’s core principles remain the same, and that it’s only their image and strategy that has changed. This seems to be a similar type of argument as the Trump 4-D chess canard: It’s all just window-dressing, and as soon as Jobbik comes to power, they’ll tear the mask off and revert to their old ways (and presumably alienate many of the liberals who now constitute much of their base).

Although diehard Jobbik supporters are somewhat difficult to find today, in any event; many of Jobbik’s old leadership have either been dismissed or have resigned in frustration since Jobbik embarked on its self-renovation (the Hungarian press refers to it as the “candy campaign,” their attempt to soften their image from the highly militant one they presented in 2010), and its old members have deserted the party in droves, either becoming Fidesz supporters or joining one of the marginal extreme Right-wing parties. But their old supporters have been replaced by a new breed. I’ve seen Jobbik poll as highly as nineteen percent in recent weeks, which if accurate means they are only faring slightly worse than they did in 2014. We’ll have to see how things shake out on Sunday, but most likely Jobbik will hold on to its place as the second-largest party, even if it now represents a very different body of voters.

My own view of Jobbik is that we can only judge parties and politicians by what they say and do, and what Jobbik has been saying and doing recently has been troubling. Last year, Fidesz passed legislation which attempted to force the George Soros-funded Central European University (CEU) in Budapest – unsurprisingly, a conduit for American-derived neoliberal values and hostility to the Fidesz government – to conform to the standards which are expected of all universities in Hungary, a move which was decried by the University’s supporters as an attempt to force it to shut down. Jobbik’s MPs voted unanimously for the legislation to be subjected to judicial review, with Jobbik’s Chairman, Gábor Vona, saying that it was their duty to stand up to the Fidesz “dictatorship,” even if Jobbik was not necessarily defending CEU as an institution. This was seen by many Hungarian Rightists as Jobbik showing that it was willing to side with Soros and his minions if they thought doing so would curry favor with liberals.

There have been other alarming indicators as well. Jobbik used to be staunchly opposed to Budapest’s Gay Pride parade; more recently, Vona has said that he is unsure that he still feels this way about it, and has said that homosexuals can “be proud of who they are.” Jobbik also used to be known for its willingness to discuss the negative impact of Jewish interest groups on Hungary; in 2016, he sent Hanukkah greetings to Hungary’s Jewish leaders (amusingly, these were rejected), and in November, Vona spent an evening at the Spinoza Theater, a well-known meeting place for Jewish intellectuals, to address an audience and attempt to prove that he wasn’t really a Nazi after all. Similarly, Jobbik used to be vocally euroskeptical; these days, given that Orbán has been making a name for himself in this regard, they are saying that this is something that merely needs to be “evaluated.”

Perhaps this is indeed all some 4-D chess game; however, it seems more likely to me that Jobbik merely loves power more than it loves the principles it was founded upon. As a result, Jobbik can only nowadays be seen as – at best – a liberal conservative party. They and Fidesz have swapped places; ironically, now Fidesz is the closest thing Hungary has to a “radical” Right-wing party.

Some also find Jobbik’s fixation on the “corruption” theme against Fidesz to be somewhat ironic given that Jobbik’s biggest financial backer these days is the oligarch Lajos Simicska, who was a founding member of Fidesz and a personal friend of Orbán’s until they had a falling out for unknown reasons in 2015, leading to him defecting to Jobbik.

Vona has declared publicly that if Jobbik loses the election (and they will), that he will step down as Chairman. Who will succeed him is unclear, but many think that it may be László Toroczkai, the Mayor of Ásotthalom, a small town on the border with Serbia. Toroczkai was the first to spearhead the idea of the border fence that closed off the route that the migrants were using to enter Hungary, and in 2016 he became part of Jobbik’s top leadership. Toroczkai is still viewed with respect by many on the Hungarian Right, and has distanced himself from some of Jobbik’s recent problematic statements; as such, were he to become leader, it’s possible that he might try to move Jobbik back in a more genuinely Right-wing direction – assuming Jobbik can be salvaged at all, at this point. Some predict that it might just fall apart entirely. Fidesz is certainly not underestimating Jobbik’s potential: In December, after charging Jobbik with “illegal campaign financing” due to bookkeeping errors, the government issued a fine of more than two million euros against the party, more than was in its coffers at the time, although it was agreed that the fine would not have to be paid until after the election. This was seen by many as an insurance policy taken out by Fidesz against the possibility of Jobbik’s success, as their main rival.

Whether it is a renewed Jobbik or a new party, it is my fervent hope that some staunchly Rightist force will emerge to fill the vacuum, as the relationship that Jobbik had with Fidesz previously – being the “extremists” that would constantly force the more center-Right Fidesz to adjust its ideas, pulling them further towards the Right than they might otherwise have been in a field where they were the only significant Right-wing force – was an extremely constructive one, and Hungary, which tends strongly towards the Right anyway, badly needs such an entity.

The other major opposition parties are all various stripes of liberals. There is the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP), which emerged in 1989 out of the Communist party that had ruled Hungary during the Soviet period, and which is similar to the sort of neoliberal “socialist” parties one finds in Western Europe, combining a love for globalization and the free market with libertine values. They have held power for three terms since then, most notably from 2002 until 2010. The MSZP’s last term in power went rather badly, when a recording of a secret speech to the party leadership made by the then Prime Minister, Ferenc Gyurcsány, was leaked to the press in 2006. In it, he admitted that the party had lied about the country’s economic status, as it actually was hovering near bankruptcy (in 2008 it became the first EU member state to require a bailout), and had covered up their lack of any accomplishments of note in order to win reelection. When this recording hit the airwaves, it led to an uprising of nationalists in Budapest in September and October. There was widespread rioting and street fighting throughout the city, and this energized both Fidesz and the fledgling Jobbik party. As a result of this scandal, Fidesz handily defeated the MSZP in 2010, and has remained in office ever since. The MSZP remains widely discredited in the eyes of Hungarians, and few see it as a serious contender for power at present.

Not to be so easily beaten, however, Gyurcsány went on to form a new party of his own, the Democratic Coalition (DK), which has managed to establish itself as a minority presence in Parliament. The DK’s declared intent is to provide a more “democratic” alternative to the MSZP and to represent Western European-style liberalism, and is strongly pro-EU. Like the MSZP, however, the DK holds little hope beyond hanging on to a few seats in Parliament.

The other major Leftist party is the Politics Can Be Different Party (LMP), led by Bernadett Szél, and which is Hungary’s Green party. In addition to the usual Green concerns with the environment and sustainable development, the LMP has also focused on the plight of Hungary’s poor, which is an important issue in a country that is still rife with poverty and where there is a significant homeless population. While they disagree with the liberal elements of its rhetoric, some Hungarian Rightists have told me that they do respect the LMP for being seriously committed to its values and for addressing some problems that the other parties won’t discuss.

Independently, none of these parties can be considered as seriously threatening Fidesz’s hold on power in the upcoming election. The one ray of hope for the opposition came in the form of a Fidesz candidate who was defeated by an independent candidate, Peter Marki-Zay, in a mayoral election in the city of Hódmezővásárhely in February. Some have taken this as an indication that Fidesz can be beaten, although others have warned against reading too much into it, pointing out that local elections are often determined by forces very different than those that act on the national level. Moreover, it seems that Fidesz expected to lose the election.

This hasn’t stopped Marki-Zay from milking his success for all it’s worth in the weeks since his victory, casting himself as a leading light of the anti-Orbán opposition. In a recent interview [4], he claimed that if the four major opposition parties obtain enough parliamentary seats between them, they can then form a technocratic coalition designed to wrest power from Fidesz and, as he put it, restore the “state of law” and “democracy,” and “reaffirm Hungary’s commitment to European (meaning the EU’s) values.” This is overly optimistic, however, since it seems unlikely that, even combined, the four parties will get enough votes to overturn Fidesz’s simple majority, and in the event that they did, it’s far from certain that they would be able to put aside their differences and form a unified bloc. Marki-Zay insisted that this can happen for the simple reason that these parties will be forced to work together for their own survival. Nevertheless, it remains a long shot.

It should be noted that none of the major opposition parties has dared to challenge the government’s stance on border protection and the migrants; that would be political suicide in Hungary. Nevertheless, all of these groups have been speaking of the need to “increase European cooperation,” by which they mean mending Hungary’s fences with the EU. Whether this is their intent or not, cozying up to Brussels implicitly means accepting their stance on mass immigration and thus undoing what Orbán has achieved.

As for Fidesz itself, they have banked everything in this election on the migration issue. Since 2015, all of the party’s rhetoric has been focused on the threat posed by the migrant crisis, Brussels’ attempts to force Hungary to take in migrants, and in depicting George Soros and his organizations as the biggest danger Hungary faces today. Indeed, the government has launched numerous billboard campaigns against Soros personally over the past year, including one featuring a photo of Soros laughing above the words, “Soros, we are the ones who will laugh last!” This has been more than just rhetoric: for the past year, the government has been drafting legislation targeting the Soros-funded institutions in Hungary, one of the most notable recent examples being a suggestion that organizations which support the entry of migrants into Hungary should be fined in order to help fund border security.

[5]

[5]Government-sponsored billboards that were up all over Hungary last summer. “Soros, we will be the ones who laugh last!”

This conflict with Soros is somewhat ironic in light of the fact that Fidesz and Orbán themselves were supported and funded by Soros’ foundations in the late 1980s and early 1990s. This has given rise to some conspiracy theories which claim that they are controlled opposition. If we admit the fact that politicians and parties can sometimes have genuine changes of heart with greater experience and under changing circumstances, however, I think we can safely disregard these rumors. It’s difficult to imagine what end Soros would be pursuing if there is some sort of secret collusion going on.

Related to this, it is interesting to note that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu paid an official state visit to Hungary last July – the first Israeli leader to do so since the end of Communism. The ostensible reason for his trip was to discuss cultural initiatives and trade relations, but the timing of his visit, coming in the midst of the government’s conflict with Soros, was widely interpreted as indicating Netanyahu’s tacit endorsement of Hungary’s side in the war. And indeed, Netanyahu himself has been critical of Soros on numerous separate occasions. Fidesz itself must be seen as a “kosher conservative” party – while many liberal critics have accused the party of using thinly-veiled anti-Semitic rhetoric, particularly in relation to the anti-Soros campaign, the fact is that Orthodox Jews are some of their biggest financial backers. This is easily understood when one realizes that it is not to the advantage of Jews for large numbers of Muslims to end up in Europe, and the Orthodox, being perhaps more sensible than their neoliberal co-religionists, seem to have figured this out. Viewed pragmatically, this relationship can be easily understood, but it is something that should be noted.

Viktor Orbán certainly deserves a great deal of praise, and he is the closest to a “true Right” figure that one can find among national leaders within the European Union today. He acted swiftly, decisively, and effectively to put an end to the inflow of migrants into Hungary in 2015. Since then, he has made himself the chief spokesman for opposition to Brussels over the issue of migrant quotas – fortunately, Hungary has been joined by several other nations in this (primarily the other nations of the Visegrád Group – Czechia, Poland, and Slovakia, and now with the new Austrian government appearing to consider joining their ranks), but Orbán has most definitely taken the lead in this matter. His government has made a point of making use of the sorts of rhetoric that are condemned as “extremist” in the West, talking of white genocide [6], the preservation of Christian values, the incompatibility of large numbers of immigrants from non-Western origins with Europe as we know it, and so on. To take an example from one of his masterful speeches, of which there are many, was his recent address on March 15 [7], in which he said:

I know that this battle is difficult for everyone. I understand if some of us are also afraid. This is understandable, because we must fight against an opponent which is different from us. Their faces are not visible, but are hidden from view; they do not fight directly, but by stealth; they are not honorable, but unprincipled; they are not national, but international; they do not believe in work, but speculate with money; they have no homeland, but feel that the whole world is theirs. They are not generous, but vengeful, and always attack the heart – especially if it is red, white, and green.

Is there anything in this with which we could disagree?

Fidesz also held a referendum in October 2016 on the question of whether or not Hungary should accept EU migrant quotas – the answer was a resounding “no” – in order to show Brussels that the Hungarian people were behind them and enable the rejection of this imposition to be written into law. Orbán has carried out other praiseworthy actions as well, including taking steps to limit and monitor the activities of foreign NGOs operating in Hungary, and paying off Hungary’s debt to the IMF early in 2013, a debt which had been incurred by the previous socialist administration when it required a bailout to keep the national economy afloat. Orbán achieved this in order to get out from under the IMF’s thumb by levying special taxes on multinational corporations to protect domestic businesses. And in 2016, he evicted Uber from the country at the behest of the nation’s taxi drivers.

Regardless, however, one must take a nuanced view of Fidesz and Orbán. They should not be seen as ideologically committed Rightists. Orbán is a quintessential populist; he is acting as the opposition on the migrant issue because he knows that this is a popular viewpoint among Hungarians, who, due to their troublesome history of being constantly invaded and their inherently conservative nature, as well as their strong sense of their own identity, tend to be both proud and suspicious of strangers. While Orbán should be praised for his handling of the migrant crisis, the fact remains that the government initially reacted passively to it. When the migrants began flowing through Hungary along the Balkan route in 2014 and early 2015, their initial view, akin to that of Greece, Serbia, and other countries, was that it was really a Western European problem given that the migrants had no intention of staying in Hungary, but wanted to move on to places like Germany and Sweden, where the state-supported social benefits were calling to them. It was only when the aforementioned László Toroczkai began posting photos and videos of the armies of migrants who were crossing his town daily, and the impact they were having upon it, on social media, and word about it began to spread, that the government felt goaded into action. Fortunately, Orbán and his strategists soon realized that this was a way to distinguish themselves, and the rest is history. But it should not be forgotten that they had to be embarrassed into doing what was right.

Similarly, while there are many terrific things about Hungary, and I admire the government’s ability to maintain it as a beacon of the “real Europe” in the face of so much pressure and opposition, one should not overlook Fidesz’s negatives. Foreigners tend to judge a country’s politics by its foreign policies, which is why so many people on the Right in other countries, desperate for a hero, see Orbán as a shining example. But people judge their own country’s governments primarily by its domestic policies. Even my Hungarian Rightist friends who support Fidesz on the migrant question and in its conflict with Soros often claim that they make use of these things as a smokescreen to deflect from those issues that they haven’t been doing anything about. One is poverty, which remains widespread throughout the country – the average Hungarian salary is the equivalent of about four hundred US dollars per month, and the taxation rate can range up to fifty percent. And Budapest’s metro stations are filled with the homeless. Another is the state of the public health system, which is sub-par. And then there is the brain drain. Of a nation of ten million people, approximately 800,000 are currently working abroad – and this of course constitutes many of their best workers. One of my friends explained to me once that, no matter how much you love your country, it’s difficult to make yourself remain when you can make more working at a McDonald’s in England as you can as a doctor in Hungary. Sadly, this is not much of an exaggeration, and yet the government has done nothing to offer incentives to highly-skilled workers to stay. A disturbing recent survey [8] found that nearly half of young Hungarians would leave the country if they could – primarily in pursuit of higher wages. Perhaps one should not be too hard on Fidesz, given that the country was nearly bankrupt when they took power in 2010 – but nevertheless, many Hungarians feel that they have not done enough to address these issues.

But the most frequent charges made against Fidesz by its opponents are that it is corrupt, and that it is undemocratic. No actual court cases have ever been brought that prove that the former is so – the opposition, of course, claims that this is because the judiciary is run by Fidesz. It is true that there have been odd cases of friends of Orbán’s who have received lucrative construction contracts and the like, and that many of his aides have gotten rich in recent years – but whether this is actually evidence of corruption, or just an outcome of the usual political nepotism remains unclear. The fact is that of the four main opposition parties, three remain untested in office, so it is far from certain that, even if any of them could wrest power from Fidesz, they would fare better in this regard. And as for the fourth, the MSZP, they were evicted from office precisely for corruption and lying to the public.

The charge of suppressing democracy usually rests on the fact that, when Fidesz came to power in 2010, they quickly set about securing their own channels in the mass media at both the national and local levels. It cannot be argued that a large portion of the Hungarian media is dominated by Fidesz. Nevertheless, there are other channels – Hír TV, funded by Orbán’s rival, Simicska, being chief among them, and which conveys a strongly anti-government line. Some complain that many Hungarians have no access to non-Fidesz points of view; I don’t see how this is possible, given that freedom of speech remains a protected right in Hungary, the Internet is unregulated, and that there are most definitely publications and TV channels which criticize the government on a regular basis. How much is too little? It seems difficult to say. In any event, anyone who has actually spent time in Hungary would laugh at the idea that it is a “dictatorship,” when hardly a week goes by that there isn’t some sort of anti-government protest in Budapest.

In the end, while I would urge those of you reading this not to see Fidesz and Orbán as heroic figures above criticism, or as symbols of purity, I believe that they are certainly the best option available to the Hungarian people at the moment. More than this, Orbán has become a vital inspiration to anti-immigration movements throughout the West, and it can be hoped – perhaps naïvely – that their approach to the issue might eventually begin to effect real change on the matter in Brussels and throughout Western Europe. Orbán and Fidesz have been tested and have shown that they can achieve results when it comes to the migrant crisis and in standing up to the EU. Indeed, they seem to be laying the groundwork for something that might someday end up becoming an illiberal alternative to the EU – something that is desperately needed, if Central and Eastern Europe are to get out from under Brussels’ thumb and avoid the problems that have been plaguing Western Europe, perhaps fatally. It is to be hoped that in their next term they will make more of an effort to address the sorts of problems I mentioned above, and thus become a true government of the people, and not restrict their achievements to the international stage. By the same token, if the dam against the migrants were to break, all of these other issues would become irrelevant – since Hungary would no longer be a country for Hungarians. So it must be said that, in the end, Orbán is at least standing firm on the most fundamental issue.

A couple of weeks ago, I spent a morning at one of Budapest’s famous thermal baths with a friend who was visiting from out of town, and we happened to be approached by a ‘56er – a man who had been a resistance fighter against the Soviets in 1956, had been forced to flee to the United Kingdom, where he spent the next few decades, and who then finally returned to Hungary in his old age. He asked me if I understood why so many young people in Budapest are opposed to Orbán. I speculated that it was simply because they see the success of the West as reflected in films and TV programs, and believe that this success follows from the neoliberal values that the West itself purports are what make it great. He shook his head and said, “They just don’t know what things were like before! If they did, they would understand why Orbán is so important. The history of Hungary is filled with the tragedies of invasions. We don’t need another one.” In the end, this is the truth: Orbán, for all his flaws, is needed because he wants to preserve Hungary as it is, not as the politicians in Brussels and Washington would like it to be.

Hungary’s election this year is not simply a matter of national politics; it will also help to determine the fate of all of Europe as well. For the future of both Hungary and Europe, here’s to four more years for Viktor Orbán!