Coen? No, Caan:

Reflections on Slither

Posted By

James J. O'Meara

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

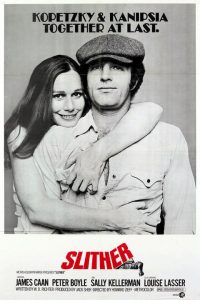

Slither (1973)

Directed by Howard Zieff

Screenplay by W. D. Richter

Starring James Caan, Peter Boyle, Sally Kellerman, Louise Lasser, Allen Garfield, Richard B. Shull, & Alex Rocco

“What the f*** am I doing here in a vegetable stand in the middle of nowhere?”

TCM recently held an Ed Begley night,[1] [2] and first up was Rod Serling’s Patterns, which I’ve talked about here before [3], and I was looking forward to seeing it in a good, cleaned-up print, unlike the muddy, deteriorating mess the local government-owned channel had unreeled. And it was indeed a pleasure to watch again, but the real surprise was what had been programmed in the preceding timeslot: Slither, a movie I have vaguely heard of now and then since it came out in my teens.

I never saw it, until now, but for some reason it had stuck in my mind all these years; was it an ad, or a preview [4] I saw back then? Without an Internet, and sites like IMDB, or DVDs (when did videocassettes arrive?), not to mention the film itself apparently disappearing without making much of an impact, I had only rumors and hints to go on, picked up by accident now and then, like a heroic journalist piecing together a vast conspiracy.

And not doing a very good job of it. I had formed the notion that it was an early Robert Altman film, and involved ordinary folks innocently swept up in in the fallout from some vast criminal or political caper. The one frequently occurring reference – and thus far the only accurate one – was their being pursued by a sinister black van, the nature of which was never revealed.

I can only assume that my impressionable young mind, lacking any accurate information, had mashed together various tenuous connections to films of the same era: Sally Kellerman must have suggested Altman (M*A*S*H, 1970), Peter Boyle the sinister conspiracy (The Conversation, 1974), and so on. Perhaps it was a sort of icon of the zeitgeist?

As it turned out, the film was a revelation. Actually, it’s kind of a small-scale, auteurish version of the big-budget, established-star-filled It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (1963). IMDB says [5]:

While searching for a small fortune of embezzled money, an ex-con, a small-time bandleader, his doting wife, and a kooky drifter find themselves being followed. Their chase takes them to trailer camps, bingo halls, laundromats, and ultimately, a showdown with a group of unconventional bad guys.

First off, it’s an absolutely beautiful film, and it wasn’t until the end credits that I learned why: László Kovács! The great ex-Hungarian cinematographer, who photographed every great film of the ‘70s-‘80s that Vilmos Sigmond didn’t.[2] [6]

Thanks to Kovács, it has that lovely, autumnal, “golden hour” look common to the films made during that second Hollywood Golden Age, when serious, small films for adults were all over the place; the time before Jaws and Star Wars convinced Hollywood that the future lay with big explosions.[3] [7]

Coincidence, correlation, cause, conspiracy? The high point of American cinema and Whiteworld took place almost simultaneously.

The cast. My God, the cast! How can you not love to see all these people on screen together?

Another small pleasure of such films is the archaic, lost technologies on display. Boyle’s washed-up big band musician (and big bands themselves were dying out in the post-war era) has transferred all his rare 78s to tape . . . eight-track tape. Kellerman sends Caan to a diner bathroom to obtain a condom from the coin-operated machine therein (I haven’t seen one of those since my college days, although one did figure in an episode of Bottom). Garfield looks for a forwarding address for endless, awkward moments in a small card file balanced precariously on his knee – a Rolodex would blow his mind!

I’m not sure it counts as technology, but the two “sinister” black vans (actually, 1972 Dodge motorhomes [8], apparently) are customized, non-functional monstrosities that look like something a 13-year-old boy would come up with after seeing Mad Max, or those head cameras [9] in Albert Brooks’ Real Life (1979).

And yet, as the film reminds us, this is the cutting edge of Western civilization: Boyle’s Airstream trailer is government surplus, having been used to quarantine the astronauts after the Moon landing.

Speaking of the Moon landing, perhaps the most striking thing about the film, for people like us, is how gosh-darn white it is. At a certain point, I started to notice that the only black characters were menial employees scurrying around in the background of some downtown scenes. The diner scene has one black in a speaking role, to whom Caan whitesplains why he shouldn’t try to use his rifle to stop Kellerman’s robbery.

Mostly, this homogeneity is baked in, since the movie takes place in small California towns (in the ‘70s, of course), and mostly on the road in the aforesaid Airstream, stopping from time to time in various “travel lodges” – more lost technology; do they still exist, now that everyone flies? – where the only entertainment is barbequing and bingo.

In most any modern film, these roles with be reversed, with the white deplorables pushed to the background, while heroic blacks cure the vampire virus, defeat the aliens or, in “non-fiction” films, make the Moon landing possible with their mad calculatin’ skillz.

If the film did focus on whites, they would be alternately rock-stupid or homicidal; not, as here, intelligent but charmingly misguided (Kellerman is always wonderful as she offers her unsolicited life advice and explanations of what’s going on).

Which is odd, since the director, Howard Zieff, who died only recently at 81, seems to have been a pioneer of the PC casting fad. This looks to be the first in a rather small body of film work, including Streisand’s The Main Event, Goldie Hawn’s Private Benjamin, and Walter Matthau’s House Calls; middlebrow Judaica. But his main claim to fame was as a commercial director – that is to say, a director of commercials. IMDB says [10]:

Howard Zieff’s early ad campaigns were noted for their innovative casting. Breaking from the stereotypical blond-haired, blue-eyed, old Hollywood ideal of perfection, he cast young unknowns with decidedly ethnic, un-Hollywood features, including Robert De Niro, Dustin Hoffman and Richard Dreyfuss.

Before going into the movies, he was responsible for many memorable advertising campaigns. Most memorable was the Alka-Seltzer “Spicy Meatball” commercial [11] in which an actor must work through repeated takes for a tomato sauce.

They then offer this “personal quote”:

On photographing in 1967 for the “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levy’s [12]” ad campaign: “We wanted normal-looking people, not blond, perfectly proportioned models. I saw the Indian on the street; he was an engineer for the New York Central. The Chinese guy worked in a restaurant near my Midtown Manhattan office. And the kid we found in Harlem. They all had great faces, interesting faces, expressive faces.”

Well, this cast certainly has interesting faces. One thing that really struck me – or stuck out, if you will – is how big the women’s teeth were. I mean, Louise Lasser was always known for her huge choppers, but for the first time I noticed how big Kellerman’s are.[4] [13] Her teeth, I mean. But leaving that possibly Freudian observation aside, Kellerman does put that face to work, successfully conveying, in the diner scene [14], that sequence of moments when your date moves from sexy, to seductive but a little nutty, to full-blown homicidal maniac, à la Juliette Lewis.

But back to ethnicity. Lasser and Kellerman are both Jews – both Russian Jews, I discover. (Does that explain the teeth?) So is James Caan, but all three have made careers playing goyim; most people seem to think Caan is Italian, what with his most famous role being Sonny Corleone.[5] [15]

As for Boyle, IMDB [16] says:

His paternal grandparents were Irish immigrants, and his mother was of mostly French and British Isles descent. Following a solid Catholic upbringing (he attended a Catholic high school), Peter was a sensitive youth and joined the Christian Brothers religious order at one point while attending La Salle University in Philadelphia. He left the monastery after only a few years when he “lost” his calling.

He moved to New York and converted to Judaism. . . . No, I mean, studied acting under “guru” Uta Hagen; same thing.[6] [17]

Interestingly, Boyle, the only goy of the bunch, was quite the SJW; IMDB again:

Peter’s breakout film role did not come without controversy as the hateful, hardhat-donning bigot-turned-murderer Joe (1970) in a tense, violence-prone film directed by John G. Avildsen. The role led to major notoriety, however, and some daunting supporting parts in T. R. Baskin (1971), Slither (1973) and as Robert Redford’s calculating campaign manager in The Candidate (1972). During this time his political radicalism found a visible platform [yeah, like we couldn’t tell from his “goyim are violent and corrupt” roles] after joining Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland on anti-war crusades, which would include the anti-establishment picture Steelyard Blues (1973). This period also saw the forging of a strong friendship with former Beatle John Lennon.

While Caan seems to be pretty based:

I was never politically oriented – in fact I called myself a radical middle-of-the-roader. Unfortunately, with these last two terms of our current president, my children are going to be affected by his decisions, or lack of them, in a big way.

It’s a pretty dangerous world, so given the choices – which are not really wonderful – I am supporting Donald Trump in the hopes that his ego won’t get in the way, and that he’s smart enough to hire good people. We don’t know that, but we pretty much do know what Hillary will do. So if Trump listens to the people he hires and he has a great cabinet, the scale tips that way for me. We need a hawk right now.[7] [18]

Well, there is that JudeoCon touch about “listening to the right people,” but still rather out there for a Hollywood guy.

Allen Garfield, on the other hand, plays, as per usual, a schlubby, vaguely Jewish small-time crook [19].[8] [20] IMDB clues us in [21]:

New Jersey-born Allen Garfield was trained at the Actors Studio in New York City. He had a prolific career on the stage before making his film debut in 1968. His stocky build and nervous, jumpy mannerisms fit well with the weaselly criminals, lecherous villains and corrupt businessmen and politicians he excels in playing – a perfect example of which is the Beverly Hills police chief in 1987’s Beverly Hills Cop II (1987). Midway through his career he reverted to his real name of Allan Goorwitz, but not long afterwards decided to stay with his stage name, and went back to Allen Garfield. In the early 2000s, Garfield suffered from a series of strokes that prevented him from acting again.

There are a lot of Jews in California, of course, but he really looks out of his element in small-town Stockton. He’s what “Grammy Hall would call a Real New York Jew [22].” We find him in his run-down office, which seems to have been disassembled in New York and rebuilt for him here, and eating what seems like a stereotypically New York lunch—some kinda sandwich, like pastrami, with a giant pickle and a cream soda. The big joke here is that ultimately the bad guys turn out to be him and his brothers, who all share the same vaguely schlubby New York tax-preparer look, right down to the big glasses and green short-sleeve shirts, and they stick out unassimilably in the crowd at the trailer park bingo game.[9] [23]

So whatever the director’s predilections, we are still at a moment in Hollywood when Jews can be the bad guys, and white folks are kooky and laughable but endearably human for all that; not the crazy, treacherous, world-dominating bigots of today’s entertainment world.[10] [24]

It’s a Ghost and Mr. Chicken world, which won’t change until Mel Brooks rolls out Blazing Saddles.[11] [25]

Of course, the real question is, is it any good? Yes, it is. It’s certainly worth a couple of hours at basic cable prices. It’s like the first draft of a Coen Bros. movie, and you can’t convince me that they haven’t seen it and been influenced by it. Not everything works, but there were a few moments when I did actually laugh out loud at an unexpected bit of lunacy, such as Moe Green bringing ice cream cones back to the black van, and wolfing all three down as he kills time outside with Sonny Corleone;[12] [26] or when Caan runs out of the diner, looks back, and sees Kellerman shooting up the place, off in the distance like an Edward Hopper painting, with little screams and gunfire barely on the soundtrack. (How she turns up later, unscathed and unexplained, is one of many loose ends). There’s even the obligatory vehicular chase, which seems like a parody of the one from Bullitt [27], only with two menacing vans and a house trailer.

Above all, it’s recommended as a beautifully-filmed time capsule of the last time white people ruled the world.

Notes

[1] [28] That’s crusty but benign, as the folks from Network (“The best movie ever,” says [29] Trevor Lynch) would say, Ed Begley, Sr., although his annoying spawn, Ed Begley, Jr., recently decided to dispense with the suffix and go by just plain Ed Begley.

[2] [30] I’ve written about Sigmond, Kovács, and Joseph Mascelli, the three legendary cinematographers, in the context of their early work for the likes of Ray Dennis Stekler and Arch Hall, Sr., in my review [31] of the latter’s cult classic, The Sadist.

[3] [32] See, of course, Peter Biskind, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ‘N Roll Generation Saved Hollywood (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998). “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls is about the 1970s Hollywood, a period of American film known for the production of such films such as The Godfather, The Godfather Part II, Chinatown, Taxi Driver, Jaws, Star Wars, The Exorcist, and The Last Picture Show. The title is taken from films which bookend the era: Easy Rider (1969) [Kovács] and Raging Bull (1980). The book follows Hollywood on the brink of the Vietnam War, when a group of young Hollywood film directors known as the ‘movie brats’ are making their names. It begins in the 1960s and ends in the 1980s.” — Wikipedia [33]

[4] [34] Prowler Needs a Jump says [35], “Another great thing about 70s films is the natural look of the actors. They’re not all shined up with perfect teeth and zero body fat. They look like regular people. They wear bellbottoms and jeans shirts and crappy poly blend sports shirts with white belts. They have average complexions and sticky-outy teeth. Slither has that in spades.” I wouldn’t say that about Kellerman and Lasser, as their teeth seem too perfect, unless that’s what he means by “sticky-outy.”

[5] [36] Alex Rocco played Moe Green, and when he and Caan have a small, comic scene here, it’s like an outtake from an alternate version of The Godfather. Prowler Needs a Jump adds: “Alex Rocco . . . who, by the way, is billed as Man with Ice Cream. Man with Ice Cream! The year before, Rocco was Moe Greene, who was making his bones when you were going out with cheerleaders!”

[6] [37] Hagen’s biography seems to have been, as Miles Mathis would say, “scrubbed”; I can only find references to her “German” birth, but nothing religious or ethnic one way or another. Given her milieu, I would be surprised to find her not to be Jewish; not that there’s anything wrong with that.

[7] [38] “James Caan Believes Trump Makes the US an Offer it Can’t Refuse [39]”: ‘”I’m very pro-Israel, and I can’t like anybody who isn’t,” said Caan, who visited the Kotel, put on tefillin.’

[8] [40] “It’s hard to shine up Allen Garfield . . .” Prowler Needs a Jump, loc. cit [35].

[9] [41] They’re like a combination of future Saul Goodman at the Nebraska Cinnabon, with his earlier bingo-calling shyster.

[10] [42] “But greed alone – and therefore Marxism alone – is not enough to explain the behavior of the media. One can be a gentleman and a patriot and still make money. No, one must also add such elements as alienation from and hostility toward the dominant culture, boundless cynicism, and crazed, hate-filled ethnocentrism to the mix to explain the modern media. In short, one has to add Jews (and their spiritual kinsmen and collaborators).” Trevor Lynch, op. cit. [29]

[11] [43] Jim (Gene Wilder): “You’ve got to remember that these are just simple farmers. These are people of the land. The common clay of the new West. You know . . . morons.”

[12] [44] Vince Gilligan would turn this into a ten-minute silent sequence with Mike and Saul on Better Call Saul.