An Esoteric Commentary on the Volsung Saga, Part VII

Posted By Collin Cleary On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledPart I here [2], Part VIII here [3]

Chapter 8. The Vengeance of the Volsungs, Continued

In the last installment of this series, we learned of the life Sigmund leads in the forest with his son Sinfjotli – the product of Sigmund’s incestuous union with his sister, Signy. It is important to note, however, that at this point in the story, Sigmund has no idea that that union took place, or that Sinfjotli is his son. He thinks the boy is the child of Signy and the odious King Siggeir.

As part of his plan to seek revenge against Siggeir for the death of his father and brothers, Sigmund decides to put Sinfjotli through a process of training in the forest. This involves robbing and killing travelers. At one point, Sigmund introduces the boy to “the werewolf life” (as Kris Kershaw puts it). And so the two transform themselves into wolves and slaughter men together. I discussed at length the reasons why the story given in the saga is a garbled account of shapeshifting – and a rather hazy recollection of what was very probably a deliberate initiation rite.

At one point, Sigmund and Sinfjtoli quarrel while still in wolf form. Sigmund bites Sinfjotli in the neck and mortally wounds him. However, a raven appears bearing a magical leaf (yet another of Odin’s many appearances in the saga). When Sigmund puts the leaf on Sinfjotli’s wound, the boy springs up unharmed. I discussed the tradition of this magical leaf – or Lebenskraut (“leaf of life”) – as it survives in the tales of the Brothers Grimm.

In any case, after Sinfjotli is healed (much to Sigmund’s relief), they remain in wolf form until nine nights have passed. On the tenth day since putting on the wolf skins, father and son are finally able to remove them. The saga writer tells us that they curse the skins and then burn them, so that they will never harm anyone else. He tells us, further, that Sigmund and Sinfjotli did “many brave things” in the land of King Siggeir, during this “time of bad fate.”[1] [4] Nothing else is said about these exploits, and the saga writer then moves on to the account of Sigmund’s revenge against Siggeir.

However, some further information on the adventures of Sigmund and Sinfjotli is to be found in Beowulf. That poem predates the version of the Volsung exploits with which we are dealing here: the manuscript of Beowulf dates to 975-1025, whereas the Volsung Saga is dated to the late thirteenth century. Note, however, that these are only the manuscript dates: both texts relate to traditions that are much older. In Beowulf, Sigmund is “Sigemund,” his father Volsung is “Wæls,” and Sinfjotli is “Fitela.” At one point (lines 832-857), a minstrel relates some details about Sigemund. He refers to the “many feats and marvels,” the “struggles and wanderings of Wæls’s son.” An aura of mystery surrounds these in Beowulf also, as we are told that these are “things unknown to anyone, except Fitela.” Here, Fitela/Sinfjotli is described as the nephew of Sigemund, rather than his son. Of course, in Sigmund’s own eyes in the Volsung Saga – at least until the truth is revealed to him – he is the boy’s uncle.

The minstrel goes on to refer to “feuds” and “foul doings” to which Sigmund was party. Uncle and nephew are said to have killed giants: “their conquering swords had brought them down.” Sigemund’s fame and glory grew after his death, especially on account of “his courage when he killed the dragon.” We are told that “under gray stone he dared to enter [the dragon’s lair], all by himself to face the worst, without Fitela.” Sigemund drove his sword right through the dragon and into the rock wall of the dragon’s lair. “The hot dragon melted,” we are informed, possibly due to its boiling blood. Sigemund then makes off with the dragon’s vast hoard, loading it onto his boat. But this is all the minstrel has to say about Sigemund and Fitela.

In sum, Beowulf offers only two specific examples of the “further adventures” of Sigmund and Sinfjotli: killing giants, and killing a dragon and taking his treasure (which Sigemund accomplishes without Fitela). It is obvious, however, that the episode with the dragon is the same adventure that is related several chapters later in the Volsung Saga, where it is attributed to Sigurd, rather than Sigmund. (Even the small detail of “under gray stone” may refer to Sigemund crawling underneath the dragon to strike up at its belly – just as Sigurd does.) Thus, it appears that Beowulf transfers the dragon-slaying episode from Sigurd to Sigemund. Alternatively, there may have been different traditions, prior to Beowulf, that ascribed the dragon slaying to different figures, and it is just possible that in the earliest (oral) versions of the tale, the original dragon slayer may have been Sigemund/Sigmund.

To return to our story, once Sinfjotlu is fully grown, Sigmund decides it is time to carry out his revenge against Siggeir. They sneak into the King’s “house” and hide behind some beer barrels outside the main hall. Somehow, Sigmund has warned Signy of their arrival, and she comes to meet them. The three agree on a plan, and it is decided that they will carry it out when night falls. The saga writer then tells us that Signy’s two young boys are playing with some gold pieces nearby, rolling them on the floor. (These must be children she has had with Siggeir since the first two were slaughtered by Sigmund, and since the birth of Sinfjotli.)

One of the gold pieces gets away from the children and rolls behind the beer barrels. When one of the boys goes to retrieve it, he finds Sigmund and Sinfjotli hiding. Immediately, he rushes into the hall to inform his father, who correctly infers that some treachery is afoot. Signy witnesses this. She takes both boys by the hand and leads them out of the hall and to Sigmund. “I advise you to kill them,” she says. And one suspects, given earlier events, that Sigmund will gladly oblige her. Yet he refuses. “I will not kill your children, even if they’ve betrayed me,”[2] [5] he says. Why does Sigmund refuse to kill the boys?

Had Sigmund not killed the other two children – the ones who failed the test with the serpent – they could have revealed his presence to King Siggeir. Furthermore, killing Siggeir’s descendants has to be part of Sigmund’s plan for revenge: if any of Siggeir’s children were left alive, they would seek revenge against Sigmund. This is, of course, the reason why Siggeir himself sought to kill all the Volsungs, save Signy. It therefore makes sense that Sigmund should be willing to kill the two younger sons of Siggeir, who have just betrayed him. But his words to Signy strongly suggest that he is weary of killing children. Sinfjotli, however, has no such qualms: “he drew his sword and killed both children, and threw them into the hall at the feet of King Siggeir.”[3] [6]

Siggeir orders his men to seize Sigmund and Sinfjotli. The valiant pair put up a good fight, but they are quickly overwhelmed, captured, and put in chains. The sadistic King Siggeir then enjoys contemplating what sort of execution would be the slowest and most unpleasant. He finally decides to entomb them in a burial mound and let the pair either slowly suffocate or starve to death. (Since the mound is described as being made of stone and turf, it is likely that there would be ventilation through tiny cracks in the materials – so starvation seems the more likely outcome.) Siggeir orders that the two men be separated by a very large, flat stone set upright, dividing the interior of the mound into two chambers, “because he thought it would be worse for them to be separated even though they could hear one another.”[4] [7] It is important to note that at this point in the story it is not clear that Siggeir is aware of the identity of Sigmund and Sinfjotli, and that they are Volsungs (the text will soon give us reason to think that he only comes to learn this later).

Slaves are ordered to seal the mound. As they are doing so, Signy appears and tosses a bundle of straw into Sinfjotli’s side of the mound. She orders the slaves not to tell Siggeir that she has done this. Later, at nightfall, Sinfjotli calls to Sigmund: “I don’t expect we’ll lack food for a while. Queen Signy has thrown a side of bacon into the mound for us, and wrapped it up in straw.”[5] [8] Of course, this is a goof on the part of the saga writer. If Sigmund and Sinfjotli are kept apart by the great stone mentioned earlier (and described in detail in the chapter), how can they possibly share food with each other? And why does Sinfjotli simply assume that he’s been tossed a side of bacon? (Perhaps in an earlier version of the story, Signy mentions this when she tosses in the bundle of straw.)

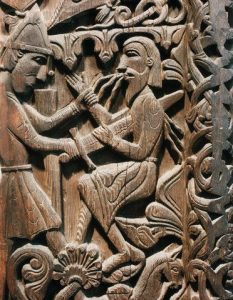

Sinfjotli quickly discovers, however, that it is not a side of bacon the straw conceals but Sigmund’s sword – the one he received as a gift from Odin, having pulled it from the tree Barnstokk. Sigmund and Sinfjotli are jubilant, for they know that with this mighty sword they can free themselves from the tomb. The description of how they go about doing so is, however, a bit confusing:

Now Sinfjotli stabbed up through the earth above the stone and cut hard. The sword bit into the stone. Then Sigmund took the point of the blade in hand and the two of them together sawed through the stone until it was split in half . . . And now they were both free to move around in the burial mound, and they cut through stone and iron [their chains?] and escaped.[6] [9]

What seems to be meant is that Sinfjotli plunges the sword into the layer of earth above the stone, resting against its top end. He shoves the tip of the sword toward Sigmund’s side and begins cutting. Sigmund takes the tip of the sword in hand and, the two of them using the sword together like a saw, they cut the stone in two. In his description, the saga writer quotes a poetic source, introducing it with “as the poem tells”:

They cut that great stone

with their strength.

Sigmund wielded the sword,

and Sinfjotli did as well.

These lines actually come from a poem now lost to us (they do not appear in the Poetic Edda). They represent a brief, tantalizing glimpse of the lost sources on which the saga writer based his text.

Sigmund and Sinfjotli now set fire to Siggeir’s hall, whose occupants awaken to find the building blazing around them. Siggeir calls out from the hall, asking who has done this. Sigmund replies, “Here I am with Sinfjotli, my nephew, and now we think that you ought to know that not all the Volsungs are dead.” Sigmund then asks for Signy to come outside so that he can honor her. “He said that he wanted to compensate her this way for her miseries.”[7] [10]

Signy emerges – and proceeds to reveal everything to Sigmund:

Now you will see whether I have remembered the murder of King Volsung by King Siggeir. I had our children killed, when I thought they were too slow to avenge our father, and Sigmund, I went to you in the forest disguised as a sorceress, and Sinfjotli is your and my son. He is exceedingly manly, because he is the son of both a son and a daughter of Volsung.[8] [11]

The description of Sinfjotli as “exceedingly manly” continues the practice, of which there are several examples in the saga, of emphasizing the size, strength, and virility of the male members of the Volsung clan. As noted in a previous installment of this essay, each generation of Volsungs seems to be bigger, stronger, braver, and more virile than the last. (Though it is not clear that Sinfjotli is more powerful than Sigmund, indeed there is reason to think he is not: Chapter Seven informs us that, unlike Sigmund, Sinfjotli could not eat or drink poison, though he could survive poison falling on his skin.) The most extreme praise is reserved for Sigurd, greatest of the Volsung clan, and, as we will see, the description of his manly virtues occupies an entire chapter.

Signy goes on to say that all she has done has been to bring about the death of Siggeir. But she adds, “I have done so much to accomplish my vengeance that I cannot choose to live.”[9] [12] She has, of course, done terrible things to realize the vengeance of the Volsungs against Siggeir: including committing incest with her own brother, and (as she mentions) having her children killed. I have noted in previous installments that one major theme of the saga is that the Volsungs seem to always find themselves committing great crimes. And one wonders if this is all part of Odin’s plan. Is it necessary for them to transgress human laws and mores, and to commit acts of almost unimaginable cruelty and callousness, in order for them to become the race of super-warriors Odin wishes to breed (all of whom, upon death, shall be recruited into his army of the Einherjar)? It is interesting, however, that so far in the saga, the most heinous deeds of all have been committed by a Volsung woman.

In any case, Signy announces that she intends now to die with Siggeir – by choice (even though she had had no choice about living with him). After kissing both Sigmund and Sinfjotli goodbye, she returns to the blazing hall and dies there with Siggeir and all his men. We will see the character of Signy reborn in Gudrun, the wife of Sigurd: the story of Gudrun (or “Kriemhild” in the Nibelugenlied) and her revenge against her husband’s murderers repeats a number of motifs from the life of Signy, including killing her own children and burning down her hated husband’s hall.

We are told that after the death of Signy, Sigmund and Sinfjotli “got an army and ships.” We are not told how they accomplish this, but we have already seen that such things seem to simply fall into place for the Volsungs (one suspects, of course, the hand of Odin at work). Sigmund and son return to the ancestral lands of the Volsungs. Many years, of course, have passed since the entire clan left there on their ill-fated visit to King Siggeir. In the meantime, a pretender has claimed the Volsung kingdom. But Sigmund and Sinfjotli drive him out, and Sigmund becomes a great and powerful king, “both wise and well-advised.”[10] [13] And he decides to remarry. However, Sigmund makes a bad choice. As we will see in chapters to come that his new wife, Borghild, turns out to be a witch, who harbors nothing but malice toward Sinfjotli.

Sigmund and Borghild have two sons together, Helgi and Hamund. The saga writer tells us that when Helgi was born, the norns visited him “to determine his fate.” We should not assume, however, that this refers to the “three weird sisters” with whom most readers are familiar: Urth, Verdandi, and Skuld. After discussing those three in his Prose Edda, Snorri states that “[t]here are other norns who visit everyone when they are born to shape their lives, and these are of divine origin, though others are of the race of elves, and a third group are of the race of dwarfs.”[11] [14] Thus, there is actually an indefinite number of norns. Those who visit Helgi declare that he is destined to become “the most famous of all kings.”

At just about the same time, Sigmund returns from battle, and the saga writer gives us some insight into Norse naming customs. Sigmund gives his son a clove of garlic (it is not clear what the significance of this is) and the name “Helgi.” As a “naming gift,” he also gives him the lands of Hringstathir and Solfjoll, as well as a sword. He also urges the infant to “do great things and to be a Volsung.”[12] [15]

And Helgi does turn out to be quite a Volsung, indeed. We are told that not only was he “better than other men at every kind of skill,” he rode into battle at the tender age of fifteen![13] [16] Sigmund makes Helgi king over the army, and together with Sinfjotli, they command the troops. It should not puzzle us why Sigmund gives the leadership position to Helgi, rather than Sinfjotli. Helgi is, after all, the product of his marriage to his Queen, Borghild, while Sinfjotli, even though he is older, is an illegitimate child. (Furthermore, the “official story” Sigmund may have adopted with Borghild and others is that Sinfjotli is his nephew.) To have favored Sinfjotli over Helgi would have insulted Borghild. And, as will soon become apparent, she does not need any more reasons to resent Sinfjotli.

The story of Helgi is told in the next chapter of the saga. It constitutes a digression from the main story, though a very interesting and illuminating one.

Notes

[1] [17] The Saga of the Volsungs with the Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok, trans. Jackson Crawford (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2017), 12.

[2] [18] Crawford, 12.

[3] [19] Crawford, 12.

[4] [20] Crawford, 13.

[5] [21] Crawford, 13.

[6] [22] Crawford, 13.

[7] [23] Crawford, 13.

[8] [24] Crawford, 14.

[9] [25] Crawford, 14.

[10] [26] Crawford, 14.

[11] [27] Snorri Sturluson, Edda, trans. Anthony Faulkes (London: Everyman’s Library, 1995), 18.

[12] [28] Crawford, 14.

[13] [29] Crawford, 14.