Zardoz: Natural Order Against the Left

Posted By David Yorkshire On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledJohn Boorman’s films are implicitly white, as they address themes that pertain to people of white European descent, whether historical, philosophical, or mythical. For the latter, an example would be the film Excalibur that I recently reviewed [2]. Zardoz is a film that addresses the philosophical. This is another of Boorman’s films that the critic Roger Ebert neither understands nor cares for – and I suspect more the latter, for the film is a biting satire directed at creamy bourgeois Leftists. Beyond the satire, which is cutting rather than amusing, Zardoz falls into two categories: dystopian fantasy and sci-fi thriller. As is usual in such films, what is being critiqued is the present – in this case, the mid-1970s.

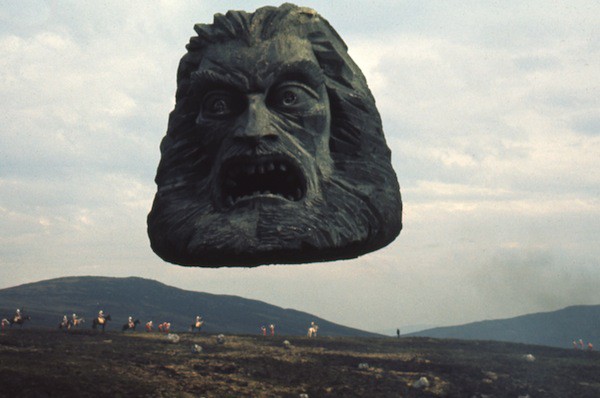

The premise, as revealed throughout the film’s denouement, is that there are two sorts of people in the year 2293: the Eternals, who live in a bubble of luxury, plenitude, comfort, and Leftist morality called The Vortex, and the Brutals, who are left to roam the wastelands. Among the Brutals are a select group called the Exterminators, who carry out the will of their god Zardoz, a giant flying stone head. Zardoz’s will is to kill other Brutals and gives the Exterminators guns to do so, saying:

Zardoz speaks to you, his chosen ones. You have been raised up from brutality to kill the Brutals who multiply and are legion. To this end, Zardoz, your god, gave you the gift of the gun. The gun is good. The penis is evil. The penis shoots seeds and makes new life to poison the Earth with the plague of men, as once it was. But the gun shoots death and purifies the Earth of the filth of Brutals. Go forth and kill.

The speech above might be criticised for its simplistic didacticism and also bizarreness, but one must consider that it is addressed to the Exterminators, who are obviously of low intellect. That said, some of the later dialogue in the film is rather too didactic and Boorman is, in places, guilty of telling rather than showing. Some of it might be excused by the film’s lack of budget – and this film really could have done with a higher budget – but some is because Boorman is guilty of heavy-handedness at times when imprinting his message on the film through dialogue. That message is, however, very Rightist, for The Vortex is soon revealed to be a dystopian idyll, an inescapable prison of luxury.

Ostensibly, the Eternals are all at peace, free from violence and death, and forever young. Their society is democratic and imposes equality on all. However, it is revealed that the men can no longer sexually perform due to their prolonged existence. Their impotence has led to women becoming leaders along feminist lines in spite of the ostensible commitment to equality. Does this sound familiar? The two most prominent are May, the scientific leader, and Consuella, the social leader, the latter stating during a lecture:

Penic erection is one of the many unsolved evolutionary mysteries surrounding sexuality. Every society had an elaborate subculture devoted to erotic stimulation, but nobody could quite determine how this [shows diagram of flaccid penis] becomes this [shows diagram of erect penis]. Of course, we all know the physical process involved, but not the link between stimulus and response. There seems to be a correlation with violence, with fear. Many hanged men died with an erection. You are all more or less aware of our intensive researches into the subject. Sexuality declined probably because we no longer needed to procreate. Eternals soon discovered that erection was no longer possible to achieve, and we are no longer victims of this violent, compulsive act, which so debased women and betrayed men.

The speech is a look at sexuality straight out of 1970s feminist pamphlets, with the only difference being a smugness in victory, dressed up as concern for the well-being of both women and men. Yet this has created anything but an idyll, with the men in particular wishing for death, as Arthur Freyn, acting as the chorus to a theatrical play, states he longs for at the beginning of the film. This introduction, however, is one of the unsatisfactory elements of the film, as it rather gives the game away, Freyn himself exposing that the film is a morality play, who he is and what the film is about. It is unnecessary and an insult to the viewer’s intelligence. It is notable that the women have also adopted more masculine impersonality, attributes, and attitudes, as witnessed in the role reversal of typical male-female interjection when witnessing the rape and violence in the Exterminators’ daily life:

Woman 1: Terribly exciting.

Man: What of the suffering?

Woman 2: Oh, you can’t equate their feelings with ours. They’re just entertainment.

This titillation at violence when removed from violence itself is at the heart of the female bourgeois psyche, and to a lesser degree in the male, because there is still the nagging discomfort in the male of his impotence. It is why, in our own societies, we have seen feminists not only content to ignore the rape of working-class women and girls at the hands of the non-white hordes flooding into Europe, but positively encouraging it.

This indeed bring me nicely to one of the major themes of the film: the betrayal of the working class by the bourgeoisie and the bourgeoisie’s isolation from the working class. It is revealed during the film that The Vortex and others like it (this one is Vortex 4) were created by “the rich, the powerful, the clever” as the world decayed. They created force fields around their self-sufficient country estates to keep the riff-raff out. Basically, the same people who destroyed the planet cut themselves off to live in a country idyll away from the consequences of their actions. Does this sound familiar?

There is even room for a poke at the nascent transhumanist movement here before it had even gained ground, Boorman predicting the flow of Leftist intellectual currents. An artificial intelligence that becomes more or less both a servile and constraining god is created called The Tabernacle – and again, as with Excalibur, this shows Boorman pitting Nature against Judeo-Christianity as anti-Nature. The Eternals have telepathic and telekinetic powers with the aid of The Tabernacle and can do violence by thought alone, again divorcing them from physical action. They are joined together and to The Tabernacle in a groupthink by crystals inserted into their brains, in a satire of Leftist consensus-making. Death and ageing is all but abolished, with The Tabernacle resurrecting any Eternals who die. The chief architect of The Vortex delivers this typically Wellsian Fabian speech of “Men Like Gods,” of hubris:

We seal ourselves herewith into this place of learning. Death is banished forever. I direct that The Tabernacle erase from us all memories of its construction so we can never destroy it if we should ever crave for death. Here man and the sum of his knowledge will never die, but go forward to perfection.

Ageing is reserved as punishment for dissident Eternals who go against the status quo. In this, it is revealed that the generation who built The Vortex and The Tabernacle realized the mistake of cheating death and Nature and attempted to destroy it. They were cast out as renegades by their spoilt offspring born into the comfort of The Vortex, who aged their parents into senility. It is notable that the leaders of the founders of The Vortex are male, their successors spoilt daddy’s girls that one sees everywhere at university. Yet even among these spoilt offspring, their unnatural existence has created virulent versions of the complexes Leftists have today. There are “the Apathetics,” who become passive to the point of no longer moving – an obvious satire on Jainism, which had been gaining traction in Leftist circles in the West post-1960s. There are many suicides, especially among men, just like now, but The Tabernacle always resurrects them. There are petty, spiteful acts of psychic violence, like the sociopathy we see today, borne out of a projected self-hatred. As one offender states during his trial:

I hate you all. I hate you all. I hate you all. Especially me.

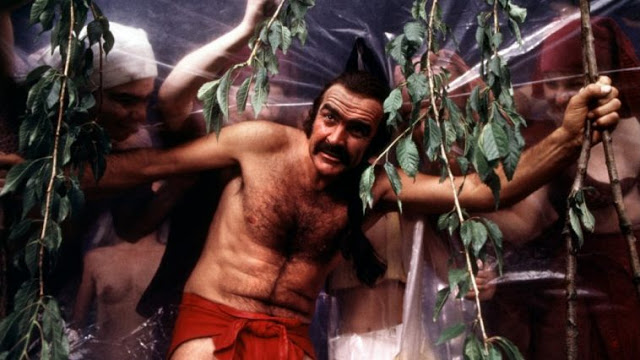

Into this dystopian idyll comes a bare-chested, mustachioed, pony-tailed Sean Connery as the Exterminator Zed, whose job it is to bring righteousness, Rightism, and Boorman’s didactic dialogue to the insufferable women of The Vortex with lines like, “This place is against life. It must die,” and “It is built on lies and suffering.” Boorman can be criticized here. Connery’s casting is interesting because Burt Reynolds was originally to be cast as Zed, with whom Boorman had worked on Deliverance, but he was unavailable at the time. Connery is similar in his rugged masculinity, but far more appropriate, as this is a very British film and Connery’s provincial accent suits the class war narrative, whereby he also represents the force of Nature against the urbane clique. A happy accident, as Bob Ross might have said.

It must be said, however, that this is not class war in the Marxian sense. Zed is seen very much as the Übermensch throughout the film, a throwback to the natural aristocrat – the warrior leader and culture bearer, as Jonathan Bowden would have it, the cultured thug. This is signified by his choice of weapon, the Webley-Fosbery automatic revolver favored by British army officers up to the First World War. It is revealed that, despite his appearance, he is an autodidact and his intelligence exceeds that of the Eternals, who, as they cannot die or reproduce, cannot evolve. Without death, new birth, and religiosity, the Eternals’ lives have been rendered meaningless. Zed brings all three in his violence, virility, and adherence to Nature as Divinity, one of Boorman’s regular themes. Zed is the latest stage of evolution and quickly surpasses the Eternals’ knowledge, yet does not abandon the body. This is the critique of the Left: that they have gone, like John Stuart Mill, into pure thought, but in doing so, their thought is no longer rooted in anything. Zed is the return of the Right, of a return of the spirit to the body, of energy to matter.

Yet it is Zardoz who creates Zed through selective breeding over generations, Zardoz who leads him into learning, and Zardoz who manipulates him into revolting against him as a false god, into seeing him as the Wizard of Oz. For the two rebellious male characters Arthur Freyn (alias Zardoz) and Friend (who acts as Zed’s haughty guide, but comes to realize he is their savior) recognize the deficiencies in themselves, Freyn wishing, in any case, as he states in the film’s prologue, to die. Both are crucially identified as artists, the artist’s role being that of honest social critic, as Rightist film director Hans-Jürgen Syberberg notes. Yet in the forced groupthink of Leftist society, they cannot perform their task. Freyn therefore gives Nature a helping hand in destroying the unnatural society, as the former leader of The Vortex identifies it with again unnecessary didacticism:

I remember now, the way it was. We challenged the Natural Order. The Vortex is an offense against Nature. She had to find a way to destroy us. Battle of wills. So she made you. We forced the hand of evolution.

This is the natural way of progress, slowly, through the generations, through eugenics, but eugenics in a natural way, through natural selection. What the Left call Progress – and they usually like to capitalize the word, like the aforementioned H. G. Wells – is nihilism. And The Vortex – the Leftist idyll – is fuelled by nihilism: the younger generation against the elder, women against men, men and everyone against themselves. And if the film sounds heavily influenced by Nietzsche, it is, and Zed as Übermensch himself quotes him, just in case you miss the point. And this critique of the Left is why the film really came under fire from the critics, because the Left do not like a dose of Truth serving up to them.

Let us take the first criticism that is always levelled at the film: the costumes. The Eternal men wear an uncomfortable blend of hippie garb and Gay Pride event costumery that displays rather too much nipple for comfort (take note, Marcus Follin). Yet the clothing reflects the men themselves: emasculated, effete, and perverse. The Exterminators are largely naked, except for a red PVC loincloth and thigh-high boots. If this resembles fetishwear, it is because it is meant to look exactly like fetishwear. And if I have just pointed out the obvious, it is because the critics completely missed the obvious. The critics should have asked the question: Who supplied the Exterminators with their “uniforms”? Zardoz. And who is Zardoz? Zardoz is Arthur Freyn, one of the Eternals, who have fetishized physical violence, rape, and death in their incapacity for any of these things. The fetishwear reflects the displaced psycho-sexual fetish itself, and if Zed resembles a ’70s porn star, it’s because Freyn rather likes him that way.

I have stated that Freyn’s monologue as a prologue to the film is unsatisfactory, but his appearance is not, for he appears as a disembodied head, which foreshadows Zardoz’s vehicle as a giant floating stone head and also the philosophical theme of the mind-body split. Even with the lack of budget, Boorman uses simple effects and, at times, rather good dialogue that one might easily miss, such as when Friend exclaims while showing Zed the Apathetics: “You idle Apathetics, melancholy sight.” It is a perfect line of iambic hexameter. Friend often shows off as an artist in the society, and this is a subtle example for the discerning viewer. That said, at times, the poor effects show through, especially where Zed punches through some “indestructible” plastic sheeting. The film also feels rather cluttered at times and I have mentioned the sometimes clunky, yet sometimes poetic, dialogue a time or two already.

Yet there are very few films that address existentialist philosophy in a serious manner and fewer still that put the sophistry of the cozy Left under the microscope. In the end, the values of the Right are restored, the values of Natural Order, with the feminist archetype Consuella submitting to the Übermensch. The ending of the film is a montage of Zed and Consuella’s contented life together, including the birth of a son, old age, and death. During childbirth, Zed takes Consuella’s hand, and again when their son comes of age and she is tempted to stop him from leaving. This shows what true masculinity and femininity are: the man both strong yet compassionate, the woman nurturing and loving. This is what the Right has always known and the Left has sought to corrupt. Accepting Rightist thought is about accepting what is, what is natural, and what one can aspire to become within the Natural Order of things.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TVakHZp5ZBE

This article originally appeared at the Mjolnir Magazine [8] Website on May 22, 2017 [9].