Too Much Victory?

The Hungarian Election Results

Posted By

John Morgan

On

In

Counter-Currents Radio,North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

1,478 words

Czech version here [2]

Audio version: To listen in a player, use the one above or click here [3]. To download the mp3, right-click here [3] and choose “save link as” or “save target as.” To subscribe to the CC podcast RSS feed, click here [4].

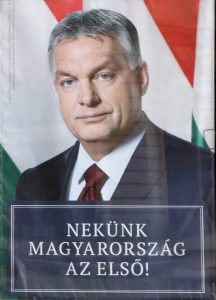

Defying predictions that a more energized opposition would reduce the parliamentary majority of Viktor Orbán’s party, Fidesz, in Sunday’s national election, their result is projected to be identical to what it was in 2014, with over 98% of the votes counted as of this writing: 66.83% of the Parliament (133 seats). This means that not only did Fidesz retain its majority, which was expected, but they even managed to hold on to their two-thirds majority, which means they can continue to make modifications to the national Constitution without having to cooperate with other parties, giving them a monopoly on political power at the national level. There is certainly a great deal of hand-wringing going on in Brussels, Washington, and in the rootless offices of George Soros’ various organizations today.

While this led to jubilation among Orbán’s supporters, it was a heavy blow to the opposition, which had seemed to be much more strongly mobilized this time around, falling for their own rhetoric that popular dissatisfaction with Fidesz across the country was growing. Their hopes seemed to be confirmed by the fact that voter turnout was over 68%, higher than any other national election in more than a decade. Reports throughout the day suggested that voters frustrated with Orbán were coming out in greater force than previously, and late in the day even Fidesz’s own spokesmen were conceding that they had most likely lost their supermajority. In retrospect, however, it seems that while the liberal opposition in the urban centers did indeed turn out in greater numbers, this was counteracted by a greater turnout among conservatives in the countryside, perhaps concerned over the possibility that Fidesz might be weakened. As it turned out, not only did the opposition fail to displace Fidesz, which was widely assumed anyway, but they failed in their more modest goal of ending Fidesz’s supermajority, and in fact they did not reduce Fidesz’s power by one iota.

Once again, as it also had done in 2010 and 2014, Jobbik emerged as the top opposition party, as anticipated by observers. Having moved away from its radical Right roots and reinvented itself [5] as a liberal conservative party since the last election, their strategy seems to have garnered some small degree of success, for in spite of the fact that they have alienated or distanced themselves from many who formed their previous base, they did manage to slightly increase their parliamentary presence, winning 13.07%, or 26 parliamentary seats – in 2014 they won 11.56%, and 23 seats.

Nevertheless, this came as a disappointment not only to Jobbik but to many of their new, more liberal supporters who saw them as the best chance of unseating, or at least reducing, Orbán’s lock on power, in spite of their distaste for Jobbik’s past rhetoric. Whether Jobbik’s new strategy of outreach to liberal voters, and effectively swapping their traditional base for a new (and alarming, from a Right-wing standpoint) one, was really successful with a gain of only three seats remains debatable, although they did at least hold their ground.

Jobbik’s leader, Gábor Vona, had announced during the campaign that if Jobbik failed to obtain a majority, he would resign as Chairman, and he did indeed announce his resignation at his concession speech on Sunday night. It is still possible that he might be re-nominated when his party meets to choose a new leader, but that remains to be seen. Also to be seen is whether Jobbik will continue along the line it has been following in recent years of presenting itself as little more than the “anyone but Orbán” party, or whether they will perhaps try to resume a more genuinely Right-wing program. The latter is fervently to be hoped for, albeit they hopefully will be able to do so enriched by the wisdom garnered by their new approach, and continue to find ways to appeal to more than just Rightist voters. They are certainly still in a better position than anyone else to mount a challenge to Fidesz; the only question is whether they will be able to seize and build on what they have accomplished by going in new directions, or perhaps returning to some older ones.

As for the rest of the opposition, the liberal-socialist MSZP trailed Jobbik at 10.05% and 20 seats (down from 29 in 2014), the EU-friendly Democratic Coalition (DK) won 4.52% and 9 seats (up from 4), and the Green LMP won 4.02% and 8 seats (up from 5). In 2014, the MSZP and DK had been in a coalition with several other Leftist parties, called Unity; a similar coalition did not manifest this time. And given that, even when taken together, the Left-wing parties won only a few more seats than the minority Right-wing party, the latter of which actually slightly increased its power, this is an indication that the Hungarian Left has once again completely failed – as it also failed to do in 2010 and 2014 – to develop any program that appeals to a large number of Hungarians, in spite of some marginal increases. Combined, the Right-wing parties now control nearly 80% of the Parliament. This will surely lead to a great deal of shakeup and soul-searching among the Left in the months and years to come, although for the foreseeable future it is clear that Jobbik – in whatever form it chooses to take this time around – will remain the focal point of the opposition.

Some Right-wing Hungarians to whom I have spoken are fearful that this level of success by Fidesz could actually be dangerous for the party, if not bad for the country. Since 2015, Fidesz has become more or less a one-issue party focusing almost exclusively on immigration and their related conflict with Brussels over the issue of migrant quotas. While this is certainly welcome by people on the Right both within and outside Hungary, it is nevertheless the case that they have been ignoring many other issues of concern to Hungarians, as I discussed in my last article [5] on this topic. Having a reduced majority might have pressured Fidesz to develop a wider program on multiple issues once again. As it is, this may very well entice them to become complacent and simply continue on as they have been doing. While many Hungarians obviously still support Orbán and have indicated that they agree with him that dealing with immigration is a top priority for the country, he is certainly not uncritically admired, and if he doesn’t develop a more dynamic program going forward, it could very well lead to a genuine reinvigoration of the Left and a decline in their own support. Fidesz’s popularity was already declining precipitously in the year following the 2014 election; it was only the outbreak of the migrant crisis and their response to it that reversed this trend. While it unfortunately seems likely that mass immigration is not going to go away anytime soon as a problem facing both Hungary and Europe, in a country that is beset by many problems stemming from poverty, this alone will not be sufficient to keep them in the good graces of the Hungarian majority forever.

On the positive side, this result does indicate that the Hungarian people did not allow themselves to be dissuaded and fooled by the rhetoric stemming from the Western media and the (in many cases Western-backed) opposition groups within Hungary itself – it should be mentioned that the US State Department issued a $700,000 grant to opposition media [6] in December, to name but one aspect of the anti-government campaign – that Orbán is a dictator, that Fidesz has been undermining democracy, and that most Hungarians don’t share Orbán’s concerns regarding immigration and actually favor greater cooperation with the European Union (which implicitly means accepting migrants), and don’t endorse his ongoing conflict with Soros and his minions over the impact they are trying to have on the country. Hungarians are indeed critical of Orbán, as can be seen whenever you try to strike up a conversation with one of them about him, but they clearly view him as their best option under the circumstances. And really, in surveying his competitors, it’s impossible to disagree.

For those of us outside Hungary, we can now look forward to at least four more years of a reliable partner against Brussels and Soros on the issue of mass immigration, a leader in an initiative to construct a possible illiberal alternative to the EU in the form of the Visegrád Group, and an example of a successful populist Right-wing party operating in the heart of Europe. Although here’s hoping that Mr. Orbán will not rest on his laurels and instead develop a broader approach to addressing the problems facing Hungary, both foreign and domestic.