Kiki’s Delivery Service: Europe in Japan

Posted By Buttercup Dew On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledKiki’s Delivery Service

Written & directed by Hayao Miyazaki

Studio Ghibli, 1989

Kiki’s Delivery Service is a fantasy anime film from the world-famous Studio Ghibli, one of of the fixtures of anime in the West and darling of art-house, “world cinema” fans. It’s a small, self-contained coming of age tale of Kiki, a young Witch, and is entirely suitable and interesting viewing for all ages. I recommend it to family audiences as an Oriental supplement to more native fare, the same way an occasional taste of wasabi can liven up an over-familiar palate.

Whilst a seemingly normal family film on its own merits, it is peculiar and unique viewed from the standpoint of 2018. It is specific to its production time of 1989, when anime (previously “Japanimation” in common parlance) began to find traction in mainstream consciousness in North America, with corporations like MGM and Fox producing English dubs. Kiki’s Delivery Service was the first Studio Ghibli film distributed by Walt Disney (in 1997), and looking at the source material, style, and content, it isn’t difficult to discern why. A thematically faithful, but loose on plot details, adaptation of a children’s book written in 1985 depicting a classic “European” Witch girl replete with broomstick and black cat, Kiki’s Delivery Service is something of an international anime. Both the film and book are set in a fictional Northern European country and feature native European characters, but is written and animated in tune with Japanese sensibilities. It is this Japanese slant on “Europeanness” that makes the film an interesting watch for ethnocentrically-minded, racially-conscious whites.

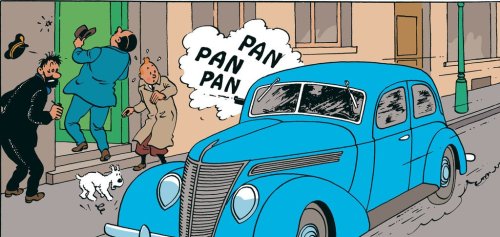

The setting in KDS is a pleasure for anime and comic book fans — readers of Herge will be able to quickly adapt to the art style of textured, detailed backgrounds and side characters, with a sparsely-drawn and more iconographic protagonist. This technique is common to illustration and animation as it makes characters and environments more “received,” detailed, and creates a photographic “otherness,” whilst the minimally-drawn protagonist becomes the viewer’s stand-in and emotional focal point; an abstracted self. The characters are drawn with natural proportions and style, being empathetic and realistic; the studio eschews the more exaggerated facial features and ridiculous hairstyles that have become the recognized trademark of superhero anime.

Kiki runs down a crowded street (above), and for comparison a panel from Herge’s “The Secret of the Unicorn” (below) featuring a famous 1937 Ford.

KDS draws heavily on European source material: Koriko, the imaginary city where the action of the film is located, “is a mixture of several cities like Naples, Lisbon, Stockholm, Paris, and even San Francisco, so one side is like the edges of the Mediterranean but the on the other side seems to border the Baltic Sea,” according to Miyazaki, the film’s director, and is drawn as such, with pastel shades and watercolor textures. The clock tower present on the cover of the original 1985 book is present in the center of Koriko, at the top of a series of undulating slopes replete with tramlines — as if San Francisco had been founded in parts of southern Italy (the clock tower, incidentally, recurs in other Witch-themed ephemera, like indie videogame hit Mystik Belle and more recent anime Little Witch Academia). When Kiki first arrives in the city, she feels distinctly out of place as a young Witch, being from a different family than the working European folk, privy to special powers and folk traditions, and casts sad and resentful eyes at clothes and shoes she cannot afford in the Parisian shopping district. She stands out as bizarrely dressed to the young girls passing by in summerwear.

Kiki is there on a mission of self-discovery (unbeknownst to her), as part of a Witches’ ethnic quest to settle new lands. The book remarks:

At thirteen, a witch had to leave home and begin a new life on her own. Picking a night when the full moon shone brightly, she would embark on a journey to look for a town or village where no witch already lived. There she would find a home and a way of putting her witchcraft to good use. Of course, this was quite a big adventure for a young girl. But witches’ powers had dwindled and their numbers had drastically decreased, so it was necessary in order to prevent the extinction of their traditions.

Which is quite a bold, multilayered statement with which to open a children’s book. The book features Kiki as more adult-looking in illustration than the film; the black dress and broomstick is characteristic of English folklore; without getting too deep into Witches and their demonological origins in Roman and Medieval Europe, suffice to say that Witches are traditionally malicious. The idea of a “coven of Witches,” old women who are keepers of ancient rites and ways, is a matriarchal mirror to the patriarchy and male-exclusive Männerbünde, and warriors’ “Boys’ Own” clubs. It is again against convention that a younger member leaves a group to seek knowledge; normally, a boy or girl joins a patri-/matriarchal society in pursuit of it. But nonetheless it is established that Witches are guardians of mystical rites, an outsider group, with their own interests and ken. Unlike clannish Shakespearean Witches who prey upon the masses and use their esoteric means to gain political leverage, the Witches-next-door of Kiki’s world exist to help out.

[4]

[4]The original Kiki, looking more Brothers Grimm in black and white

This Japanese mirror to European folklore fails to capture our history and hangups. Shinto and Buddhist ideals are alive and well in Japan and regularly feature as a fact of life in contemporary anime. For example, the currently popular slice-of-life anime Nichijou (My Ordinary Life) features a character determined to disprove the existence of spirits, the supernatural and demonic influences, only to become possessed of this materialistic absolutism and vandalize a temple (“Sometimes, a demon is just a person”). Characterizing a Witch as a non-malicious, wandering do-gooder (like a nomadic medicine seller or Ronin) is a Japanese peculiarity and is deeply unfamiliar and almost heretically suspicious in Christian, and later secular, Europe. Further still, the Witch in question, being a 13-year-old girl in search of gainful employment, is humanizing to a degree that, outside of an anime context, seems simply baffling; Hermoine Granger at least remained in Hogwarts School of Wizardry and Witchcraft and did not attempt to start a high-street potions business.

The full Moon is a common cultural touchstone for both Europe and Japan; druiding and Pagan revivalism still centers on the full Moon [5] (“I have come to catch the Ogam Observance of the Full Moon — a druidic ceremony that marks the exact moment of the moon’s zenith”); in Japanese pop culture, it is an overbearing Moon that threatens to crush Hyrule in The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask. In her show, Rei of Neon Genesis Evangelion, an agent of death, rebirth, and transcendence of time appears with the full Moon in both opening and closing credits (fittingly to the sound of “Fly me to the Moon”). The Moon in both cultures (excluding Christian monotheistic influence) has always served a dual function: of representing the strongest point of spiritual immanence, and also when normal life is most threatened by supernatural apparition, demonology, and those wielding esoteric knowledge.

Kiki’s departure to Koriko takes her through the Ghibli rolling hills, and she encounters another, more arrogant Witch on a similar quest. The first half of the film shows her settling into Koriko after being offered bed and board at a baker’s, and she adapts to working life as best she can, with a bare room and only her cat Jiji for company. Using her broomstick aviation, she is able to support herself, but battling the weather, correcting mishaps, and dealing with ungrateful customers takes an emotional toll. Other characters remark that she’s working so hard, “at just 13!”

The characters of Koriko are drawn as white Europeans, but the pattern of society does not reflect white societies or our conception of ourselves. The pacing of the film is incredibly languid until the dramatic twist is introduced. When Kiki gets into trouble with a policeman, he is wearing a ridiculously tall hat — anime in general being given to excessively ornate Western clothing for reasons the Japanese best understand themselves — like the rest of pseudo-Europe, this cop is a facsimile and doesn’t represent whites or white sensibilities. When Kiki goes into the house of an old woman on a delivery errand, she is enlisted to help light an oven to bake a fish pie. I thought, “This is it, time for these Witches to try and bake Kiki!”, but the old couple’s motives turned out to be entirely innocent. Another hiccup is that everyone is just so gosh-darned happy. Koriko is an excessively bright and trusting place, with nary a hint of crime, and the national aspiration centers on its airships and aviation (in keeping with the themes of flight as personal realization and departure).

For contrast, the French animated fantasy-comedy The Triplets of Belleville (or, in the UK, The Belleville Rendevous) centers on kidnapped cyclists and a sociopathic mafia and is much, much darker in color palette, narrative, tone, and so on — unlike the idealistic perfection of Kiki and her coven, the witchy old women of Belleville (gifted with the craft of improvisational musicianship) are drawn as persistent relics in a state of struggle, spindly or overweight and universally hunched under their hats; dogs droop, mafia men sneer, and the cyclists gurn, wheeze, and grunt through their trials, more abused racehorse or greyhound than human.

Again, this is a family film, but when us whites look at ourselves, we can tend towards the tragic-romantic or the tragi-comic, self-depreciation, gallows humor, the sardonic and ridiculous. In Kiki’s world (and anime at large), this element is almost entirely absent or manifested by otherworldly apparitions (for an extreme example, A Letter to Momo shows comedic demons who play the goof to an ordinary girl). It seems the Japanese are uncomfortable making dark jokes about themselves, even when looking through a European-tinted lens. It is this reverence for the ordinary which both beautifies Japanese society through well-regulated lifestyles and social harmony, and yet makes anime often incredibly tacky in its excessive seriousness and melodrama. Thankfully, extreme over-reaction has been toned down to suit the subject, and Kiki’s story centers on introverted self-realization over social capability.

The principal drama of Kiki’s Delivery Service comes from her losing her ability to fly, not from the malicious outside agency of a cartoon villain, but from simple exhaustion. This clever twist takes the film into uncharted territory — a principal narrative plank has been removed, and both Kiki and the audience are left in a state of existential uncertainty. Fraught with overwork, her ability to take off simply departs her. Depression and apathy go hand in hand with the disenchantment of the world and the departure of spiritual confidence, and Kiki has hers robbed through the grind and ingratitude of her customers. She also loses her ability to talk to her cat Jiji, a painful maturation process of accepting that animals are just animals.

It is a clever critique of atomizing urbanization — Miyazaki states in the foreword to the accompanying art book that, “[i]n today’s society, however, where anyone can earn money going from one temporary job to another, there is no connection between financial independence and spiritual independence. In this era, poverty is not so much material as spiritual . . . It is usually felt that the power of flight would liberate one from the earth, but freedom is accompanied by anxiety and loneliness.” Kiki, initially enchanted by the bright lights and “big nothing”[1] [6] of Koriko, quickly finds herself alone and aimless without a goal beyond simply getting by. During the pivotal scene, Kiki collapses, both physically and emotionally.

When Kiki goes to the house in the woods to reconnect with her artist friend Ursula, she finds she is a “Witch” of sorts, able to conjure realization of what is hidden deep in the soul and invisibly permeating the everyday. She has been working on a painting of Kiki since seeing her fly over. Whereas Kiki grew to accept her abilities as mundane, for her artist friend, they are inherently mystical and their presence almost a divine revelation. Viewing herself through the eyes of another, Kiki is able to reconnect with her sense of self and ancestral Witchhood and regains the confidence to return to flight.

[7]

[7]Superficially, as Miyazaki intends, the film revolves around the contradiction between freedom and dependence. On a slightly deeper level, we can take Kiki’s characterization as a Witch as being more than just a useful plot device to propel a young girl to the big city. We can also use her to outdo the modern world. She is wooed by a boy obsessed with aviation, Tombo, who eventually goes to see the airship, the Spirit of Freedom, as it arrives in town, something foreshadowed recurringly throughout the movie in radio and television broadcasts. The Spirit of Freedom is a monstrous airship characteristic of steampunk-Victorian pseudo-Europe, and the Europe of the late 1800s and leading up to the First World War, before the Hindenburg and mechanized slaughter of the trenches left Europeans bereft of the self-confidence to carry the finery and social mores of the era to the present day.

Tombo the aviation whiz-kid is Kiki’s secular, scientific analog; presumably raised on Popular Mechanics magazines, he’s sort of reminiscent of a 1950s America and carries the same archeofuturistic (then, simply futuristic) optimism. Much like Kiki herself, the airship — which originally arrived in Koriko with overwhelming optimism and pride — is wrecked by adverse weather and breaking free from its bonds; in Stirner’s contemptful words, “Freedom only teaches: Get yourselves rid of everything burdensome, it does not teach you who you yourselves are . . . the free-one is the freedom addict, the dreamer, the romantic.”[2] [8] It is the bonds of friendship that propels Kiki to take to flight to rescue Tombo from the faltering airship, ruined and capsized by excessive freedom on the town’s central clock tower (another Klok against time). It is the ancestral knowledge carried by Kiki which enables her to soar above the everyday and return the Faustian, mechanically-obsessed Tombo to groundedness, rootedness, and being in-and-of a place.

Perhaps if Europeans are to regain their spiritual self-confidence and renew themselves, it is time to abandon fanaticism for the spirit of freedom, and instead pioneer a return to the occult and ancestral; to make a return to the world of Witches’ covens under a watchful Moon.

Notes

[1] [9] A term for Andy Nowicki’s New York, in Under the Nihil [10] (San Francisco: Counter-Currents Publishing, 2011).

[2] [11] Max Stirner, The Unique and Its Property, translated by Wolfi Landstreicher (Baltimore: Underworld Amusements, 2017).