The Republican Workers Party:

A Review

Posted By

Spencer J. Quinn

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

F. H. Buckley

The Republican Workers Party: How the Trump Victory Drove Everyone Crazy, and Why It Was Just What We Needed

New York: Encounter Books, 2018

Any book that celebrates the 2016 election while denying the crucial role that race and ethnonationalism played in the rise of Donald Trump is just asking not to be taken seriously. Such a book would have more to offer than petty insults from a NeverTrumper or vindictive hate from a liberal Democrat. Such a book would also, however, completely miss the historical trends which are currently sweeping not just the United States, but the entire Western world. The Republican Workers Party by F. H. Buckley is one such book.

An attorney and Professor of Law, Buckley (no relation to National Review’s William F.) is a senior editor at The American Spectator who, along with his wife Esther Goldberg, wrote speeches for candidate Trump. As an author, he’s highly thoughtful, and has an irrepressible interest in both government and history, which shows in every chapter of The Republican Workers Party.

To distill Buckley down to epithets, he’s both a Marxist who understands economics and a civic nationalist true-believer. For the Dissident Right, that’s strikes one and two right there. Sure, he means well and seems genuine. In The Republican Workers Party he takes admirable pains to keep his ideas consistent. I want to give him an A for effort. I also want to give him an F for almost everything else. But Buckley does a little better than that. There’s some good stuff in The Republican Workers Party, despite the book’s scrupulous, almost precious, circumvention of everything tribal in human nature.

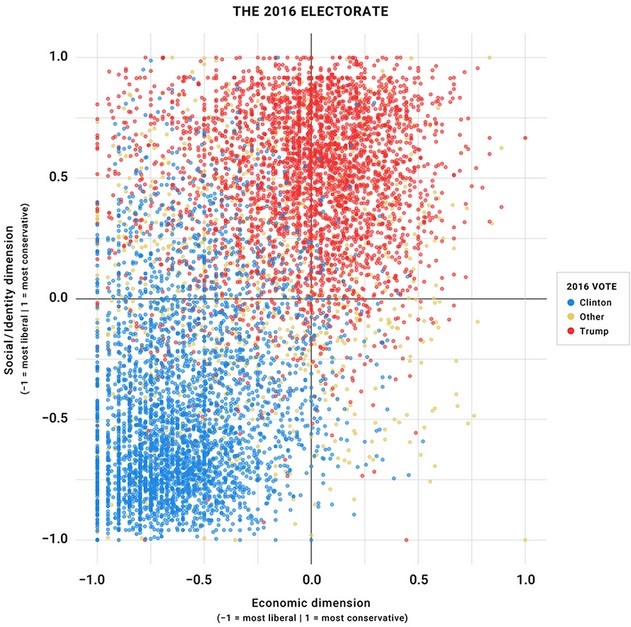

Buckley describes his Republican Workers Party (hereafter, RWP) in a chapter entitled “The Two-Dimensional Man.” The two-dimensional man, of course, is Trump, who was the first Republican in a long time to view the Left-Right divide in more than just economic terms. Before Trump, according to Buckley, the Republican leadership painted themselves mostly as conservative, free-market avengers attempting to slay the socialist, Democratic dragon. But this perspective is far too limited. Taking inspiration from Frankfurt School figure Herbert Marcuse, who pried the Left away from its economic obsessions in the 1960s, Buckley states that there are really two axes splitting Right and Left: an economic one and a non-economic (or social) one. For a neat visualization, Buckley provides the graph below [3], which was developed by Lee Drutman of the Voter Survey Group in June 2017:

Here is what Buckley has to say about it (emphasis mine), and read carefully, because this is as good as political science gets:

The diagram divided voters into four quadrants. The 44.6 percent who fell into the lower-left quadrant were strongly left-wing on both economic and social issues. Some of them voted for the Green Party candidate, Jill Stein, while some even voted for Trump, but more than four-fifths voted for Hillary Clinton. Next, the antipodean upper-right quadrant was composed of conservatives who were both socially and economically right-wing. They constituted 22.7 percent of all voters, and nine-tenths of them voted for Trump. A miniscule 3.8 percent of the voters were libertarians in the lower-right quadrant, socially left-wing and economically right-wing, and they split their votes evenly between Trump and Clinton. Finally, 28.9 percent of the voters occupied the upper-left quadrant, economically left-wing but socially right-wing. Drutman called them “populists,” but I prefer the label that Trump himself gave them: the Republican Workers Party. They went three to one for Trump.

So the upper-left quadrant made all the difference in 2016. By running on “America first” protectionism and promising to be a “jobs president” in ways that violated the tenets of free-market capitalism and neocon globalism (two core strands of GOP thinking at that time), Trump actually took voters in the upper-left quadrant away from the Democrats. By treating an abstract idea as if it were concrete, Trump in effect Moneyballed his way to the White House; unlike in Moneyball, however, he did it before the numbers were crunched, not after.

The remainder of the book rambles more or less coherently on what it means to be part of the Republican Workers Party (RWP). All the while, Buckley ties himself into knots to avoid an honest discussion of the elephant in the room: race. He informs us that Trump and the RWP are nationalist, not populist. The term “populist,” of course, is tainted with America’s original sin of racism. Buckley offers the South Carolina politician and ardent segregationist “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman (who served from 1890 until the First World War) as what he considers to be a particularly odious example of populism. Buckley can’t have his blond-haired paladin be likened to that. (Never mind, of course, the corruption, violence, and crime that the black population inflicted upon the disenfranchised whites during Reconstruction, which caused them to want segregation to begin with).

Buckley insists that Western (and American) culture has no room for White Nationalism because both have always absorbed “foreign elements” and became better for it. His examples are either laughably weak (Rome appropriating Greek philosophy) or laughably trivial (Langston Hughes, Amy Tan, and Norah Jones as paragons of racial diversity). This is ridiculous since there is no reason why a white ethnostate couldn’t borrow aspects of other cultures and still remain white. He also calls for US immigration to more closely resemble Canada’s, and be based on merit. He then (ludicrously) dodges any charge of racism by claiming that “Canada will admit highly skilled Nigerians while excluding low-skilled ones. Hard to see much racism there.”

Yes, unless someone asks you why Canada takes in so few highly-skilled Nigerians proportionate to, say, highly-skilled Chinese. To admit that China simply produces more highly-skilled people per capita than Nigeria does would be considered racist. But Buckley ignores this contingency. How could this possibly be persuasive to the thoughtful reader?

Empathy as a theme appears often in this work, and this makes sense, given Buckley’s admittedly Marxist and Christian sympathies. He wants to see a mobile, classless society in which the poor are provided for. One can take or leave that, but, to his main point, Buckley strives to prove that of all the candidates in 2016, Trump had the most empathy for the most people. In a chapter enumerating how the Cruz-Romney wing of the GOP lacked empathy for the poor, Buckley touches upon the seemingly aristocratic idea of “blaming the victim.” In other words, why have too much concern for the poor when poor people are typically too stupid or lazy to not be poor? He dings Mitt Romney especially hard over this for his “forty-seven percent” gaffe from 2012. But as for any truth behind the claim and the racial stink it invariably raises, Buckley has this to say:

There were two problems with the moral poverty theories, however. First, they predicted that things could only get worse, that with the rise of unwed births the inner cities would become abandoned to gangs of feral youths, but this didn’t happen. Instead, crime rates went down, as youthful offenders confronted economic realities in the form of stiffer criminal penalties. Second, none of this explained the difference in the black and white rates of crime and unwed birth, unless one wanted to wade into the swamp of black-white differences. Apart from out-and-out racists, no one wanted to go there, but both conservatives and liberals were content to let the question linger.

This paragraph is an astounding example of writing something without saying anything. In order to refute the “blame the victim” mentality (if we can even call it that), Buckley first knocks down a straw man, i.e., the idea that “blaming the victim” entails predicting that “things could only get worse.” Buckley’s assertion that things have gotten better in the inner cities 1. does not disprove racial differences in intelligence or temperament; 2. is incorrect, since things have gotten worse during this decade, according to Edwin Rubinstein’s 2016 edition of The Color of Crime [5]; 3. dishonestly fails to mention that while inner city crime rates did go down in the mid-1990s, they were still quite bad; and 4. offers no source for his opinions. The Republican Workers Party has over two hundred footnotes; you’d think Buckley would have included one for this humdinger – but no.

Secondly, Buckley reasons that because only “out-and-out racists” would bother investigating racial differences, the question of whether blaming the victim has any merit remains forever moot. Could you possibly have a more cowardly argument than this? Doesn’t his reasoning also beg the question when it assumes that one would have to be an “out-and-out racist” (whatever that is) before studying racial differences? Couldn’t one become a race realist only after studying the data?

Buckley then tries to dispel racial attitudes towards poverty by pointing out how white illegitimacy rates have increased at the same time that black ones have. But he lies by omission. He doesn’t mention that white illegitimacy still happens far less frequently than black illegitimacy. He also doesn’t compare the vastly dissimilar crime and academic achievement rates between poor whites and blacks. Such stark differences are what the social sciences are made for. Yet Buckley ignores them.

Here’s a great example of how tone-deaf Buckley is about the rise of Trump. He believes that people voted for Trump because they were worried most of all about “intergenerational immobility.” Talk about theoretical nonsense! This term is so obscure that he has to define it himself. And if he has to actually define it, then what makes him think that voters had it on the tips of their tongues in 2016, when they put Trump over the top? According to Buckley, the following list of concerns were less important to Trump supporters than whether their grandkids would one day be as wealthy as they are:

- Concern about how whites are losing their nation to hostile and unassimilable foreigners

- Concern about how whites are feeling like second-class citizens in a nation that is increasingly anti-white

- Concern about how the West is becoming overrun by Islam and jihadist attacks

- Concern about endless foreign wars being waged for dubious purposes

- Concern about how the first black president in American history presided over record levels of economic stagnation and unemployment

Buckley seems to think that because a few studies point to intergenerational immobility, and because Richard Dawkins wrote a book called The Selfish Gene, people ran to the polls to vote for Trump. This is tantamount to claiming that the chant “Build the wall!” is really about reducing our $22 trillion debt.

What’s worse, Buckley refuses to give the racial argument a fair hearing. He effectively sweeps the Alt Right under the rug, barely giving it a mention. He claims to have avoided such people when looking for folks to work with on the Trump campaign (they have cooties, don’t you know). He also resorts to insults a few times, referring to the Unite the Right people in Charlottesville in August 2017 as “moral lepers,” and Alt Right people in general as “monsters” (this, coming from the person who tut-tuts Hillary Clinton for referring to half of Trump’s base as “deplorables”).

Clearly, the topic of race gives Buckley the willies. While this gets pretty annoying, I will say this: by mentioning the Alt Right so infrequently in his book, he bashes it infrequently as well – which is perversely refreshing, if you think about it. He also does a decent job of turning the tables against the Left. For example, instead of cucking out and lamenting the Nazi paraphernalia of some of the Charlottesville marchers, he punches back, likening the paranoid Nazi-hunting media to the paranoid Commie-hunting John Birch Society from sixty years ago. Not bad, right? Further, one of the good things about being a genuine civic nationalist is that when he goes to bat for white people, he means it. Unlike the sneering elitist Kevin Williamson of National Review, who once claimed that Donald Trump speeches were like OxyContin for poor whites, F. H. Buckley expresses real humanitarian concern for the high rates of suicide and drug addiction among white people. He does his best to stay true to this empathy thing, and deserves credit for that.

This might be the best he has say to say about it:

The Marxist dream of universal brotherhood and a class-free world has died, in the moral and political bankruptcy of communism. Among the progressive Left it has been abandoned for identity politics that explicitly deny a common humanity by granting priority to favored groups – minorities, gays, women. Yesterday’s kulaks are today’s white men.

Of course, we all know that not everything is about race. Whenever Buckley is not forced to write about it, The Republican Workers Party improves dramatically. His treatment of Michael Anton’s groundbreaking essay “The Flight 93 Election [6]” is enlightening. He shares a few memorable anecdotes. And his chapter on draining the swamp is nothing short of brilliant. Buckley understands the dangers of government regulation, and when he holds forth on it, the reader is treated to one clear passage after another. Granted, it’s a specialized topic which won’t appeal to many. On the other hand, somebody has to write about it.

The Republican Workers Party is by no means a great book. Its obvious flaws aside, it’s also quite undisciplined. Many passages ramble without clear direction. The book is only 156 pages long, yet I can honestly call it long-winded. Furthermore, it’s insufferably pretentious. Buckley feels the need to buttress nearly every point he makes with some classical allusion or untranslated foreign phrase, or an apropos movie quote or reference to a famous novel. At one point, not only does he go to Shakespeare to help describe the arrogance of Trump’s critics, he follows it up with a 213-word exegesis on Albert Camus’ The Stranger. Was this really necessary? What purpose does this serve other than to show off the author’s (or his research assistant’s) extensive erudition?

F. H. Buckley’s reasons for tripping gleefully on Donald Trump’s success are frankly wrong and will ultimately be forgotten as civic nationalism becomes less and less workable in a multiracial West. In this sense, he reminds me of one of the many forgotten Menshevik theorists who triumphantly ran around St. Petersburg in March 1917. They were taking credit for what was happening, but what was going to happen, they never saw coming.

Spencer J. Quinn is a frequent contributor to Counter-Currents and the author of the novel White Like You [7].