On the Sky King’s Stoicism

Posted By Huntley Haverstock On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,200 words

We judge people. Even when people express sincere suicidal feelings, we can’t help judging them. They may be exhibiting a lot of self-pity or emotional chaos, because the situation they’re in justifies it. Their circumstances may be such that we would feel exactly the same way if we were in their shoes. Still, when we see these behaviors, it nudges us towards assuming that these tendencies must be what led to them ending up in their predicament in the first place. It’s unfair, but it’s natural: This often causes us to sympathize less. And usually when people end up in those situations, things like self-pity and emotional chaos come along for the ride.

Richard “Sky King” Russell displayed none of it.

If you followed the story closely, you’re familiar with the now-iconic, simple statement [2] Russell made when air traffic control suggested that Russell could get a job as a pilot if he landed the plane: “Nah, I’m a white guy . . .” Most mainstream reports on the incident, of course, left this out.

It would be very easy to make this analysis political. Being white really did make it less likely for Russell to become a pilot. And the same mainstream media which devotes so little attention to that is now censoring Russell’s dying words because he noticed that this is the case.

This is hardly an unsubstantiated allegation. In the words of attorney Michael Pearson, who recently sued the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) [3], “A group within the FAA, including the human resources function within the FAA — the National Black Coalition of Federal Aviation Employees — determined that the workforce was too white . . . They had a concerted effort through the Department of Transportation in the Obama administration to change that. It’s the safety of the national airspace that’s at risk here . . .”

But I want to take a slightly different approach. The significance of “Nah, I’m a white guy” isn’t just that he identified race as a causal factor in his life situation. It isn’t even mainly that he did so. Rather, it was the tone. It was his calm, stoic acceptance in the face of perceived hopelessness. Something about that attitude can be strangely beautiful — a way to retain a sense of nobility in the most ignoble circumstances. Romanticizing that sentiment in art is a theme that goes all the way back to Shakespeare and beyond. What we resonate with in the story of Richard Russell is archetypal.

If I must die,

I will encounter darkness as a bride,

And hug it in mine arms . . .

— Measure for Measure, Act II, Scene I[1] [4]

Russell could have said the same thing in a number of different tones. For example, he might have said, “Fuck you, do you think they’ll ever give me a job? I’m a fucking white cis male, how many n***** diversity hires do you think are in my way?” Despite opening the same political conversation as before, it just would not have held the same fatalistic poignancy as his actual statement did. Had he delivered it in that way, Russell would have seemed unhinged. Instead, he simply said:

That is why “Nah, I’m a white guy” is such a strong statement for us. We know the score. Nah, you can’t bullshit us. We know they aren’t giving us that job . . .

The story of Richard Russell unifies two attributes that we don’t often find together. The first is masculine mastery: How did he learn to pull off a damn barrel roll without any flight training? How many men would like to believe they would be capable of pulling off a heist like this?

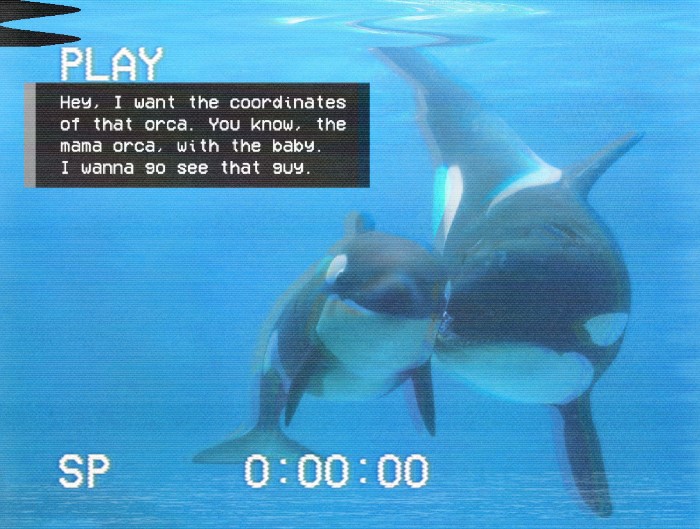

The second is his child-like aura of simplicity. Russell could have spent his entire chat with air control raving about the world’s politics and then flown into a government building. Instead, all he wanted to do was pull off one last cool thing and see a few pretty sights before calmly checking out. He even spent his final moments worried about hurting or inconveniencing other people through his actions. At one point, he said to the air traffic controller, “Oh, shoot. Man, I’m sorry about this. I hope this doesn’t ruin your day . . .” When it was suggested that he should land at an Air Force base: “I think I might mess something up there . . .” Then he asked air traffic control if they can give him the coordinates to go see “that mama orca with the baby,” in reference to this grieving orca that carried its dead calf around for seventeen days [6].

The chorus of these two attributes has created a myth to outlive the man. In that core of exasperation with the modern world, which could have led to the desire to do something to change it if only he had found a way to channel that feeling, we find an icon of our own frustrations, all melted down into a single image.

Of course, just as reports of mass suicide at the iPad-manufacturing Foxconn facility led managers to install safety nets preventing suicide by jumping [8] rather than taking a serious look at why people wanted to kill themselves in the first place, Michael Huerta of the FAA has assured us [9] that he takes security “very, very seriously” and plans to “change protocol or put additional steps in place” to make sure baggage handlers don’t have any more opportunities to get that close to the planes.

The feeling that the modern world isn’t worth living in is something to which most of us can relate. In a mass consumerist, atomized society, we’ve all become completely replaceable. Hit popular music even features choruses like [10], “I can have another you in a minute . . . So don’t you ever for a second get to thinking you’re irreplaceable.” And the modern world sings this chorus to us from every corner. There’s always someone who can do our job faster or for less money in another country. There’s always someone in the dating market willing to put out a little faster. Divorce rates continue rising. There are continually fewer and fewer meaningful bonds that actually make people “irreplaceable” as time goes on.

The nation as a whole won’t mourn Richard Russell’s death, because they see him as entirely replaceable. The airline probably had another baggage handler the very next day. Within days, if not hours, the news cycle doubtless had another shocking news bite to broadcast repeatedly. Only Russell’s family will truly feel he is “irreplaceable” — but our nation is no longer held together by bonds of extended family. But the fact that we are searching to hold on to this lost sense of common roots is why we will mourn his passing.

As Nietzsche put it, it should be possible “[t]o die proudly, when it is no longer possible to live proudly.” The modern world offers fewer and fewer of us a life that could be called “proud.” However undignified suicide may be in general, Russell’s method was as dignified as any act of suicide could possibly be. Seeing that, we can only assume that he found in death a dignity he was unable to obtain in life.

Note

[1] [11] The analogy here is intensified: “to die” in Elizabethan slang also means “to have an orgasm.”