An Esoteric Commentary on the Volsung Saga, Part I

Posted By Collin Cleary On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled [1]

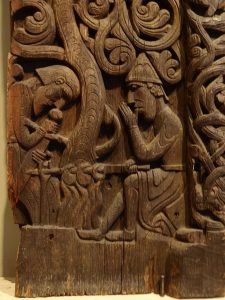

[1]A carving depicting Sigurd sucking the dragon’s blood off his thumb, from a stave church in Setesdal, Norway.

4,517 words

Part II here [2]

The purpose of this essay is to offer an account of the hidden meaning of the Volsung Saga (Völsunga saga). In drawing out this meaning, I will approach the saga from a Traditionalist standpoint, broadly speaking; i.e., from the standpoint of Guénon and Evola. I will touch on some details concerning the relation of the saga to other sources, but I do not aim to provide anything like the sort of account a historian or philologist might give.

Some introductory remarks are necessary concerning the sources, and my methodology. The Volsung Saga is a late thirteenth-century Icelandic prose account of the clan of the Volsungs, which includes the heroes Sigmund and Sigurd.[1] [3] Its sequel is Ragnar Lothbrok’s Saga (Ragnars saga loðbrókar), and in the only extant manuscript of the Volsung Saga the text is followed directly by the saga of Ragnar. (I will also have a few things to say in this essay about that saga as well.) We know that the Volsung Saga is based on older sources. Significant parts of it draw upon material in the Codex Regius, which was compiled earlier in the thirteenth century. Snorri Sturluson, in his Prose Edda (compiled ca. 1220), includes a summary of most elements of the Sigurd story, and quotes material found in the Codex Regius.

However, the stories of the Volsungs must be considerably older. The Ramsund carving in Sweden depicts episodes from the life of Sigurd, and it is thought to have been carved around the year 1030. We must also mention Beowulf, which includes the story of Sigmund (“Sigemund the Wælsing”), though in this version he is the dragon-slayer, not Sigurd. The manuscript of Beowulf was produced between 975 and 1025. We can safely assume that these stories had to have been circulating for a very long time before anyone thought to carve them in stone, or to incorporate them into Beowulf and any other texts. It is impossible to say when they had their origin, as the first versions were undoubtedly oral. Suffice it to say that we are dealing with a tradition that is centuries older than the first texts that give an account of it.

As Jackson Crawford has stated:

Seen in a wider context that takes in both their ancient roots and the widespread and long-lasting fame of their heroes, [the Volsung Saga and Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok] stand out not as the sources of a mythical tradition but as the culmination of it. The Saga of the Volsungs, in particular, is the masterpiece of an author who inherited a magnificent and deep-rooted set of conflicting but related traditions, and made from them a sweeping story that has become one of the longest-enduring and most influential sagas.[2] [4]

Part of the problem with dating the sources of the Volsung Saga is that, as Crawford states, the text weaves together a number of stories that often seem loosely related. Some of these stories may be older than others, and have very distinct origins. It is likely that connections between them were made prior to the composition of the thirteenth-century saga, and it is, of course, possible that they were always connected in the minds of poets. Many elements from the Volsung Saga are to be found, as already noted, in the poems of the Codex Regius and in Snorri’s Prose Edda. What is missing from those sources, however, is most of the stories recounted in the Volsung Saga concerning the generations of Volsungs prior to Sigurd. Still, it seems likely that those stories were circulating in other forms, now mostly lost to us, long prior to their usage by the anonymous author of the saga. As already noted, Beowulf features Sigmund, father of Sigurd, though it makes the father the dragon-slayer. It is possible that there were other, older versions of Sigmund’s story in which he was also depicted as a dragon-slayer – and also possible that originally the stories of Sigmund and Sigurd had little or no relation. Connecting them may have been the inspiration of some later poet who could have transferred characteristics from one hero to the other.

Parts of the Volsung Saga seem to simply be digressions, and some parts contradict others! For example, in one chapter the tree that grows in Volsung’s hall is an oak, in another chapter it’s an apple tree. The saga also gives two conflicting accounts of the meeting of Sigurd and Brynhild. In addition, there are plot difficulties that strongly suggest that the saga writer is weaving together tales that have little connection. A good example of this is the story of Sinfjotli [5], son of Sigmund. After considerable dramatic build-up (including his conception as a result of the incest of Sigmund and Signy, his lycanthropy, etc.) he meets an anti-climactic end, and does nothing much (plot-wise) to pave the way for Sigurd, the apotheosis of the Volsungs. (Wagner was thus wise, in his version of the story, to swap Sinfjotli with Sigurd/Siegfried and make the latter the product of the incestuous union.[3] [6])

All of these considerations seem to count against any approach to the Volsung Saga which would interpret it as a whole – as one, unitary tale – and offer an account of its hidden meaning. Nevertheless, that is just the approach I will take here, and it is not hard to justify it. First of all, I have already raised the possibility that these seemingly disparate and loosely-connected tales had been connected in the minds of poets for a very long time. In fact, it is possible that all the basic plot elements of the saga were in place from the beginning, at least in germinal form. The fact that some parts seem almost like separate, standalone stories could be due to the fact that elements of the original plot were extracted and elaborated upon individually by many generations of poets.

A second consideration is that even if the writer of the Volsung Saga wove together separate, only loosely-related tales, it is still true that this writer had literary intentions in combining the stories in the way that he did. We have to avoid the temptation of thinking that this saga is simply a handy compilation of stories. It is easy to fall into thinking about it this way, because we have no idea who the saga writer was. We thus tend not to think of him as an individual author, with his own perspective and intentions, but rather as a mere “anonymous compiler” of traditional stories. This could well be as big a mistake as thinking that Wagner – whose Ring weaves together the Volsung Saga with the Nibelungenlied and the stories of the gods in the Eddas – was merely grafting together different stories and had no message of his own. Thus, even if the Volsung Saga presents a patchwork of older tales, it is still entirely possible – indeed, it is likely – that the author created this tapestry because he saw deep connections between the stories, and had some meaning to communicate. It is the purpose of this essay to bring out that meaning – which I will argue is perennial or Traditional.

Finally, it must be mentioned that interpreting all texts as unitary wholes is a sound, hermeneutical methodology. Some texts only seem fragmentary on a first reading. On a deeper level, however, they exhibit unity. We would completely miss that unity if we never questioned whether our initial impression of the text might be superficial. In other words, if there really is a deeper unity to a text we are guaranteed to miss it if we don’t even try looking for it. Therefore, we have to try the experiment of reading every text, even the most seemingly disjointed, as if it is a whole, with a unity of underlying meaning. If that meaning is there, then hopefully this approach will uncover it. Of course, we must also work against the temptation to read meaning into texts where it is not present. In the case of texts like the Volsung Saga, familiarity with multiple sources from the same tradition, with the cultural context, and with perennial mythological and symbolic forms can help us both to recognize meaning, and to avoid implausible interpretations. This is a balancing act, and it is far from being an exact science.

Hopefully, the result of the present investigation will be to reveal that the Volsung Saga is a text rich with esoteric significance. I hope to shed light on significant parts of the text – though some elements may remain mysterious. And I assume I do not need to convince my readers that this investigation is worthwhile. In the cycle of Volsung tales we have the greatest heroic legends of the Germanic tradition. It is here, as many have recognized, that we find vitally important clues to the values and character of the Germanic peoples. And it is here, I will maintain, that we find veiled indications of esoteric teachings of a highly sophisticated nature. Finally, as all readers of the saga will discover, the text – even when taken on a superficial level – is exciting, endlessly imaginative, and often unsettlingly twisted and macabre.

The divisions of my commentary follow the chapter divisions in most editions of the text.[4] [7]

1. Concerning Sigi, a son of Odin

The clan of the Volsungs are not referred to by that name from the very beginning. It takes its name from one of its greatest exemplars, who we will meet later on. The story of the clan begins with Sigi, whose father is Odin – so we may actually say that Odin is the first Volsung (what this name means, or may mean, will be discussed later). Now, we know that this god is crafty, and does everything for an ulterior motive. His two chief concerns are acquiring wisdom, and building an army of the dead that will fight by his side at Ragnarok. (These concerns are not unrelated, of course, since the wisdom Odin acquires can help him in the final battle.) We may thus assume that Odin’s purpose in siring Sigi is to create another warrior whom he can later “harvest” (to use Jackson Crawford’s term) for his army in Valhalla.[5] [8]

What we will find, however, is that Odin’s actual plans are far more elaborate. With the Volsungs, he aims to create an entire clan of super-warriors, each generation of which is (in most cases) greater and stronger than the previous. In order to accomplish this, of course, selective breeding is necessary. The most dramatic instance in which this becomes a plot element is the incestuous union of the Volsung twins, Sigmund and Signy, which produces the hero Sinfjotli. As I will discuss in a later installment, the apparent rationale for this union (which must, I will argue, be credited to the crafty Odin) is the desire to produce a “pure” Volsung, without any admixture from outside the clan. In the case of the first Volsung, Sigi, we are given absolutely no information about the mother on whom Odin sired this boy. Thus, we are left with the impression that Sigi may be – just possibly – a “hypostasis” of Odin; another “pure Volsung,” the one who, armed with an undiluted heritage from the god himself, sires the rest of the clan.

With such parentage, one would expect great things of Sigi – but, at least at first glance, the character seems disappointing. Sigi has a friend named Skathi who is considered “powerful and great.” However, the text tells us that of the two, Sigi was more powerful and “from a better family” (hardly surprising, given his father). Note, however, that the text does not call Sigi “great” (mikill). One day Sigi goes hunting with Skathi’s slave, Brethi, who was as “talented and accomplished as many men who were considered his betters, and perhaps even more so than some such men.”[6] [9] The result of the hunt is that Brethi kills more animals than Sigi, and more desirable ones as well. Enraged at being outshone by a slave, Sigi murders Brethi and conceals his body in a snowdrift.

Later that evening, Sigi compounds the crime by lying about it, saying that he lost track of Brethi in the forest and has no idea where he is. Skathi distrusts him, however, and his men go searching for Brethi and soon uncover his body. Sigi then receives the ultimate punishment for his crime. He is outlawed, cast out of society: “he could not remain at home with his father any longer.”[7] [10] This is an interesting comment, for one would expect that Odin might have appeared, sired Sigi, and gone on his way. Instead, Sigi has apparently been living with Odin. Where? Probably not in Valhalla, since Sigi has to be living among men in order to be outlawed. Or could it be that Sigi has been fostered by a man? (Fosterage is a recurring theme in the saga.)

In any case, Odin does not abandon Sigi as a result of this shameful crime. Instead, it seems to strengthen their bond. The text tells us that Odin travelled with Sigi “a long way,” after the latter was commanded to leave his land. Their travels together end when they reach “some warships” – presumably a gift from Odin to Sigi. Indeed, when they part, Odin bestows an entire army on Sigi, who is “victorious in many battles.” Eventually, Sigi gains a kingdom for himself: “Hunland.” He “marries well” and achieves renown as a great king and mighty warrior. He and his wife have a son named Rerir who was “already a large and accomplished man at a young age.” The size, strength, and virility of the Volsungs are frequently mentioned in the saga, and, as noted already, they seem to increase with each subsequent generation.

Let us now address some of the peculiarities in the story of Sigi. To be “outlawed” is to be placed outside the bounds of society – its rules, mores, and of course, its protection. In essence, however, the practice of outlawing a man really consists in recognizing, officially, a status he has already chosen through his own deeds. The man who murders another member of his society, for example, has actually chosen outlawry – he has chosen to live outside society’s rules. What is significant about Sigi’s story is that it is not just his murder of the slave that breaks society’s covenants. Everything that leads up to it is also “outside the law,” or outside the norm.

Consider: Sigi not only goes hunting, alone, with a slave, he does so with another’s man’s slave. This is quite peculiar. Sigi, a free man who is “powerful” and of high birth, goes hunting with one of the lowliest members of society, who is not his to command. What is even stranger is that Brethi, the slave, is not there merely to carry Sigi’s weapons and help him bring home the kill. They are actually hunting partners, and Sigi, at least, sees them as competing. But such a relationship is one that is normally found among men who are social equals. Within the bounds of the society, these men are anything but. Keep in mind, however, that the story has them both stepping outside those bounds: they enter into the forest, into the wild, to go hunting. In the Indo-European tradition, the forest represents all that which is outside the social world. For example, as Kris Kershaw notes, the Sanskrit term usually translated “forest,” aranya, actually means what is “other than the village.”[8] [11] (The Aranyakas, which are Hindu esoteric texts, derive their name from this term.)

Symbolically, Sigi and Brethi thus step outside the constraints of social norms. In the forest, as hunting partners, they are no longer free man and slave. Stripped, temporarily, of these social roles, the only thing that sets them apart is their skill at the primal, masculine activity with which they are engaged. And it is the slave who shows himself to be the better man! This too, of course, is contrary to what is “the norm.” We expect the free man, the powerful warrior, to be the better hunter. But the social roles do not reflect reality in this case: the “slave” is in fact master. Removed from the boundaries of society’s laws, alone in the forest, Sigi attempts to reassert his superiority in the only way he can: by killing Brethi.

Note that he does not chastise him or remind him that he is only a slave – for this would be a weak and artificial way of asserting superiority. Sigi knows that Brethi has proved himself better at the manly art of coping in the wildness that lies outside society – and Brethi knows that he knows this. To respond to Brethi by diminishing him, by reminding him of his social position, would be a craven form of compensation, and an appeal to the rules of the social world that has, in effect, been invalidated by the results of the hunt. Under the circumstances, killing Brethi is an honest, and manly response – if a bit of an overreaction (beating him up might have been sufficient). As an attempt to assert his natural superiority over Brethi, Sigi’s act is quite effective: Brethi may out-hunt Sigi, but Sigi can kill Brethi. In the end, Sigi does prove himself to be the more powerful man. Of course, in so doing, he removes any possibility that he can reenter the society that he and Brethi had left.

Now, we must assume that everything that happens to Sigi is probably somehow orchestrated by Odin. Why, then, does Odin allow his son to be placed in this situation, and to act the way that he does? Why does he bring Sigi to the ignominious fate of becoming an outlaw?

First of all, it must be said that Odin does not typically make anyone do anything. Instead, it is their own characters that typically make them do what they do. So, a better way of seeing the situation is that Odin places Sigi in this set of circumstances (or allows him to be placed) knowing that Sigi’s character will likely produce this sort of outcome. In short, Odin knows that in order for Sigi to fulfill his destiny, he must become outlawed. And the particular circumstances of his outlawry are significant as well. Remember that Odin is breeding a clan of super-warriors whom he can harvest for his army of the Einherjar. Such a race cannot prove itself within the constraints of society – it must break those constraints. Thus, Sigi, the first of the Volsung line, is placed in a primal situation in which social norms are first invalidated (the slave appears as “master”) and then completely rejected (Sigi murders Brethi).

Ultimately, the male warrior spirit always displays itself outside society, or on its margins. Even when men are fighting to defend their own society against outsiders, the fight happens essentially in a state of nature: There is no social authority governing the two sides in their confrontation, and all the rules that normally constrain man’s aggression are cancelled. Of course, in addition to warriors who fight to defend their tribe, we also have the phenomenon of rogue “warriors,” such as pirates, bandits, raiders, and gangs of all kinds. In the world of the Germanic tribes, such activities were not frowned upon, so long as these men did not victimize their own tribe and kin. Indeed, the act of raiding other tribes or slaughtering and robbing strangers was admired and served to enhance reputations. (This was also true of other Indo-European societies, including the archaic Greeks.[9] [12]) We will encounter a dramatic instance of this later in the saga, when we come to the adventures of Sigmund and Sinfjotli.

Thus, there is a duality to the figure of the warrior. His prowess can be channeled into a force for protecting the tribe and preserving social order. On the other hand, if his prowess is not so channeled, it becomes a force of destruction. The latter way of life, which detaches the warrior from a social role of protection, is always powerfully attractive to men. When the warrior acts as protector of the tribe, he is essentially acting as protector of women and children, and thus as a servant of nature. But the human spirit – especially the male spirit – is characterized by the desire to disengage from natural ends and to create something noble and beautiful for its own sake – something that may be wholly impractical, and do nothing to advance survival and procreation. As D. H. Lawrence once wrote, “the desire of the human male is to build a world: not ‘to build a world for you, dear’: but to build up out of his own self and his own belief and his own effort something wonderful.”[10] [13]

Since men find fulfillment in the role of warrior, there is thus always the possibility that they may choose to pursue that way of life for its own sake, rather than for the good of the tribe. In other words, what often begins as Dumezil’s “second function” of protection becomes a way of life unto itself, with its own values quite distinct from those of the village (which the warrior may, indeed, come to scorn). In this case, the warrior judges himself not in terms of whether he is effective in protecting the tribe, but whether he has achieved honor within the warrior band, through demonstrating his prowess and loyalty (to the band, not the tribe). It is obvious that the modern conception of the warrior, who is solely concerned with “defense” and with “peace-keeping,” is a degraded form. It is yet another illustration of the “feminized” nature of modernity, in which masculine, warrior virtues are only allowed expression when they are placed in the service of the womanly values of comfort, safety, and security.

In the ancient world, it must again be emphasized, both types of warrior were admired: the one who acts as protector of the tribe, and the one who acts independently, even as a force of pure destruction. The former was seen as “of the village,” and the latter, of course, as “of the forest.”[11] [14] One strongly suspects that our (male) ancestors had greater admiration for the warriors who moved outside society, fighting and conquering for its own sake. And there is good reason for this. It is such men who, very often, found new tribes, new kingdoms – who make of themselves new kings, whereas the other type of warrior, the tribal protector, fights only to preserve what already exists, which he did not create, and always in the service of someone else.

Odin is the god of both types of men: He is the god of armies pledged to defend their tribe, as well as god of brigands, raiders, ruffians, bandits, and outlaws of all kinds (just like the Indian Rudra, and the Greek Hermes).[12] [15] As the greatest of all warrior bands, Odin’s Einherjar serves as a paradigm against which all others are judged, and with which the Germanic warrior bands identified, seeing themselves as already dead and as one with their ancestors. But which sort of warriors are the Einherjar? They are loyal to no tribe. They are loyal only to each other – to the warrior band – and to Odin. And they live only to fight with each other on a daily basis, and eventually, to fight at Ragnarok. Thus, they most closely resemble the second sort of warriors described above: those that live independently of the tribe, devoted solely to the warrior life itself and the warrior code. (And the fact that the Einherjar were regarded as the ideal, as the paradigm of the warrior band itself, confirms my claim earlier that it is the second sort of warrior who was most admired, not the “protector of the tribe.”)

Of course, one might object that the Einherjar are recruited by Odin precisely as a protective force: an army that will protect him, and the tribe of the gods, against the forces of evil that will be unleashed in the final battle. However, this is simply not the case. First of all, Odin has heard the prophecy of the Volva and knows that he and the other gods will die in Ragnarok. Odin does not recruit an army to try to prevent this. He recruits an army because failing to fight is not an option. (And Odin’s resistance, utilizing the forces of the Einherjar, is itself something that is prophesied.) This is something that many will find difficult to understand, because modern people do not understand the concept of honor.

Ragnarok is really a battle between the forces of honor and a degenerate, monstrous, multi-form dishonor. Thus, Odin and his Einherjar are moved by the values of the second type of warrior I described earlier – the one who pursues the warrior way of life (which includes devotion to honor) for its own sake, and not with the end of “protection” in mind. At the final battle, Odin, the gods, and the Einherjar will face an array of monsters sired by the dishonorable Loki, all described as the epitome of treachery and evil. This includes the Midgard-serpent, who is described at one point as “honorless.”[13] [16]

And fighting those creatures will be Sigi, alongside many other powerful warriors. Again, Odin’s purpose in creating Sigi is to give rise to the greatest of all warrior clans. Of course, Odin only seeks greatness for Sigi so that he may, at some later point, end his life and call him to Valhalla, where he will take his place as a useful member of the Einherjar. In order to make Sigi truly great among men, and worthy of a place at the table in Valhalla, Odin must remove him from society. Sigi must cease being a warrior in the service of an existing social order, and become his own master, a lone wolf who will go on to create his own world. Outlawed, returned to the state of nature, Sigi must constitute a new honor and a new code – a code disconnected from the social role of warrior as “protector.”

As we shall see, it will not be long before Odin calls Sigi to Valhalla . . .

Notes

[1] [17] I have anglicized most Old Norse names and terms herein, avoiding special characters like þ, ð, dh, đ, etc.

[2] [18] The Saga of the Volsungs with the Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok, trans. Jackson Crawford (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2017)

[3] [19] Wagner also alludes to the forest adventures involving Sigmund and Sinfjotli, but in his version it involves Wotan and Sigmund, who are father and son. See my book Wagner’s Ring and the Germanic Tradition, forthcoming from Counter-Currents Publishing.

[4] [20] The chapter titles herein quote the translation by Jackson Crawford. This is the translation quoted throughout.

[5] [21] Crawford, xi.

[6] [22] Crawford, 1.

[7] [23] Crawford, 1.

[8] [24] Kris Kershaw, The One-Eyed God: Odin and the (Indo-) Germanic Männerbünde (Washington, DC: Journal of Indo-European Studies monograph no. 36), 111.

[9] [25] See Kershaw, 16.

[10] [26] D. H. Lawrence, Fantasia of the Unconscious (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 18.

[11] [27] Kershaw, 108-109.

[12] [28] Kershaw, 36.

[13] [29] Voluspa 54; The Poetic Edda, trans. Jackson Crawford (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2015), 12.