Con-Tiki:

Torchlight Reflections on an Aryan Archetype

Posted By

James J. O'Meara

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

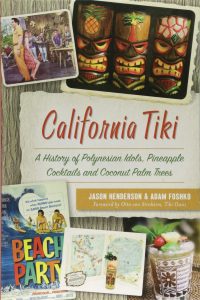

Adam Foshko & Jason Henderson

California Tiki: A History of Polynesian Idols, Pineapple Cocktails and Coconut Palm Trees

Charleston, S.C.: The History Press, 2018

“It’s just a convenient, easily accessible torch. No need to overthink it.”[1] [2]

“You Samoans are all the same,” I told him. “You have no faith in the essential decency of the white man’s culture. . . . I tell you, my man, this is the American Dream in action! We’d be fools not to ride this strange torpedo all the way out to the end.”[2] [3]

Au contraire, mon frere, there is much to think, if not overthink, about the tiki torch and its role in the American Dream, and here’s the book to help us do it.

Perhaps the most enduring image of the infamous Unite the Right march – also known as “Charlottesville,” like some historic Confederate rout – is the tiki torchlight parade. You can see why: on the one hand, a torchlight parade sounds ominous, right out of the Hollywood Nazi playbook; on the other hand, it sounds ridiculous – combined with the polo shirt and khaki wardrobe, it calls to mind the way someone once described the music of Jim Steinman: camp for straight people.[3] [4]

In any event, it was striking enough for Big Tiki to eventually issue the usual press release disclaiming any corporate responsibility for such heinous acts.[4] [5]

Personally, the whole tiki thing seemed to recall nothing but dim memories of scary adult parties in wet, ramshackle suburban patios of distant relatives, and, more recently, occasional ironic hipster references. So when this Kindle showed up on sale, I grabbed an Izod shirt and dug in.

It’s a short read – about a little more than an hour and a half, by my Kindle meter – and it’s well worth your time; it covers a lot of historical and cultural ground in an easygoing manner, even has cocktail recipes, and raises a number of points of interest to White Nationalists.

The book could be – but isn’t – divided into three sections, which I think of as:

- Whence Tiki: Sociological and Cultural Origins

- What’s Tiki: Tiki in Music, Movies and TV

- Whither Tiki: Decline and Rebirth of Tiki

The “economic origins” of Tiki, as the Marxists would say, lay in two enterprising guys: Ernie Gantt (aka “Donn Beach”), onetime bootlegger, now a bar owner in Hollywood, who began using the cheapest liquor available to him – rum – and concocting elaborate and exotic variations on Cantonese food at his eponymous restaurant, Don the Beachcomer; and Victor Burgeron, Jr. (aka “Trader Vic”) in San Francisco, who expanded the drink menu (including the iconic Mai Tai).

But what both men were selling was an idea: “it was this mix of cultures and Seven Seas adventure that really sold the escapist part of the experience. It fueled the fantasy [6].”

These two men had tapped into the rising desire for escape, the need for Americans of the time to be transported somewhere exotic, somewhere exciting – somewhere else. They had also cracked the code of cultivating and packaging that experience in a dark, tropically themed environment, serving sweet and strong exotic cocktails and cuisine about as far away from tuna casserole as the North Pole is from the South.

But why escape? And why Polynesia? For this, we need to look to sociology, and to culture. The American public had been just about primed to go ape over the Tiki experience.[5] [7]

Postwar America was a very different place than any time before or since. The authors estimate that almost ten percent of the American population had served in the Armed Forces.[6] [8] Obviously, not everyone was in combat, but it definitely gave more than a tinge to the subsequent culture.[7] [9]

These returned veterans, especially those who had seen combat, were desperately seeking ways to come to terms with their wartime experiences. The Pacific War had been especially hellish, yet, with a kind of world-historical irony, it had also included experiences of a “lost paradise” of sensual beauty in the Polynesian islands:

As brutal as the fighting had been, this comingling of these two cultures somehow had made the intense fighting, the horrors of war and the rigors of duty more tolerable.

Rather than repressing the horrors of war, Americans could sublimate them in the form of an available Polynesian fantasy:

This was the good life. Easier. Captivating. Alluring. The natives there simply didn’t have the same cares and burdens that Americans had. More to the point, life in the islands was far better than what Americans had seen on the beaches and jungles of Iwo Jima and Bataan – even in the cities of Berlin and Paris, promising a slower pace to living – one of peace, tranquility and endless natural beauty.

But to do that, they would need some kind of model, and that’s where culture comes in (metapolitical theorists take note!).

It all starts, as per usual, with a guy named Thor: in this case, Thor Heyerdahl, a Norwegian Indiana Jones who, to my eye, bears rather a resemblance to Peter Stormare, the Coen Brothers’ go-to guy for menacing white psychos:

Thor Heyerdahl was a Norwegian adventurer and ethnographer with a background in zoology, botany, and geography. He became notable for his Kon-Tiki expedition in 1947, in which he sailed 8,000 km across the Pacific Ocean in a hand-built raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands. (Wikipedia [10])

The subsequent book took America by storm. But:

It wasn’t Heyerdahl’s actual theories of oceanic Polynesian migration that captivated Americans,[8] [11] it was the artfulness of the tale he told – describing his three-month journey and subsequent landing on an island near Tahiti. It was his story that did it. And we were ready to hear it.

It was, as the authors say, “culturally incendiary – igniting the fires of an entire generation.”[9] [12]

But how to fictionalize one’s own experience? The end of the war brought a plethora of novels, writing mostly by veterans who thought they had the chance to be the next Hemingway.[10] [13] But the key work here would be James Michener’s Pulitzer prize-winning Tales of the South Pacific, which also appeared in 1947,[11] [14] based on his experiences – mostly hors de combat – in the New Hebrides:

But unlike other wartime reads, Michener’s book painted an incredibly vivid picture that – very much like Heyerdahl’s story – superseded the reality or even the memory of things, places and events and immortalized them in a tableau of artfully crafted fiction. The result was something greater than itself, something that concentrated and magnified the experiences of the people who went to war – and the Polynesian influences they encountered – and made them readily available to be experienced over and over. Again, it was the story.

In short, a meme, one “reminiscent of the universal idea of a paradise lost and the loss of innocence.” And to propagate the meme? A musical! “Like so many things American, it began with a song . . .”

Now the story that had reached and galvanized so many who had gone off to war – some sixteen million Americans – had been lifted up, sifted, reframed for the stage and infused with a glorious collection of songs. It won ten Tony Awards and a Pulitzer Prize, becoming the second longest running musical on Broadway. It also became the bestselling record of the 1940s.

All of these things together – the return of Americans from World War II, their exposure to the exotic locales of the islands, their intersection with the Polynesian culture, their feelings of having been on an adventure together and shared something that is uniquely theirs, and then having had a romanticized version taken wide and popularized through dramatization and music – created an atmosphere like no other.

The media had allowed the ideas and shared experiences of island life to propagate and intermingle with the American experience – We were hooked.

Tiki was perhaps the first meme, propagated virally through the then-dominant media of fiction and musical theatre.

A key work for the authors’ thesis is The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit, both the novel by Sloan Wilson (1955) and the subsequent 1956 film, starring Gregory Peck:[12] [15]

Tom [the returning veteran] snaps back and forth between then, in the European theater, with its freezing cold tortures interrupted by long periods of romantic dawdling, and the South Pacific, where his service was terrifying and brief, and now, 1955, where he would like to get a better job and maybe a better house.

Tom lives in two worlds, alternating back and forth;[13] [16] this is the motif of Tiki culture: not to run away from the horrors, to “escape” permanently,[14] [17] but to make use of those very elements to construct a good enough modus vivendi within the moderne world:

The great strangeness of Tiki Culture was its aesthetic similarity to some of the most beautiful yet haunting geographies of the war. For Tiki created a popular space where men like Tom, wives like Betsy,[15] [18] women who served as WACS and medical personnel would find entertainment in surroundings that looked like the most vivid moments of their lives. It tamed those lurid memories and turned them into something like a dream.

“Tamed” is the key word here. Rather than repressing or forgetting these experiences, they were sublimated, and turned to practical use: a new, ready-made, easily accessible escape:

Tiki Culture provided a sublimation of the immediacy of death and romance in the war, funneling horror and romance into a kind of ritualized entertainment that could be taken down off the shelf and spun around and then put back.

Rather than “willingly forgetting,” the veterans sought to sublimate their experiences, to control them and transform them into something new. They could easily have pursued a style of chrome and concrete, but they deliberately opted for a world that mirrored their worst nightmares.

Instead of losing oneself in a chrome, midcentury “machine for living,” a veteran like Tom would sublimate elements of the wartime nightmare into a controlled realm of pleasure.[16] [19]

The next section examines the cultural elements that constructed that realm. The first two chapters look at Tiki music in its two forms, Exotica and Surf.

Exotica is the first – and to my mind, the true – musical expression of Tiki:

[It] was intended to be exotic in the true sense of the word – derived from the Greek for outside, incorporating “foreign (or at least strange-sounding)” elements. Musicians of the era took the basic sound of jazz and big band and infused it with sounds that would make the listener – generally assumed to be the suburban American – feel as though they had been transplanted to a foreign land.

Along with rarely-used but familiar Western instruments like bongos or “vibes,” Exotica incorporated gongs, boo bans, steel guitars, and other wind and percussion instruments,[17] [20] as well as Afro-Cuban and Greek rhythms and even bird calls;[18] [21] surely this was the original “world music.”

Thus was produced “the soundtrack to the leisure life of the man in the gray flannel suit as he moved through his retreat paradise.” As such, “Exotica tries to sound like no place real.” And:

Above all else, Exotica was not ironic, not “pseudo-exotic” or pseudo-anything . . . Philip Ford noted that “to complain that . . . Exotica is inauthentic is to miss the point.” It’s authentically exotic, authentically a sound that suggest a place far away.

Yet Exotica was supplanted by Surf, and even today, the music you hear in a Tiki bar is almost certainly Surf. Why?

Surf retains the “sound effect” element; Dick Dale “created the sound that would be defined as surf music when he sought to write songs that would re-create the ratchety, rhythmic sound of water sliding along the underside of a surfboard.” And the surf culture of California, and the newly en-stated Hawaii, was kinda exotic.

Still, Surf, as one of its creators says, “was created by the middle class. The music didn’t come from pain – it came from fun.” The authors add that “[j]ust as [I would say, “while”] Exotica had been an escape from the daily rigors of work and the memories of pain and war, surf was a celebration of a relatively easy life for middle-class white youngsters with time on their hands.”

The authors suggest this was simply a generational shift; Exotica was your parents’ music; surf music was more popular; surf music was more recent. Ultimately, the authors “tend to believe the preeminence of surf music at Tiki bars has more to do with tempo – it’s just peppier. It’s more energetic music, while Exotica tends to be more languid and dreamy, and it may be that visitors to a getaway bar after dinner don’t want to unwind that completely.”

But I suspect the reason has more to do with the two Big A’s: authenticity and appropriation, which the authors do discuss in the Exotica chapter. We’ll return to this when we discuss why Tiki itself disappeared.

Speaking of pep, it’s odd that the authors, though they later address the Tiki revival – complete with capsule reviews of bars and restaurants – fail to even mention one of the more striking examples: Goth Tiki. It certainly refutes their idea that Tiki patrons aren’t looking for a “languid and dreamy” experience. And I’m glad to see that my old hometown is in the forefront; the Detroit Metro Times reports:

Oddly enough, [Tim] Shuller has been a staple in the goth/industrial scene for years, not a genre one normally associates with eye-popping orange Hawaiian shirts. In fact, several years ago the ever-creative Shuller cooked up the idea of a Tiki fetish show. Yes, a Tiki fetish show.

Shuller DJs at the Labyrinth, which regularly hosts Noir Leather’s Hellbound parties, a monthly series of themed fetish shows.[19] [22] Shuller pitched the idea, then used pieces of his collection to accessorize the show – of course, the near-naked model suspended by a spit with an apple crammed in her mouth was a nice touch.

Shuller has collected Tiki for more than 12 years, but his obsession started at the tender age of 6, with a trip to Disneyworld’s Enchanted Tiki Room.

“I was always really fascinated by the whole mood of it, the dark and exotic feel, something that you wouldn’t normally see,” says Shuller.[20] [23]

And, of course, there’s New York’s Otto’s Shrunken Head, a Tiki-themed dive bar with a punk DJ and a room in the back for darker musics.[21] [24]

What Goth Tiki suggests is that the real factor tying these, shall we say, “diverse” musics together lies elsewhere, never to be spoken of; except places like Counter-Currents, which is why you’re here. Your patience will be rewarded when we explore that hidden factor later on.

The authors correctly distinguish true Tiki films, which deal with adult characters facing conflicts between conformity and escape, such as A Summer Place (also from a book by Sloan Wilson), from the derivative “beach movie,” such as Beach Blanket Bingo, which focus on the relatively innocent frolics of teenagers. The Gidget films bring the themes of exotica and surf together: Gidget is into California’s surf culture; her father is one of those poor chaps “forced” to leave Germany by the Nazis and condemned to live in Malibu,[22] [25] while Big Kahuna seeks escape from “that Korea jazz” in his beachfront tiki hut. Several films which merely make use of Tiki themes are also discussed.

An entire chapter is devoted to Elvis’ Hawaiian movies, and legitimately so; although only a few years older than Frankie Avalon, Elvis consistently played adult characters conflicted over family obligations versus fun-fun-fun. While the authors are correct to locate these films in the explosion of interest, stateside, in the new state of Hawaii, they neglect a simpler reason for Elvis’ Hawaiian period: his manager, “Col.” Tom Parker, was an illegal alien without a passport [26]; since he refused to let Elvis out of his sight, Elvis could travel nowhere more exotic than Hollywood, Mexico or, eventually, Hawaii [27].[23] [28] Like his fellow veterans in grey flannel suits, Elvis could only escape into the manufactured Polynesia of Tiki.

The chapter on Tiki TV is a little desperate, as the small screen, monochromatic image, and tinny sound of the era’s sets was poorly suited to fantasy. The authors do have interesting things to say about the detective series Hawaiian Eye, and the medium itself:

Tiki-themed or not, movies always have a sense of the grandiose, so that even dullness can look somehow exciting. The shabby little house that Gregory Peck inhabits in The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit becomes magically shabby.

Television is entirely different – where the movies render the ignoble grand, TV makes the grand intimate. This viewer escapes from the family that likely surrounds him or her and, perhaps unconsciously, joins another family, finding home somewhere else. The man couldn’t [completely] escape, after all, not without condemning his loved ones to misery and himself to disgrace.

Television shows that were heavily tinged with Tiki Culture – Sven Kirsten and others call it “Tiki TV” – made the escape more overt. The viewer still met a recurring cast, a replacement family, but on these shows, the family itself had escaped the industrial life and found itself among palm trees and surf.

A whole slew of TV programs featured men literally disappearing from their stateside lives and reinventing themselves as South Sea adventurers.[24] [29] Wandering, always wandering. What these shows have in common is that the main characters are never tied to a desk. Detectives live like hobos with money, never scrounging, living simply but with plenty of alcohol and good humor. Journalists live like detectives. All lead lives of carefully designed leisure; they love to hate their work and spend all their time on it, flowing from one locale to the next.

However, TV eventually contributes little beyond the late, kitschy parodies of Gilligan’s Island and an ironically legendary Brady Bunch episode:

The castaways were unable to escape to civilization. Instead, they rebuilt it in a Tiki image.

Most people would love two weeks on an island but not the rest of their lives away from family. Plus, what good is a life without antibiotics and modern emergency rooms, a life without schools for the inevitable children to come?

But Gilligan’s Island functions as an ever-recurring dream; the island is always now and always away. The castaways are lost forever, suspended in a waking Tiki torch-lit dream.

The Brady Bunch Tiki-themed episode “by no means brought about, but effectively marks, the end of Tiki Culture.” With all this cultural goodness on display, you will likely be asking, “Hey, wha happa [30]?” The authors briefly toy with the idea that it was just a generation shift, like the move from Exotica to Surf, but correctly find this inadequate. In addition to “the natural replacement of the Greatest Generation with the baby boomers,” they cite “American preoccupation with the Vietnam War” and “a growing interest in ‘authentic’ cultural experiences.”

What would eventually emerge as “Hippie” culture “clashed with Tiki in several specific ways.” No longer satisfied with an occasional weekend escape, total liberation was now demanded: “Soyez réalistes, demandez l’impossible!” In particular, “Free Love” removed the element of danger, even “exoticism,” from sex.[25] [31] The Polynesian elements of Tiki, ironically, no longer symbolized escape from war but rather war itself: an “echo of a theater of war that began to look less romantic every day. Tiki Culture began to seem ‘sinister’ . . . because it looked too much like Vietnam.”

And all this was wrapped up in a third element that seemed to sum up everything else, a new meme: “an imagined simpler, primitive man, and the most salient symbol of the type was the Native American as seen in the popular westerns on television every night.”[26] [32]

In short, (((Woodstock [33]))) happened. As a result, “Tiki and Exotica, which always placed the suburban, white American at its center . . . was vulnerable to accusations of cultural appropriation and racism,” and so became one of the first aspects of American culture to suffer the exterminating wrath of the Cultural Marxists, as we’ve seen most recently in the campaign against Confederate memorials.

As the ’70s turned into the ’80s, many of the Tiki palaces and original artifacts of Tiki had been destroyed: “Completely razed or renovated beyond recognition, Polynesian palaces disappeared without ever having been acknowledged as a unique facet of American pop culture . . . unnoticed and without mourning, a whole tradition vanished.”

“And then, as if it had never been gone, Tiki returned.” But this time:

Tiki offered a different promise and played a different role from its original raison d’être . . employing generic tropical themes but detached from even the imaginary mixed culture of Exotica, removed from the sense of the forbidden world of the other. . . . The visual cues of Tiki would remain, but its cultural salience would continue to drift away.

Originally, Tiki represented a promise of adventure; now, Tiki represents the reclaiming of an American birthright.

Tiki events represent a cultural shift to conventions in honor of pop culture.

Just as the drive-in movie theater is a uniquely American creation, the imaginary version of the South Seas presented in Tiki was a very distinct expression of postwar America.

Now it can be remembered by the contemporary American as the expression of America at a time very much to be admired and wished for. If in the 1950s to have a Tiki bar in one’s house was to wish to escape the present for an idyllic South Seas alternate universe, today the same Tiki bar represents a desire to escape the present for an idyllic 1950s.

The part about the ‘50s sounds a bit alt-righty, but it’s really not about nostalgia for suburban, presumably and deplorably White America at all. The authors don’t press the “cultural appropriation” pedal too heavily – it’s a short book, after all. After quoting a long piece of typically clotted “postmodern” critique of Tiki, the authors wisely reject the call to “address” and “dialogue” with “intersectional and postcolonial issues” of “alternative sexual identities” by observing “that’s not how culture works . . . The observer of Tiki either takes it for its far-ranging borrowing of culture or doesn’t.”

How then to square that circle? As becomes plain in their wrap-up, today’s Tiki responds to those concerns about racism and appropriation in a way that suggests that favorite position of the cuckservative, civic nationalism:

The elements of Tiki were borrowed from other real cultures, and over the years, writers have debated how much to be appalled at the cultural appropriation to be found there.

Tiki Culture borrowed liberally from all of these [Polynesian cultures] and mixed them together, using the “other” as a means of exploring the dreams of Americans.

This is a culture distinctly built around a largely white, largely suburban American community. But fantasy knows no one community. Tiki is always inauthentic except in its capture of dreams, and as recent followers of Tiki have learned, any person can be lost in the hypnotic mix of cocktails, rhythmic music and shadowy, enticing atmosphere. . . .

Tiki is for everyone.

Well, not quite. As we’ve seen, the authors have to struggle throughout with the unbearable whiteness of Tiki culture, “which always placed the suburban, white American at its center.” Even today, you’re as likely to find a non-white face at a Tiki bar as at a country music festival.

Take Tiki music, for example: whether Exotica, or Surf, or – as I suggested above, Goth – what’s common to all these musics is not just “strangeness,” but a particular kind of strangeness: “the result is music that assumes a distinctly Western, American, white ear.”[27] [34] Ah, yes, the White Ear; accompanied no doubt by the White Smirk. In other words, they are implicitly white.[28] [35]

Does this explain the emergence of the tiki torch under the Alt Right brand – just another manifestation of the general resurgence of Tiki culture? Superficially, Tiki may seem to be no more than a reference to a time of white dominance. But that would support the idea that conservatives are literally “reactionaries” who simply want to go back to the supposed “good old days” of their childhood, a kind of chronological conservatism; for Spencer and his Alt Right marchers, back to a supposed time of white hegemony before the damn, dirty hippies ruined everything.

But the reemergence of Tiki belongs to a different dynamic. Tiki taps into essential features of white consciousness; Aryan archetypes, if you will.

Searching the Counter-Currents archives, I’m glad to find that the issue of the iconic status of the tiki torch has already been addressed. In “Forging a New Iconoclasm [36],” Alex Kirillov contrasts two images from Charlottesville, the antifa with his cellphone and the Unite the Right marchers with their tiki torches:

On this note it is important to draw a dialectical comparison between the far left and the far right and how it relates to the authenticity of what a movement is built around. Everyone has seen some photo of the torchlight march of August 11th. In contrast to this compare the image of the antifa member taking a selfie in front of a fire. Both of these images involve the utilization of an object that is a byproduct of modernity. For the torch-bearer it is a tiki torch purchased at Lowe’s, for the antifa it is a cellphone.

The narratives inscribed into both photos can be propositionally exhausted if we talk about them in physical terms, e.g., “These are white men, at night, carrying torches, wearing polo shirts, etc.” “This is an anti-capitalist protester, wearing black, taking a photo in front of a fire, etc.” What’s more important though is that there is a metaphysical component to both of these photos. For the antifa it is the irony of him using a byproduct of the system he claims to detest to capture his moment of “defiance.” . . .

By contrast, the technology being utilized by the rightist (the torch) is not dictating the metaphysical narrative of his photo. The torch is not the contingent aspect of the march photo, if anything is contingent in this sense, i.e., marks it temporally, it is the polo shirts. The photo of the march does not really have a significant ironic narrative necessarily attached to it in the way that the antifa’s does. Instead, the photo captures an ineffable narrative: men who have banded together to defend a historic monument. The question of authenticity in regard to the object has been relinquished as these men participate in a traditional narrative that could have occurred a hundred years ago, or even twelve hundred years ago.

The issue of this ineffability is conjoined to the spirit of Tradition and it is crucial that we take note of the fact that the media is totally incapable of understanding this. . . . It is for these reasons that I see the spirit of Tradition looming at the heart of the Alt Right as a movement and as a people.

It is interesting that Kirilov frames the issue in terms of authenticity, which, as we’ve seen, is a crucial issue for Tiki. The Woodstockers rejected Tiki as inauthentic, while substituting their own inauthentic icons;[29] [37] the antifas are also inauthentic, but so degraded as to delight in it as “ironic, man.” Kirilov finds the marchers, in contrast, to be authentic, but only because he shifts the ground from the tiki torch to the general image of men banding together – the Männerbund, in short.

True enough. But I would argue, further, that the tiki torch itself, though identifiably a construct of the postwar era, is for that very reason – being Tiki – itself archetypally white.

As the authors observe, to accuse Tiki of being “inauthentic” is to miss the point; Tiki is “authentically inauthentic.” It is a deliberate construct that serves as an occasional escape from modernity rather than being, like the hippie’s “back to nature” cult, a phony, because impossible, self-delusion. Tiki is “authentically inauthentic” because, while an unreal fantasy, it is, as Alan Watts liked to say, “rockily practical”:

Tiki Culture provided a sublimation of the immediacy of death and romance in the war, funneling horror and romance into a kind of ritualized entertainment that could be taken down off the shelf and spun around and then put back.

This kind of mechanism is already characteristically Aryan, a kind of Hegelian synthesis of the real and the fantastic, the primitive and the modern, love and death.

The content is distinctively Aryan as well: “an effort to create a visceral, aural, tactile escape to a world that never existed except in their dreams: an island paradise where the pressures of the Gray Flannel Suit and the house-beautiful tyrannies of women’s magazines could be set aside.”

This “island paradise” is, in fact, the original Aryan homeland. But isn’t that homeland supposed to be in the Arctic?[30] [38] What does Aryan Man have to do with these dusky, naked savages of the islands? Indeed, but of course the Arctic Homeland theory presupposes a pre-glacial period when the Arctic was located in temperate climes.

Like the missionaries who deplored the laid-back lifestyle and sexual freedom of the Polynesians,[31] [39] there’s a considerable element on the Right that fetishizes the cold, dark, dismal nature of Northern Europe.[32] [40] Somehow, this is supposed to be “truly Aryan,” and we are to feign nostalgia for some frozen Game of Thrones hellhole, embrace our supposed identity as “Ice People,” shunning bathing, wearing itchy rags, and wolfing down fermented shark “like our ancestors did.”[33] [41]

This was clear to the originators of Esoteric Nazism; Nicholas Goodrick-Clarkes tells us that:

[Himmler’s guru, Karl Maria] Wiligut also provided a further source for the myth of the Black Sun. In one of his Halgarita mottos, a series of cryptic religious revelations written for Himmler in the 1930s, Wiligut described an ancient sun called Santur. Wiligut’s contemporary adepts, Emil Rüdiger and Werner von Bülow, interpreted this heavenly body as a second sun that shone 230,000 years ago upon the Hyperboreans in the North Pole and promoted their spiritual development. Santur still orbits in the vicinity of our planet today as an extinct star, thus invisible, but as a Black Sun it still emits a powerful intelligence.[34] [42]

Nevertheless, isn’t the Southern land of Sun and fun now the anthesis of Aryan man? Esoteric Nazism explains the paradox as well: in Wilhelm Landig’s novel Wolfzeit zum Thule, the character SS Major Eyken expounds thusly:

The North Pole is the theonium of the world, associated with Lucifer, the light-bearer of the north, and Prometheus and represents the spiritual source of all Aryan strength. As its counterpart, the South Pole is the place of greatest materialization and all demonic energies. Using the ying-yang symbol as a model, he indicates that this “white” northern spiritual zone has spawned a “black” point: materialist forces of high finance and Masonic lodges prevail in the United States superpower; the Americans are usurping the Aryans with their own “Thule” base in Greenland; and the Soviets are seeking to develop their own military presence in the Arctic. The Aryans must therefore shift their spiritual potential southward and form a “white” point in the “black” spiritual zone in order to tap its powers for their own purposes in the reclamation of the North.[35] [43] Their goal is the repurified, white sun, the sol invictus of Mithraism, which will ultimately succeed the Black Sun, their present symbol of revanchist military power.[36] [44]

This is Tiki Culture: a beachhead – a “white point” – of Aryan culture, within the American zone (or at least the West Coast thereof), tapping the powers of the Pacific Islands. The American veterans thought they were constructing an escape; actually, they were opening up a second front.

Speaking of mysticism, Tiki has its own mysticism; or rather, it is a manifestation of the archetypal mysticism of the Aryan soul, albeit in fancy foreign dress.[37] [45] As Constant Readers know, I have found the purest, and most modern, expression of this mysticism in the teachings of Neville Goddard.[38] [46]

Indeed, I can now see Neville as very much an expression of Tiki culture; as noted above, he was himself a returning war veteran, and although he never left stateside (or even boot camp), he came by his island affectations (principally, a lilting accent that served him well as a lecturer to postwar audiences yearning for escape) not by “cultural appropriation,” but quite legitimately: he was born and raised in Barbados. Always impeccably dressed, like the Man in the Grey Flannel Suit, and usually accompanied by a mild scent of gin.[39] [47]

More to the point, the “simple method for changing the future” which he taught throughout the Tiki period (he died in 1972) bears considerable resemblance to what the authors cite as the factors “Shuhei Hosokawa identified [as the] three aspects of Exotica:

- Geographically, Exotica focuses specifically on the South Pacific, the “Orient” and on islands in general (rather than on continents and deserts).

- Aesthetically, it is orientated more toward mood and affect than toward structure and thought.

- Epistemologically, it comprises a fantasy of travel, an aural simulation of imagined experience of transport to exotic lands [which is] intended to relax listeners.”

All of which sounds strikingly like Neville’s method: having formed a definite idea of the state you wish to create (i.e., travel to), induce a state of relaxation, create in imagination (fantasy) the feeling (affect or mood) of your fulfilled wish.[40] [48]

In fact, Neville’s frequently retold tale of how his guru, Abdullah, taught him the method strikes all the notes of Tiki Escape; here is how Dan Steele retells it [49]:

Neville’s first experience [50] with it remains one of the clearest explanations. Imagine New York City in winter during the Great Depression. Neville was an out of work dancer. He latches onto an old Ethiopian teacher of kabbalah. For the first time in years, Neville suddenly has an overwhelming desire to visit his home in Barbados. And his teacher, Abdullah, says, “You are in Barbados.”

“Well, no, thank you, I am right here in New York,” thinks Neville. “I am in Barbados?”

“Yes, you are in Barbados, and you went there first class!”

For a penniless bloke in depression era New York, that was quite laughable. But Neville agreed to imagine as he fell asleep that he was in his own bed in his parents’ home in Barbados. And, as I recall, to live in New York with a mind that he was actually in Barbados. New York in November and December bears little resemblance to tropical Barbados. There was something about snow on a sidewalk wider than any palm-lined road on the island that made it hard for Neville to mentally put himself there.

“It isn’t working,” Neville complained.

Abdullah was furious: “We cannot discuss how to get there if you are already there! You are in Barbados, and you went there first class!!” Slam!

And then the check and the tickets came. Unrequested from Barbados.[41] [51] And Neville sailed first class.

I particularly like the “first class” note; talk about white privilege![42] [52]

So, Spencer may have been onto something: a sense of the reemergence of the Aryan mode of thought, though typically, he loused it up in the execution.

Yet, the reemergence of this archetype is too insistent to be derailed by one guy. This week brings news of the latest dark horse for the 2020 Democratic nomination: Tulsi Gabbard. Returning war veteran, check; surfer, check; heritage, half-Polynesian (Samoan), check. She’s not part of the Dissident Right – she’s a Democrat, after all – but she’s anti-nation building in the Middle East and doesn’t kowtow to Israel. As The Daily Beast [53] reports:

Richard Spencer, a white nationalist and alleged domestic abuser who has called for “peaceful ethnic cleansing [54],” has tweeted multiple times in support of Gabbard. David Duke, a former Ku Klux Klan leader and current racist, has also heaped praise upon her.

“Tulsi Gabbard is brave and the kind of person we need in the diplomatic corps,” Spencer tweeted in January 2017. “Tulsi Gabbard 2020,” he tweeted later that year.[43] [55]

Say goodbye to the Alt Right brand; hello (again) to Con Tiki!

Notes

[1] [57] From a discussion on Richard Spencer’s Twitter feed [58]:

Justin Morris @tchsmorris 9 Oct 2017 Replying to @RichardBSpencer

Seriously, though. Why tiki torches?

Hugh Wotmate @wotmeighn 9 Oct 2017

It’s just a convenient, easily accessible torch. No need to overthink it.

[2] [59] Hunter S. Thompson, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (San Francisco: Straight Arrow, 1972), p. 11.

[3] [60] I see that the only reference for this is an earlier article of . . . my own [61]. But I swear I saw it somewhere on the internets.

[4] [62] Sean Czarnecki, “Why Tiki Decided to Douse Torch-Wielding White Supremacists [63],” PRWeekly, August 15, 2017. “Tiki Brand put out a statement this weekend condemning white supremacist marchers who had used its product. It was the second time in three months the company had to disassociate its brand from extremist groups. In May, prominent Alt-Right figure Richard Spencer led a torch-lit march protesting the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville. After that demonstration, Tiki responded to inquiries about the incident on an individual basis, ‘basically reiterating that Tiki Brand products are meant to be enjoyed by friends and family for outdoor gatherings,’ Quintana said via email.”

[5] [64] Someone like Jay Dyer or Miles Mathis can no doubt explain how, to revert to Marxist terminology again, this was “no accident [65].”

[6] [66] “Some 9 percent of the total U.S. population fought in the war – 16.1 million Americans, with 405,000 deaths and 672,000 wounded.”

[7] [67] As I’ve noted before [68], conspiracy researchers tend to make too much of the military family backgrounds of many subsequent Baby Boomer cultural figures; it was quite common to have one or more relatives in the services. I recall an episode of Firing Line where, faced with a Keynesian who claimed the Second World War had increased employment, William F. Buckley replied, “Yeah, I worked in the infantry.” As the authors say, “After Pearl Harbor, every man fit for duty was conscripted for the duration of the conflict.” Even New Thought lecturer Neville Goddard, though a thirtysomething British subject who was married with two children, was drafted. His subsequent early, though honorable, discharge – with full citizenship (service guarantees citizenship, as Heinlein would say) – to perform “valuable wartime employment” delivering metaphysical lectures in Greenwich Village is discussed by Mitch Horowitz in his edition of Neville’s At Your Command; see my review here [69].

[8] [70] Heyerdahl’s “theories” – bearded, white “gods” settled the Polynesian islands – have, of course, become quite un-PC [71]; this is a point to which we shall return.

[9] [72] The authors describe Donn and Trader Vic as “two giants [who] poured rum on the fires of the Tiki revolution – literally using the wood from the Kon Tiki itself – and with Hollywood’s help, set the whole country ablaze.”

[10] [73] In “The Plot Against the Hero [74],” I disputed Colin Wilson’s dismissal of such works as From Here to Eternity or The Caine Mutiny as being somehow “inauthentic” since they deal with individuals adapting to institutions, such as the armed forces. Wilson, who evaded peacetime service by claiming to be homosexual, fails to grasp why these authors felt a need to deal with such socially necessary problems.

[11] [75] Coincidence? Or conspiracy?

[12] [76] Although it’s one of those “8 Films That Remind Us Of ‘Mad Men [77],” it isn’t one of “The 10 Movies ‘Mad Men’ Cast & Crew Were Required To Watch [78],’” oddly enough; especially the little detail that both protagonists accidentally blow up a comrade. The former advises us that “Though ‘Mad Men’ kicks off in 1960 and this film (based on the novel by Sloan Wilson) was set during the 1950s, it’s hard to ignore parallels between Tom Rath (played by Gregory Peck) and Don Draper. Both men are ex-soldiers who are plagued by memories of war and struggle to fit into ‘normal’ society with mixed results. Rath and Draper both commute from their suburban family lives into snazzy Manhattan jobs, leaving behind their beautiful wives (Jennifer Jones plays Mrs. Rath) and TV-obsessed children. And the show knows this too well: Remember when comedian Jimmy Barrett dubbed Don ‘the man in the gray flannel suit’?” Mad Men seems to have strangely ignored the whole Tiki thing; the only sustained reference I can find is the episode “Dark Shadows,” where, according to the Unofficial Mad Men Cookbook blog [79], “Roger woos the Rosenbergs from Monarch Wines with dinner at Trader Vic’s, one of the popular ‘tiki’ restaurants of the era offering faux Polynesian cuisine amid bamboo, flaming torches and drinks served in grotesque goblets meant to invoke tribal totems and deities. Since Roger’s soon-to-be former wife Jane is Jewish, he persuades her to join them (better to make the Jewish connection), but at a price.” The blog goes on to provide some historical background and a recipe: “Trader Vic’s opened in the Savoy-Plaza hotel on the Southeast corner of Central Park, offering ‘exotic cuisine in a tropical setting,’ as New York Times food critic Craig Claiborne described it in 1958. ‘It would be difficult to categorize Trader Vic’s Cuisine under single heading,’ he wrote. ‘It’s a combination of Cantonese, Indonesian and islander cooking, plus a few native American specialties to satisfy less adventurous palates.’ [Note: ‘native American’ in 1958 would, of course, mean native-born white.] Claiborne also mentioned the house specialty Roger suggested to Jane: Crab Rangoon, crabmeat deep fried in a crisp thin shell and served with a hot mustard sauce and a tomato barbeque sauce (see recipe).” Jews, “native” Americans, Cantonese, Indonesians, and “islanders” – even in 1958, Tiki is fraught with ethnic collisions.

[13] [80] Like fellow veteran Kurt Vonnegut’s protagonist in Slaughterhouse Five, he has become “unstuck in time.”

[14] [81] The Twilight Zone episode “A Stop at Willoughby [82],” another influence on Mad Men, dramatizes the inauthentic, futile idea of giving up the Madison Avenue grind by getting off the commuter train at a stop in the 1890s. “That night, he has another argument with his shrewish wife Jane. Selfish, cold and uncaring, she makes him see that he is only a money machine to her. He tells her about his dream and about Willoughby, only to have her ridicule him as being ‘born too late,’ declaring it her ‘miserable tragic error’ to have married a man ‘whose big dream in life is to be Huckleberry Finn.’” — Wikipedia.

[15] [83] Again, a connection to Mad Men.

[16] [84] One might compare and contrast this will the veterans who developed, also in California, the postwar motorcycle culture that, on the one hand, incorporated elements of military life – most notably, Nazi regalia – while simply rejecting modern society as “for squares, man.” See Hunter S. Thompson, Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs (New York: Random House, 1966).

[17] [85] Challenging, as did Carl Orff, the – as I would say – dominance of “romantic” Judaic string instruments.

[18] [86] The authors correctly note that this has little to do with the idea of using instruments to suggest animal sounds, as in Peter and the Wolf or even Messiaen; “these are sound effects that complete the illusion.” Perhaps the closest ancestor to this is Richard Strauss’ use of a wind machine in the instrumentation of his Alpine Symphony.

[19] [87] I discuss dance club theme nights and dress codes as modes of implicit whiteness in “Fashion Tips for the Far-from-Fabulous Right,” reprinted in my collection The Homo & the Negro: Masculinist Meditations on Politics and Popular Culture [88]; ed. Greg Johnson(Second, Embiggened Edition, San Francisco: Counter-Currents, 2017); also relevant is my discussion of New York’s Limelight as an Aryan appropriation of Christian space for pagan dance rites, in “From Ultrasuede to Limelight: Halston & Gatien, Aryan Entrepreneurs in the Dark Age [89],” reprinted in my collection Green Nazis in Space! New Essays on Literature, Art, & Culture [90]; ed. Greg Johnson (San Francisco: Counter-Currents, 2015).

[20] [91] The article, “Freaky over Tiki,” gives a nice, condensed history of Tiki, congruent with the one given by our authors, but including Detroit’s legendary Chin Tiki [92] restaurant, which the authors here also ignore.

[21] [93] A while back, I was among a delegation of Counter-Currents folks who trekked down to Otto’s to take in alt-folk superstar David H. Williams, although the lovely Tesco Jane was not to be found.

[22] [94] Big Kahuna would no longer be welcome in Malibu [95]; big swinging dicks like Jackie Treehorn are, though, and you can hear Tiki icon Yma Sumac on the soundtrack during his elaborate beach party [96]. The confrontation of Lebowski and Treehorn brings together OT (Original Tiki) and Tiki Nouveau.

[23] [97] Parker was arguably right, since the only time Elvis was on his own abroad – military service in Germany – was when Elvis was introduced by Army doctors to the painkillers that would plague him for the rest of his short life.

[24] [98] Mad Men’s Don Draper will reverse the process, escaping Midwestern dreariness by joining the Army, then stealing another man’s identity in Korea, returning stateside to become a philandering (marital wandering) ad man with plenty of money and liquor, loving his work (“I want to work, damn it,” he insists when Bert Cooper suggests cashing out as he is doing) but “flowing from one” partnership to another.

[25] [99] “Annus Mirabilis” (where “me” was the poet Philip Larkin):

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me) –

Between the end of the “Chatterley” ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

Up to then there’d only been

A sort of bargaining,

A wrangle for the ring,

A shame that started at sixteen

And spread to everything.

Then all at once the quarrel sank:

Everyone felt the same,

And every life became

A brilliant breaking of the bank,

A quite unlosable game.

So life was never better than

In nineteen sixty-three

(Though just too late for me) –

Between the end of the “Chatterley” ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

[26] [100] The authors fail to note that this symbol, derived from TV, was as phony or inauthentic as anything Tiki produced. The current SmirkGate brouhaha shows how potent this symbol still is in the dominant media culture. Oddly, here the media is at pains to emphasize a (false) military background to the Indian; the real falsehood is denying that Native Americans have been warlike, right up to the present, where they join the military with pride. As a commenter at Unz notes [101], “Funny how the lunatic Left continually omits that portion of the Indian character from their vision of noble savages living in idyllic harmony with the land in some kind of pastoral North American utopia’ – a pretty good summary of the Woodstock ideal that replaced Tiki. Counter-Currents has frequently covered this; see, for example, “Lifestyles, Native and Imposed [102],” by Kevin Beary.

[27] [103] Beyond the authors’ scope is how Surf began to envelope other, white cultures, as this album review [104] observes: “With the space program beginning around this time, some of the surf-tunes began to take on intergalactic themes. In 1962, Telstar by England’s Tornados became a number one hit there and in the US! Out Of Limits by The Markett’s (revolving around a theme from Rod Serling’s sci fi TV show The Outer Limits [sic]) reached the number three spot on the pop charts in 1963. The surf sound also expanded to encompass phenomenon like drag car racing and skateboarding.” Space travel, drag racing and skateboarding are, of course, all implicitly white activities; for more on the last, see Buttercup Dew, here [105].

[28] [106] One can ask, could classical music be Tiki? Probably not, as it generally presents a kind of serious façade; since “classical” is a particular period, one of the attempts to refer to music by undead composers that isn’t pop is “serious music,” which suggests audience repellents like Schönberg. Kubrick’s music choices for 2001 play on this, contrasting the almost comical familiarity of “An der schönen, blauen Donau” with the eeriness of space. (Kubrick assumed all “classical” composers were dead, and was successfully sued [107] by the very alive, very “serious” composer György Ligeti for “distorting” his music.) However, so-called “early” music, especially of the dance sort [108], conveys both fun and strangeness (early, pre-baroque music, besides being old, is often for that reason also indistinguishable from Hindu or Arabic music, at least for the layman, a fact readily exploited by “multicultrural” fetishists [109]); also, the playfulness and exoticism of baroque opera, culminating in The Magic Flute, might serve in a pinch.

[29] [110] The Left always accuses its opponents of what it is doing.

[30] [111] See Joscelyn Godwin, Arktos: The Polar Myth in Science, Symbolism & Nazi Survival (Grand Rapids, Mi.: Phanes Press, 1996). Perhaps the most influential account is by Bal Gangadhar Tilak, The Arctic Home in the Vedas [112] (London: Arktos, 2011), who adduces William F. Warren [113] (the first President of Boston University), Paradise Found or the Cradle of the Human Race at the North Pole, as a predecessor.

[31] [114] The authors note that the same missionaries “found surfing to be disturbingly sensual, as the surfers were always nearly or completely naked.”

[32] [115] Partly nostalgia, and partly the idea that this hostile environment somehow “bred” the superior traits of Aryans; an oddly Boasian notion.

[33] [116] Similarly, Alex Kurtagic found role models for modern men in an exhibition of photos of broken-down nineteenth-century miners; see “Wild Boys vs. ‘Hard Men’ [117]” in The Homo & The Negro, op. cit. Lovecraft, a true Aryan, expressed horror at coldness, using this as a theme in a number of tales, most notably in “At the Mountains of Madness,” where he imagines what could be the shock of our Hyperborean ancestors if reawakened in today’s polar regions: “Poor devils! After all, they were not evil things of their kind. They were the men of another age and another order of being. Nature had played a hellish jest on them – as it will on any others that human madness, callousness, or cruelty may hereafter dig up in that hideously dead or sleeping polar waste – and this was their tragic homecoming. They had not been even savages – for what indeed had they done? That awful awakening in the cold of an unknown epoch . . . poor Old Ones! Scientists to the last – what had they done that we would not have done in their place? God, what intelligence and persistence! What a facing of the incredible, just as those carven kinsmen and forbears had faced things only a little less incredible! Radiates, vegetables, monstrosities, star spawn – whatever they had been, they were men!”

[34] [118] Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism and the Politics of Identity (N.Y.: New York University Press, 2002), p. 136.

[35] [119] Remember, Tiki is “about as far away from tuna casserole as the North Pole is from the South.”

[36] [120] Goodrick-Clarke, op. cit., p. 143. Mystical claptrap? “The Kaiser, intent on defying the Monroe Doctrine, had plans to set up a major naval Caribbean base in Cuba or Puerto Rico,” reveals [121] Gizmodo’s George Dvorsky. “From there, Germany could have access to South America, Central America, and the Panama Canal, which it planned on taking over once complete. Germany was clearly thinking big; it wanted nothing less than unhindered access to the Pacific Ocean.” Cited from “Caribbean Kaiser: The Super-Concerning Puerto Rican Public Relations Putsch of Rising Democratic Socialists of America Star Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez [122],” by Rainer Chlodwig von K.

[37] [123] And how is this different from similar manifestations in the guise of Hebrew mythology, or even the antiquated though European clerical dress of various Christian denominations?

[38] [124] See the essays collected in Magick for Housewives: Essays on Alt-Gurus [125] (Melbourne, Victoria: Manticore, 2018).

[39] [126] An anecdote from a woman whose parents would take her to visit Neville, relayed in a lecture by Mitch Horowitz.

[40] [127] For more details on Neville and his method, see Mitch Horowitz, The Miracle Club (Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions, 2018) and my review here [128].

[41] [129] Neville’s long out-of-touch brother, Victor, had decided to have the large, extended family together for the first time at Christmas, and, without any contact with Neville, sent him a first-class ticket and fifty dollars for a new suit. See The Miracle Club, Chapter Ten (Kindle loc. 2378).

[42] [130] Dan Steele adds elsewhere [131], “Said Abdullah to the unemployed, penniless (literally) Neville, ‘What?! Who said you are GOING to Barbados? A man of your stature? You are IN Barbados and you WENT 1st class!!!!’ Stature? Neville the penniless student? Neville, who couldn’t afford a $12 suit or a $3 pair of shoes? Besides bi-locating Neville practiced bi-stating. Abdullah had him imagine himself to be noble [arya!], a man of character, status, and prestige; a kind man, a man of charity and patience, a benevolent man who invested his power and knowledge in the uplifting of others. We are not here just to get good, but to give good.”

[43] [132] For an analysis – from the Left – of why Gabbard infuriates The Usual Suspects, see Caitlyn Johnstone, “Five Reasons I’m Excited About Tulsi Gabbard’s Candidacy [133].”