Now in Audio Version!

Ten Great Films Against the Modern World, Part I

Posted By

John Morgan

On

In

Counter-Currents Radio,North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

Part 1 of 2 (Part 2 here [2])

To listen in a player, click here [3]. To download the mp3, right-click here [4] and choose “save link as” or “save target as.” To subscribe to the CC podcast RSS feed, click here [5].

Some friends recently asked me to draw up a list of a few films that have made a lasting impression on me, aesthetically, emotionally, intellectually, or however, over the course of my life thus far. When I realized how many films I would have to include in order for it to be complete, it grew to be quite long – ninety-four so far, and I plan to stop at one hundred. Greg Johnson asked me to write up a few of them, so I selected ten from my list that I think are particularly relevant for anti-modernists or people on the Right more generally. I might eventually write about some of these in greater depth, but here is just enough, hopefully, to whet the reader’s interest.

Cinema is among the newest art forms, and has only been made possible by the technology of the modern, industrialized world; nevertheless, I believe that a great film is every bit as worthy a part of our civilization as a great book, piece of music, or work of art, and can be used to undermine the modern world. Certainly, some of the films I’ve loved over the years are part of what motivated me to be in “revolt against the modern world” and shaped me in that regard. I believe that the ones I have selected here amply demonstrate this. Not all of the films I have listed are necessarily against the modern world per se; it might be more accurate for some of them to say that they depict characters alienated from the modern world, or which question aspects of modernity. Apart from the first two, they are in no particular order.

1. Andrei Tarkovsky, Stalker (1979)

I recently did a Guide to Kulchur podcast on this film [7] with Fróði Midjord. For me, Tarkovsky is the consummate filmmaker; as many other directors have acknowledged, he was a poet of the cinema who made presenting the subconscious on screen seem easy. All of Tarkovsky’s mature films are masterpieces, but for me Stalker stands out as his fullest statement on what it means to be human in the modern, Western world. The story is quite simple. The film is set in an unspecified time and place, but which greatly resembles the late Soviet Union it was made in; the characters live in an industrial wasteland. Some years before the film takes place, extraterrestrials briefly landed in the area and left behind a place called the Zone: a mysterious realm in which the ruins of the town which once stood there have been transformed into an ever-changing and moving series of lethal traps, at the center of which there is said to be a room which grants the wishes of whoever enters it. Although the state has made entry into the Zone illegal, there are some who nevertheless enter it anyway and who can intuitively detect – at least sometimes – where the traps are located, and thus can guide others to this room; they are known as Stalkers. Two men known only as Writer and Professor hire a Stalker to take them to this room, and the film is the story of their journey in both its inner and outer dimensions.

For me, the four main characters represent the various aspects of a human mind: Professor represents the rational and scientific element, Writer is the artistic and creative part, Stalker is the religious and faith-driven part, and the Stalker’s wife, who has only a minor yet crucial role, is the feminine aspect. Their attempt to grapple with the Zone forces them to question their beliefs and confront their innermost natures; the resulting dialogue and interactions between them suggest a modern mind at war with itself and the surrounding world, striving to attain balance between its various components in a reality that is itself insanely out of balance. Their quest to reach the room could be seen as a religious or as a psychological allegory, depending on how one wants to read it, but viewing it never fails to shake me to my core. Anyone who has meditated on the meaning of an individual life trying to make its way in the barren harshness of the modern world, continually buffeted by forces we can often only dimly understand, will surely find much poetry and food for thought in this tale.

2. Stanley Kubrick, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

2001 was my favorite film when I was young until I discovered Tarkovsky. I date the origins of my own coming into a mature consciousness from my childhood viewings of it. 2001 is the ultimate expression of the Western Faustian spirit on film (Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, while a great film in its own right, was a pale imitation and rehash of many of 2001’s themes), made by the greatest perfectionist the world of cinema has yet seen. It is divided into four parts: the first showing the dawn of human consciousness in African apes four million years ago, the second depicting the discovery of a mysterious object left behind by extraterrestrials by astronauts on the Moon, the third being about a voyage to Jupiter and a struggle between the human astronauts aboard and the ship’s superintelligent computer, and the fourth being a journey “beyond the infinite,” as the film itself tells us.

2001 is perhaps the boldest and furthest-reaching film ever made, and is both a paean to the possibilities of evolution and technology as well as a warning about their possible limitations – and without a single hint of political correctness. Yes, perhaps one day man will be able to conquer the stars, but will he lose those qualities which make him uniquely human in the process? Will our technology advance to the point where we lose the ability to differentiate between our tools and ourselves, especially as represented by the twin dilemmas of the problem of dehumanization and the possibilities of artificial intelligence? (2001 was the first film to examine the latter question in depth.) But more than this, 2001 conveys to the viewer the immensity of time and space, and the tininess of our own place in them, more completely than any other visual effort I’ve seen. And the last quarter of the film remains one of the most mind-blowing sequences ever recorded, where the infinite reaches of the universe and the esoteric combine into a vision of man’s destiny and purpose which viewers will be debating the meaning of for as long as cinema survives. For those who believe in the ongoing potential of Western civilization, it is inspiring. The film’s special effects and its vision of future space technology have also aged remarkably well.

3. Donald Cammell & Nicolas Roeg, Performance (1970)

Performance is a forgotten piece of late 1960s cinema (it came out in 1970, but was actually filmed in 1968, when the studio was so horrified by its violence and sex that they refused to release it for two years) that attempted to cash in on the hippie subculture, and on the surface it might seem like no more than that. But in fact the film has a great deal more depth, being, rather like the films above, more of an exploration of the condition of the individual in modern, Western society. When the film is remembered at all, it is usually for the fact that it stars Mick Jagger in his prime, but it managed to wisely sidestep the usual pitfalls and shallowness of cinematic pop star vehicles.

The story is about an East London gangster named Chas (James Fox) who gets into a conflict with a rival gangster and childhood friend, and ends up killing him in a fit of anger after he is attacked. Being hunted both by the police and his own colleagues, who want to quietly dispose of him before the police can track him down and thus jeopardize their own position, he ends up taking refuge under a false identity in a run-down manor house in Notting Hill owned by a washed-up rock star named Turner (played by Jagger), who is vainly hoping to restore his lost inspiration. Turner shares the house with his two lovers, played by Anita Pallenberg (who was dating Brian Jones at the time) and Michèle Breton. Chas and his new housemates loathe each other at first, but things take an interesting turn when Turner and his girlfriends decide to administer a heroic dose of psychedelic mushrooms to him without his knowledge.

This scenario may sound trite, and perhaps silly, at first, but in the film it is given multiple allegorical and symbolic levels, and visually it is shot in an extremely unconventional, disorienting, and yes, psychedelic style – certainly being one of the better attempts to portray the psychedelic experience on film. The elements of the plot are thus amplified to encompass much grander themes dealing with the very nature of man, history, society, and our historical moment. As indicated by various cues in the visuals and dialogue throughout the film, Chas’ gang is symbolic of the masculine forces of order, patriarchy, tradition, conformity, progress (in the purely technical and organizational sense), aggression, domination, sexual repression, and violence (“a bit old fashioned,” as Chas says); Turner and his girlfriends represent the feminine forces of creativity, individualism, spirituality, open sexuality, fluidity, ambiguity, change, and chaos. There are many possible readings, but for me (and others) the message of the film seems to be that both of these elements are incomplete on their own; in order to achieve wholeness, especially in a world ruled by violence of every sort, the two must achieve a synthesis. There is a great deal of esoteric symbolism in it as well. For those who feel simultaneously drawn to the worlds of tradition and to the “dark side,” you may find in Performance a fascinating exploration of the consequences that might result from bringing them together.

4. Sam Peckinpah, Cross of Iron (1977)

I’ve always had a fondness for war films, but Cross of Iron remains my favorite film about the Second World War – not because it is the most grandiose or historically accurate, but because for me it remains the most compelling and unconventional one. It is also one of a very few films of which I’m aware which focuses on the German experience on the Eastern Front. The story is about a German stay-behind platoon in the Crimean wilderness in the summer of 1943, which is tasked with following behind the retreating Wehrmacht and wreaking havoc using guerrilla-style attacks on the Red Army. The platoon is commanded by Sergeant Steiner (James Coburn), who comes into conflict with his new commanding officer, Captain von Stransky (Maximilian Schell), a cowardly Prussian aristocrat who makes it clear that he is only interested in remaining on the Eastern Front long enough to win an Iron Cross for himself and then go back to France. When von Stransky lies about his heroism in a battle in an attempt to expedite the process, Steiner, enraged by his duplicity, threatens to expose him. Von Stransky then manipulates his men into “accidentally” leaving Steiner’s platoon behind during a Soviet assault, thinking that Steiner will be killed or captured and thus removing his only obstacle to the Iron Cross. Steiner, however, manages to survive, and leads his men in a desperate attempt to cross through Russian-held territory and rejoin the Wehrmacht.

Unlike the others I’ve been discussing, Cross of Iron doesn’t have a lot of symbolic depth, but in addition to being a riveting depiction of action on the Eastern Front (it has some of the most intense battle scenes anywhere), it features a number of wonderful performances (James Mason also plays a German officer). The conflict between Steiner, as a simple soldier trying to keep himself and his men alive, and von Stransky, who exploits his noble position for his own selfish ends, is also quite fascinating. Steiner represents a more traditional hero; uninterested in bravado, his machismo is exhibited in his willingness to assume responsibility for his men’s lives at all costs, and in his efforts to retain a shred of human dignity in the midst of the slaughterhouse of total war. Von Stransky, in contrast, is the little man of modernity, clinging to his titles, his deceptions, and his scheming, and projecting false bravado to cover up the fact that he is actually a poor excuse for a man, let alone an aristocrat. It is also filmed in an unconventional style, with quick cuts intended to convey the chaos of battle, and sometimes crossing over into the hallucinatory. The violence is still quite graphic, even by today’s standards. But if you’re in the mood for a gritty, dark war film, you will surely value Cross of Iron.

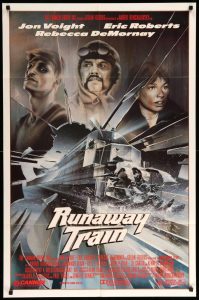

5. Andrei Konchalovsky, Runaway Train (1985)

[12]Konchalovsky collaborated with Tarkovsky on some of his early films, and the first draft of Runaway Train’s script was written by the famous Japanese auteur Akira Kurosawa, but you wouldn’t know it from the film itself, which is the opposite of Tarkovsky’s and Kurosawa’s aesthetics in nearly every respect. It’s a prison break film, in which a convicted bank robber, Oscar “Manny” Manheim (Jon Voight), is serving a sentence in a maximum-security prison in Alaska run by Warden Ranken (John P. Ryan). Manny and Ranken despise each other in a visceral way, and after Ranken is forced to release Manny from permanent solitary confinement due to a court order, Manny realizes that he has to find a way to escape before Ranken can have him killed. He eventually does escape with another prisoner, Buck McGeehy (Eric Roberts), and they make their way across the Alaskan wilderness until they finally come across a trainyard, and hop aboard a departing freight train, which they believe will take them out of Alaska and to freedom. Unbeknownst to them, however, the train’s sole engineer has a fatal heart attack while leaving the yard, and the train is then stuck barreling down the tracks with ever-increasing speed with no one able to stop it. Meanwhile, Ranken has discovered where they are and tries to hunt them down before they can escape.

[12]Konchalovsky collaborated with Tarkovsky on some of his early films, and the first draft of Runaway Train’s script was written by the famous Japanese auteur Akira Kurosawa, but you wouldn’t know it from the film itself, which is the opposite of Tarkovsky’s and Kurosawa’s aesthetics in nearly every respect. It’s a prison break film, in which a convicted bank robber, Oscar “Manny” Manheim (Jon Voight), is serving a sentence in a maximum-security prison in Alaska run by Warden Ranken (John P. Ryan). Manny and Ranken despise each other in a visceral way, and after Ranken is forced to release Manny from permanent solitary confinement due to a court order, Manny realizes that he has to find a way to escape before Ranken can have him killed. He eventually does escape with another prisoner, Buck McGeehy (Eric Roberts), and they make their way across the Alaskan wilderness until they finally come across a trainyard, and hop aboard a departing freight train, which they believe will take them out of Alaska and to freedom. Unbeknownst to them, however, the train’s sole engineer has a fatal heart attack while leaving the yard, and the train is then stuck barreling down the tracks with ever-increasing speed with no one able to stop it. Meanwhile, Ranken has discovered where they are and tries to hunt them down before they can escape.

Runaway Train is one of the most ultra-masculine films ever made. Manny is a primal, animalistic force, completely amoral and uninterested in anything apart from achieving his own freedom. Ranken, we come to see, is really the same as Manny, and is just as animalistic; the only difference between them is that the bourgeois world has conferred authority on Ranken to protect them from people like Manny. The world outside the prison, as represented by the railway supervisors frantically trying to find a way to stop the train before it collides with something, is shown to be weak, impotent, and effeminate. The film is also implicitly anti-feminist; the only female characters in the film are depicted as being completely worthless towards doing anything about the situation. The film also has some of the greatest, if troubling, dialogue ever written in its critique of modern social life. Manny is a hero, but only of an existential nature; he doesn’t fight for any cause other than himself, but his struggle can be seen as that of all of us who refuse to accept that life in the modern world has to consist purely of conformity and submission. When you need a high-testosterone evening’s entertainment while remaining physically inactive, Runaway Train is a good choice.