Wobomagonda: The White Devil

Posted By Fenek Solère On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled [1]

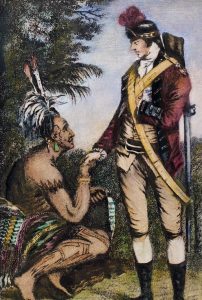

[1]“Major Robert Rogers & an Indian Chief,” from Fort Ticonderoga: A Short History by S. H. P. Pell.

6,042 words

“Their captain was Robert Rogers, of New Hampshire, – a strong, well-knit figure, in dress and appearance more woodsman than soldier . . . He was ambitious and violent, yet able in more ways than one, by no means uneducated, and so skilled in woodcraft, so energetic and resolute, that his services were invaluable.”

–Francis Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe (1885)

I can vividly recall tramping the bastions and grassy demi-lunes of Fort Ticonderoga, formerly Fort Carillon, Pierre de Rigaurd de Vaudreuil’s star-shaped fort designed by a Canadian-born French engineer, Michel Chartier de Lotbiniere, in the style of Vauban – an edifice built on the strategic confluence of Lake Champlain and Lake George in upstate New York. I was in the company of a reenactor from Jaeger’s battalion, fresh from the War College Conference, eager to share his knowledge. He was clad in brown, fly-front breeches and a long, dark green waistcoat. His speech became increasingly animated as he described how Abercrombie’s 42nd Highlanders had been cut to pieces as they attempted to chop their way through the abatis – trunks of trees that had been deliberately felled to slow the British advance – so that the French regulars aided by the cunning Coureur de Bois sharpshooters could pick them off one by one as they forced their way through the tangle of knotty branches.

My imagination instantly filled with images of tricorn hats and Union Jacks flying proudly in the breeze, floating across the water, a mass flotilla carrying sixteen thousand redcoats and colonial militia up the lake to land at Bernetz Brook. Rogers’ Rangers, supporting Gage’s 80th Regiment of Light Armed Foot, drove the French scouts behind their entrenchments, and the gallant Lord Howe, who had long championed the skills of the irregular units, was killed in an ambuscade at the point where Bernetz Brook enters the La Chute River. This was an incident precipitated by Phineas Lyman’s Connecticut regiment, which suddenly and unexpectedly came face-to-face, in the gloom of the forest’s half-light, with Captain Trepezet’s retreating French reconnaissance party.

Howe, an advocate of modern tactics rather than the fixed bayonet-charge favored by his superior, Abercrombie, may have proved wise counsel if he had survived the skirmish at La Chute. The British, despite their overwhelming numeric superiority, went on to lose a catastrophic confrontation with the wily Montcalm, with witnesses describing how they “fell exceedingly fast” and were “cut down like grass,” and were eventually forced to “shamefully retreat.”

Much like Braddock’s ill-fated march on Fort Duquesne in 1755 – the column of refugees being molested and butchered by renegade gangs of war-whooping Indians after the surrender of William Henry in 1757, and Wolfe falling to a well-aimed musket-ball on the Plains of Abraham at the siege of Quebec in 175 – I started to envisage hundreds upon thousands of spectral grey faces staring out from under bonny Scotch bonnets, as they fell prey to the onrushing hatchet-wielding Hurons, their sharp scalping knives already painted red with white men’s blood.

Yet amidst all the carnage and confusion of what Timothy Todish rightfully describes in his book America’s First First World War, 1754-1763 (1982), one rough-edged American, a colonist of Scotch-Irish descent, stands out, representing a new breed of man, a pioneer spirit, that would go on to penetrate beyond the Adirondack mountains. His protégés, Jonathan Carver and James Tute, operating under Rogers’ direct orders, took to the rivers in a canoe in search of the legendary and elusive Northwest Passage, moving ever westwards and towards the Great Plains.

Robert Rogers was the living embodiment of the Jacksonian notion of Manifest Destiny and westward expansion almost a century before the concept was even born. As John F. Ross, author of War on the Run (2009), rightfully says, Rogers was “an American creature who no one had ever seen before.” He was one of America’s first home-grown heroes, an icon whose actions filled hundreds of news-sheets and gazettes like the Boston Evening Post (1755-1760), the Boston Gazette (1755-1760), and the Boston News Letter of 1755. His name resounded throughout the Thirteen Colonies at a time when Stephen Brumwell, author of White Devil: A True Story of War, Savagery and Vengeance in Colonial America (2004), perceptively argues “there was a desperate need for good news, a need for British and American heroes. Initially you read descriptions of scouts where no one is mentioned and then there is mention of Captain Rogers, then the brave captain Rogers, and then Major Rogers in bold type.”

At last, here was someone as comfortable in the Northeastern woodlands as the Indian tribes and the French guerrillas he battled, a charismatic leader who characterized the notion of “Rugged Americanism.” He was like that other great American frontiersman, Daniel Boone, who was consciously – or subliminally – influential in the formation of James Fenimore Cooper’s fictional characters Hawkeye; the pathfinder also known as Natty Bumpo; the Deerslayer; and La Longue Carabine, in his celebrated novels The Pioneers (1823), The Last of the Mohicans (1826), The Deerslayer (1827), and The Pathfinder (1840), which comprised – along with The Prairie (1840) – The Leatherstocking Tales.

Rogers was a soldier whose exploits, as we will see, were immortalized in Francis Parkman’s Montcalm and Wolfe (1884) and Kenneth Roberts’ Northwest Passage (1937). He was a warrior who defined guerrilla warfare with his twenty-eight “Rules of Ranging.” Conceived in 1757 while resting between missions on Rogers’ Island in the Hudson River near Fort Edward, and blending the Indian’s stealthy way of war with his own innovative combat techniques, Rogers’ Standing Orders were intended to serve as a training manual for his personally-selected company of around six hundred men, and is today still revered by America’s elite fighting units, and is quoted on the first page of the U.S. Army Ranger’s Handbook. The original text includes excerpts like the following:

Whenever you are ordered out to the enemies’ forts or frontiers for discoveries, if your number be small, march in a single file, keeping at such a distance from each other as to prevent one shot from killing two men . . .

If you march over marshes or soft ground, change your position, and march abreast of each other to prevent the enemy from tracking you . . .

If you have the good fortune to take any prisoners, keep them separate, till they are examined, and in your return take a different route from that in which you went out, that you may the better discover any party in your rear . . .

If you oblige the enemy to retreat, be careful, in your pursuit of them, to keep out your flanking parties, and prevent them from gaining eminences, or rising grounds, in which case they would perhaps be able to rally and repulse you in their turn.

if the enemy pursue your rear, take a circle till you come to your own tracks, and there form an ambush to receive them, and give them the first fire . . .

So who was this man who attracted such a schizophrenic response from the British? Major General Jeffrey Amherst both admired and trusted him as a confidante, and Thomas Gage, although Amherst’s venal and spiteful successor, despised the “American upstart.” At the same time, Rogers commanded both fear and respect from tribes like the Abenaki, Nipissing, Crees, Caughnawaga, and Ottawa, as well as the leaders of French irregular troops like Charles Michel de Langlade, Durantaye, and Langis de Montegron, whose forces he often met head-on in vicious hand-to-hand fighting in the woods around Glens Falls, or sliding on sledges and rickety snowshoes along the icy stretches of Lake Champlain. The latter was a rusty, red-leafed portage of some importance, being a key crossing point between the English trade route up the Hudson and the French fur route along the St. Lawrence.

I have studied primary sources relating to Rogers and his Rangers in New York, Ann Arbor, Boston, London, and elsewhere; read all the available secondary sources, such as John R. Cuneo’s definitive biography, Robert Rogers of the Rangers (1959) and Burt Garfield Loesher’s multi-volume The History of Rogers Rangers; searched the nine boxes of papers compiled on the author Kenneth Roberts held in the Yale rare manuscript library; walked the battlefields with local guides; trod the parapets of Fort Niagara and also Fort Number Four at Charlestown, New Hampshire; and sailed across Lake Memphremagog on the anniversary of the St Francis Raid, from Vermont to the Canadian border.

What we know for sure is that Rogers was no average person. Historians and writers have described his complex life as being worthy of a Greek tragedy. He was born in 1731 to Irish immigrant parents, James and Mary McFatridge Rogers, in Methuen, northeastern Massachusetts before relocating to the Great Meadow district of New Hampshire, near present-day Concord in 1739, where his father was accidently killed after being mistaken for a foraging bear. His father had founded a settlement on 2,190 acres of land which he called Munterloney, after a hilly place in Derry, Ireland, from where he originated. Later, Rogers would refer to his childhood home as Mountalona; over time became Dunbarton, New Hampshire.

His attributes and successes were numerous, including serving in Captain Daniel Ladd’s New Hampshire militia during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), known in North America as King George’s War (1744-1748); joining Ebenezer Eastman’s Scouting Company on the New Hampshire frontier in 1747, and Israel Putnam’s Connecticut Militia in 1755; acting as a recruiter for John Winslow’s militia in Portsmouth, New Hampshire; taking the initiative in mustering, equipping, and commanding ranger units; being personally responsible for paying his soldiers, and going deeply into debt as a consequence after taking loans to ensure that they were properly paid (their regular pay was stolen during an ambush on a British transport to Fort Edward); was the indispensable cutting edge of the British army in the northern sector around Crown Point; led a force of two hundred rangers on an expedition far behind enemy lines to the west against the Abenakis at Saint-Francis near Quebec, a staging base for Indian raids into New England; capturing Detroit in 1760; accepting the submission of the French posts on the Great Lakes during the spring of 1761; occupying Fort Michilimackinac and Fort St. Joseph; being transferred to North Carolina to pacify the Cherokees; fighting determinedly at the Battle of Bloody Run to put an end of Pontiac’s Rebellion in 1763; publishing his A Concise Account of North America in 1765 and co-authoring a stage-play, Ponteach [Pontiac]: or the Savages of America, in 1766; and being appointed by King George’s third governor of Michilimackinac (now Mackinaw City) through a royal charter to seek out the Northwest Passage.

This is a creditable curriculum vitae, one might think, but one somewhat tarnished by a youthful flirtation with a gang of counterfeiters in 1754; accusations of administrative malfeasance and high treason while governor at Michilimackinac; periods of exile in England; claims that he may have exaggerated in his journals; time spent in a debtors’ prison; initial ambiguity over his loyalties and role at the time of the outbreak of the American War for Independence; involvement in the subterfuge surrounding the capture of the spy Nathaniel Hale; arousing the enmity of George Washington, with the first President admitting “Rogers was the only man [I] was afraid of”; escaping from Patriot prisons; suggestions of spousal abuse in the divorce petition submitted by his wife Elizabeth Brown in the late 1770s; two short and unsuccessful stints as leader of the Queen’s Rangers in 1776, and later the King’s Rangers in 1779; and a long history of habitual alcoholism. Rogers eventually retired on grounds of “ill-health,” no doubt precipitated by licentious behavior, resulting in the Great Major dying in drunken obscurity in London’s Southwark stews in 1795.

This was a colorful life, indeed, and one that in the view of this writer demonstrates that Rogers was displaying all the signs of what we now recognize as post-traumatic stress disorder, a condition which was no doubt amplified by his lack of good breeding, the class system which permeated the British military cadre, and the innate and arrogant anti-colonial prejudice that he had to overcome. He was in fact one of the very first legends of colonial folklore who was wrongly cast aside, both by the British and his fellow Americans, until, in the words of Guy Chet from the University of North Texas, he was rediscovered in the form of “the Americanized warrior that’s a product of the nineteenth century,” explaining that it was made possible by “the same cultural forces that made The Last of the Mohicans such a literary hit and it resurrected Robert Rogers from oblivion.”

Efforts to resuscitate Rogers include military artist Thomas Davies’ painting, The View of the Lines at Lake George, dating from the mid-1750s, which is the earliest known representation of the area in question and depicts a ranger standing by the Lakeside; and Benjamin West’s iconic 1770 neo-classical painting, The Death of General Wolfe, featuring the fanciful image of a ranger at the prostrate general’s side at Quebec. Chet correctly asserts that with Francis Parkman’s championing of the Major and Frederick S. Remington’s illustrations (like those showing the scouting expeditions around Fort Carillon and the Battle on Snowshoes), Rogers’ stature was restored by the mid-nineteenth century to that of a hero, even if a flawed one. Parkman (1823-1893), author of the monumental seven-volume France and England in North America and trustee of the Boston Athenaeum (who, due to his foresight, holds the largest collection of Confederate imprints anywhere) from 1858 until his death, wrote extensively in his very literary histories of the Rangers’ reconnaissance missions in the wilds of upper New York State:

The forest was everywhere, rolled over hill and valley in billows of interminable green, – a leafy maze, a mystery of shade, a universal hiding place, where murder might lurk unseen at the victim’s side, and nature seemed formed to nurse the mind with wild and dark imaginings. The detail of blood is set down in the untutored words of those who saw and felt it. But there was a suffering that had no record, – the mortal fear of women and children in the solitude of their wilderness homes, haunted, waking and sleeping, with nightmares of horror that were but the forecast of an imminent reality.

And:

Eight officers and more than a hundred rangers lay dead and wounded in the snow. Evening was near and the forest was darkening fast, when the few surviving broke and fled. Rogers with about twenty followers escaped up the mountain; and getting others about him, made a running fight against the Indian pursuers, reached Lake George, not without fresh losses, and after two days of misery regained Fort Edward with the remnant of his band. The enemy on their part suffered heavily, the chief loss falling on the Indians; who to avenge themselves, murdered all the wounded and nearly all the prisoners, and tying Phillips and his men to the trees hacked them to pieces.

Parkman is now, of course, considered a reactionary and a racist and is the subject of increasingly vitriolic criticism. Historians like C. Vann Woodward object to his views on nationality and race, writing witheringly that Parkman had “permitted his bias to control his judgment, employed the trope of ‘national character’ to color sketches of French and English, and drew a distinction between Indian ‘savagery’ and settler ‘civilization.’”

Robert Rogers, a white male American capable of beating the Indians at their own game, was to suffer the same fate, and his reputation and successes, as we shall see, needed to be deconstructed. Van Woodward’s concerns were shared by the French-trained historian W. J. Eccles, who insisted that Parkman was also biased against France and Roman Catholicism in general, and although “La Salle and the Discovery of the Great West (Boston, 1869) is doubtless a great literary work . . . as history, it is, to say the least, of dubious merit.” However, no such recognition regarding style or fluid narrative is afforded Parkman by much more stridently Leftist historians like Francis Jennings, who deride the Boston Brahmin in much the same way the Dunning School of historians are patronized by later and more radical authors and researchers of the American Civil War and Reconstruction. For them, Parkman is a fabricator and an apologist for colonialism and the ethnocide of the First Peoples. Rogers himself is made out to be the very personification of evil.

But is this a fair assessment of Parkman, or indeed Rogers? Certainly, more balanced views do exist, with historians like Robert S. Allen saying that Parkman’s history of France and England in North America “remains a rich mixture of history and literature which few contemporary scholars can hope to emulate.” The historian Michael N. McConnell, while acknowledging the historical errors and racial prejudice in Parkman’s book The Conspiracy of Pontiac, has written:

. . . it would be easy to dismiss Pontiac as a curious – perhaps embarrassing – artifact of another time and place. Yet Parkman’s work represents a pioneering effort; in several ways he anticipated the kind of frontier history now taken for granted. . . . Parkman’s masterful and evocative use of language remains his most enduring and instructive legacy.

And the American literary critic, Edmund Wilson, in his book O Canada, descried Parkman’s France and England in North America in his book O Canada in the following terms: “The clarity, the momentum and the color of the first volumes of Parkman’s narrative are among the most brilliant achievements of the writing of history as an art.”

And do the hackneyed claims of racism and sexism justify the partial erasure and continued denigration of his main American antagonist, Robert Rogers, from the historical record? For Parkman’s Rogers not only left traces in James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, but also in Kenneth Roberts’ Northwest Passage. Cooper’s The Pathfinder opens with one of the most beautiful and evocative descriptions of America’s inland sea to be found anywhere in literature:

And truly the scene was of a nature deeply to impress the imagination of the beholder. Towards the west, in which direction the faces of the party were turned, the eye ranged over an ocean of leaves, glorious and rich in the varied and lively verdure of a generous vegetation, and shaded by the luxuriant tints which belong to the forty-second latitude. The elm with its graceful and weeping top, the rich varieties of maple, most of the noble oaks of the American forest, with the broadleaved linden known in the parlance of the country as the basswood, mingled their uppermost branches, forming one broad and seemingly interminable carpet of foliage which stretched away towards the setting sun, until it bounded the horizon, by blending with the clouds, as the waves and the sky meet at the base of the vault of heaven. Here and there, by some accident of the tempests, or by a caprice of nature, a trifling opening among these giant members of the forest permitted an inferior tree to struggle upward towards the light, and to lift its modest head nearly to a level with the surrounding surface of the verdure. Of this class were the birch, a tree of some account in regions less favored, the quivering aspen, various generous nut-woods, and divers others, which resembled the ignoble and vulgar, thrown by circumstances into the presence of the stately and great. Here and there, too, the tall straight trunk of the pine pierced the vast field, rising high above it, like some grand monument reared by art on a plain of leaves.

It was the vastness of the view, the nearly unbroken surface of verdure, that contained the principle of grandeur. The beauty was to be traced in the delicate tints, relieved by graduations of light and shade; while the solemn repose induced the feeling allied to awe.

Such a portrayal of the boreal north is only matched in the artwork of the mid-nineteenth century Hudson River School, whose aesthetic visions of the Catskill, Adirondack, and White mountains were heavily influenced by the Düsseldorf School of painting and the Romantic movement. Artists like Thomas Cole, Albert Bierstadt, Asher Durand, and Frederic Edwin Church, being conscious purveyors of themes of nationalism, nature, and property, reflect three themes of America in the nineteenth century: discovery, exploration, and settlement, and rightfully suspicious of the economic and technological development of the age. This is not unlike Fenimore Cooper’s The Prairie, which ends thus:

The trapper had remained nearly motionless for an hour. His eyes, alone, had occasionally opened and shut. When opened his gaze seemed fastened on the clouds which hung around the western horizon, reflecting the bright colors and giving form and loveliness to the glorious tints of an American sunset . . . For a moment, he looked about him, as if to invite all in presence to listen, (the lingering remnant of human frailty) and then, with a fine military elevation of the head, and with a voice that might be heard in every part of that numerous assembly he pronounced the word – “Here!” . . . The grave was made beneath the shade of some noble oaks. It has been carefully watched over to the present hour by the Pawnees of the Loup, and is often shown, to the traveler and the trader, as a spot where a just white-man sleeps. In due time the stone was placed at its head, with the simple inscription, which the trapper had himself requested. The only liberty taken by Middleton, was to add, “May no wanton hand ever disturb his remains.”

This is a fictional soliloquy which might be appropriate for Rogers himself.

For the central character of Kenneth Robert’s Northwest Passage, a book first serialized in the Saturday Evening Post and which was the second bestselling novel of its day, bettered only by Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind, was a sort of American Homeric Odyssey, the opening excerpt beautifully fore-shadowing what was to follow:

The Northwest Passage, in the imagination of all free people, is a short cut to fame, fortune and romance – a hidden route to Golconda and the mystic East. On every side of us are men who hunt perpetually for their personal Northwest Passage, too often sacrificing health, strength and life itself to the search; and who shall say they are not happier in their vain but hopeful quest than wiser, duller folk who sit at home, venturing nothing and, with sour laughs, deriding the seekers for that fabled thoroughfare – that panacea for all afflictions of a humdrum world.

What a better way to describe an adventurer like Robert Rogers, encapsulating both the excitement and the pathos of a life lived to the full? Roberts’ narrative, greatly aided by the skillful editing of Booth Tarkington, tells the story of the Raid on St. Francis, including descriptions like:

“How’d it happen the Indians never caught him?” Hunk asked. McNott put his elbows on the table and glanced quickly over his shoulder. “By God,” he said, “I dunno! I dunno how he does it! He’s the size of a moose, but he goes drifting through the woods like an owl. He’ll stand right in plain sight, in the middle of some trees, and if you take your eyes off him for a second, he aint there. No sir: you can look for him all day, and you can’t find him! The Indians, they call him a devil. White Devil. That’s their name for him: Wobi madaondo: White Devil. They say he disappears into rocks, and pops out of ‘em, like Pamola, the Evil One.” . . .

To the Sergeant’s way of thinking , the Major was the greatest man and the greatest soldier the world had ever seen . . . McNott, it appeared, had lived most of his life in Dunbarton, and so too had Rogers, except during those periods when the French-led St Francis Indians, coming down from the north, had burned the farmhouses, destroyed the crops, slaughtered the cattle, chopped down the fruit trees, scalped settlers and stolen women and children, and so forced farmers to seek sanctuary in block-houses in the larger settlements . . . ”Why,” McNott said, “seems like Rogers begun to chase Indians before he was weaned! Fifteen years old, he was, when he started fighting ‘em; and in a year’s time the smartest Indian ever made couldn’t think half as much like an Indian as Rogers could. He knew what they aimed to do before they knew themselves; and from that day to this, he ain’t changed one damned bit. No, sir! He hates a St Francis Indian worse’n poison . . .”

And:

Beyond him, from the ravine, I heard an awful sound – a thin, high squeal, made by a man. I heard yells, half-howl and half-caterwaul, that made the skin move behind the ears, as at the shriek of a lynx. When I reached Avery, he snapped up the lock of my musket and knocked the powder from the pan so it couldn’t be fired. The whole bottom of the ravine became clearer to me. Upstream and downstream, in two scattered groups, were Indians crouched behind the boulders: lying behind fallen tree-trunks. They were painted black and vermilion. Those rushing down the bank, and stumbling jerkily at the edge of the stream, were Dunbar’s, Turner’s and Jenkins’ men. Rushing with them and darting among them were other black-painted Indians and a horde of small men – Frenchmen – in a brighter green than the greenish buckskins of the Rangers. There must have been two hundred Frenchmen and Indians. If one of the stumblers broke loose from those around him and started upstream or downstream, a hidden Indian rose from behind a boulder and sank a hatchet in him. I made out Dunbar, standing at the edge of the water, defending himself, with his bayoneted musket against three Frenchmen. Seemingly the powder was wet; for not a musket was fired. An Indian came out of the foaming water behind Dunbar, split his head with a hatchet, and leaped forward on him as he fell. He knelt on Dunbar with one knee and chopped off his head. From the struggling, confused throng came agonized cries that made me sweat and shake. I saw two Indians, upstream, holding down a Ranger, head and foot, while a third Indian dismembered him with a hatchet, although he was still alive and screaming.

The Atlantic Monthly declared the novel “a great historical document, which historians will acclaim,” while The New Republic endorsed its vision of the past for “anyone interested in the making of the nation.” The movie version, starring Spencer Tracy, was treated in a similarly positive manner. When the film was released in the US, the Department of Secondary Teachers of the National Education Association recommended Northwest Passage for classroom use, because “the success of this hardy band of early pioneers symbolizes our own struggles against bitter enemies in the modern world.” The film scholar Jacquelyn Kilpatrick pointed out that another teacher’s guide had endorsed the film for explaining everything from geography to art (one of the Rangers painted and killed Abenakis), claiming that through the “fine assortment of types” among the minor characters, “we glimpse early American characteristics of which we are rightly proud.”

These are sentiments that are countered by the likes of Randolph Lewis, in his critique of the book and movie in his article “Classic,” where he writes:

Given the treatment of Native peoples in popular culture even until recent decades, the Abenakis were better off without the attention of the screenwriters and directors . . . Their good fortune, such as it was, was shattered in 1940. As Hitler’s tanks raced across Europe and Japanese pilots trained for their raid on Pearl Harbor, MGM studios set their sights on an older foe, one whose on-screen defeat would remind European-Americans of their ability to crush even the most “bloodthirsty” enemies of progress and civilization. Only months before the Nazi and Japanese armies were confirmed as the new “savage Other” for European-Americans on which to set their sights, Hollywood turned its Technicolor gaze on the original Other, focusing on a tribe that escaped its notice in the past. In the hit movie Northwest Passage (1940), the Abenaki people became the sudden target of one of the most racist films ever released. If less notorious than nasty screeds like Birth of a Nation or The Searchers, Northwest Passage deserves recognition as their ideological equivalent, and should be treated as a black mark on the career of its director, the generally progressive King Vidor. . . .

Northwest Passage starred Spencer Tracy as the colonial military leader Robert Rogers (1731-1795), whose “Rangers” had burned the Abenaki settlement of Odanak, in 1759. During the Seven Years War, Rogers’s men were supposed to serve as faux Indians after most of the real ones sided with the French, but instead of mastering the art of woodlands warfare and passing stealthily into symbolic redness, most of them were no match for highly skilled French marines or Native warriors who engaged them in the forests of New England. That Rogers ever became an Anglo-American hero is a tribute to the power of cultural mythologies to displace and dominate the historical record – as one historian has tartly observed, “What Rogers lacked as an irregular, he made up as self-publicist.” His boastful and inaccurate Journals became a literary sensation in London in the mid-1760s, obscuring the real facts of his “adventures” with self-aggrandizing half-truths that did not quite conceal the grim realities on which they were based. Here is how Rogers described the fateful morning of October 4, 1759:

“At half hour before sunrise I surprised the town when they were all fast asleep, on the right, left, and center, which was done with so much alacrity by both the officers and men that the enemy had not time to recover themselves, or take arms for their own defense, till they were chiefly destroyed except some few of them who took to the water. About forty of my people pursued them, who destroyed such as attempted to make their escape that way, and sunk both them and their boats. A little after sunrise I set fire to all their houses except three in which there was corn that I reserved for the use of the party. The fire consumed many of the Indians who had concealed themselves in the cellars and lofts of their houses.”

Somehow, this massacre of semi-combatants and non-combatants became a defining event for Anglo-American culture in both the US and Canada, and over the centuries, as Rogers was wrapped in layer after layer of hagiographic gauze, he became an ideal subject for a Technicolor epic. Yet because Hollywood producers do not read obscure primary documents, Rogers’s leap to cinematic prominence required the intermediate step of a best-selling novel, which Kenneth Roberts penned in 1936. In crafting his “historical” narrative of the raid, Roberts expended little effort in disentangling Rogers’s mélange of fact and fancy, which did not keep the book from being treated as a factual account. This was true not only in undistinguished newspapers, but also in the so-called serious press. As the book sat atop the best-seller list for almost two years . . . Despite the unsavory nature of Roberts’s narrative, MGM was quick to capitalize on the success of Roberts’s novel, lining up a respected director (Vidor) and an A-list star (Tracy) to begin production in 1939. Ignoring the quest of a “northwest passage” that consumed much of the novel, the film version focuses on the raid on Odanak and the glorification of Major Roberts. In a green-fringed Robin Hood get-up that would let him pass as “Indian” in the cold forests of New England, Spencer Tracy’s Rogers is one of the early white protagonists who is even more Native than the Natives. One of his men brags that, “The smartest Indian alive can’t think half as much like an Indian like Major Rogers can,” though the filmmakers’ judgment about “Indian thinking” seems clouded when we see the Abenakis depicted in the movie with an absurd trampoline-sized drum. The movie is filled with such inaccuracies, yet one aspect of the original event does filter through even the gauzy lens of Hollywood: the brutality of the raid, even in a film with a celebratory point of view, still seems far from heroic.

Northwest Passage is one of those rare texts in which everything was laid bare without anyone meaning to do so, thereby allowing the secret history of colonialism to seep through the celluloid and compete for recognition with the “official version” the filmmakers intended to honor – which is to say, the text is easily inverted. For example, the film is drenched with extreme expressions of bloodlust on the part of the colonists that might seem like warrior machismo on one light, but mental illness in another. Explaining to new recruits that his men eat like kings when prowling the North woods in their green stockings, Major Rogers declares, “Of course, now or then they have to stop eating to kill and Indian or two.” Perversely, one of his men even combines the two activities, wrapping the head of a slaughtered warrior in a leather bag and then gnawing on pieces of it to curb his hunger. He even shares bits of the head with fellow Rangers (who, to be fair, do not realize what he is feeding them) . . . Perhaps because of the cannibalism and various scenes of orgiastic killing inflicted upon Abenaki people, Northwest Passage takes great pains to legitimize their slaughter through didactic speeches and asides . . . In Vidor’s film, there’s a symbolic link between “historical”, “barbaric” Abenaki violence and contemporary Fascist aggression overseas, one that is more than a product of an overheated imagination or a presentist orientation to the past . . . The Abenaki writer Joseph Bruchac saw Northwest Passage as a young boy in upstate New York, and he still remembers the trauma of hearing some of the final words of the film: “Sir, I have the honor to report that the Abenakis are destroyed,” Major Rogers tells his delighted superiors. While the rest of the audience cheered these words, young Bruchac sat silent in the theater, suddenly fearful. “That movie had made me afraid.”

The popularity of Northwest Passage suggests a great deal about the general culture of Indian-hating in which Native youth grew up in the 1940s, as well as the specific degradation of Abenaki culture that they were forced to witness all around them. “In hindsight, we can easily say that the native people of North America were oppressed by three major forces,” Chief Leonard George, a First Nations leader, recently said. “There were the government, religion, and Hollywood…” Celebrated as a Hollywood “classic,” Northwest Passage weds this oppression to cinematic “art.”

The merits and demerits of Rogers and what he has come to symbolize are revisited every time the illustrations by artists like Ron Embleton and Gary Zaboly are displayed or discussed; every time Christopher Shaw’s The Battle on Snowshoes, from his 2000 recording Adirondack Serenade is sung; and whenever reruns of the 1958-59 NBC TV show starring Buddy Ebsen and Keith Larsen, or the more recent AMC drama Turn: Washington’s Spies, is syndicated. One wonders how long Methuen High School, where Rogers was born and raised, will continue to use the “Rangers” as their mascot, and for how much longer will Rogers’ statue, commemorating both the man himself and his Rangers, stand tall on Rogers’ Island, where a substantive archaeological excavation has taken place to uncover colonial artifacts, will remain intact. Or will it, too, fall to the victim mythology that has led to frenzied attacks on the statues of Southern heroes? This would be followed, of course, by the predictable and outrageous demands for reparations, books being taken off library shelves, and artwork being vandalized by agents of hysterical minorities fighting back against the supposed atrocities of white colonialism.

Perhaps the final paragraph from Roberts’ Northwest Passage text should inform – and in some way define – our collective response:

And then Ann surprised us all. “Dead?” she said softly. “Rid of him? He’ll never die, and you’ll never want to be rid of him and what he stood for!”

She rose, crossed the room and slid aside the shutter. The wind of late October rattled the windows, and we heard the scurry of dry leaves whirling against the door with the sound of moccasined feet running across frosty grass. A bellowing squall plucked at the corner of the house.

“That sounds like his voice,” Ann whispered; “his voice and his footsteps, searching, hurrying, hunting! Ah, no! You can’t kill what was in that man!”