David Lynch’s Dune

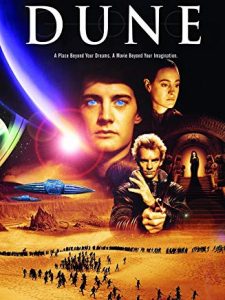

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledDavid Lynch’s third feature film is his 1984 adaptation of Frank Herbert’s science fiction classic Dune. Herbert’s Dune is widely hailed as a masterpiece, while Lynch’s Dune has a much more mixed reputation, tending toward the negative. When I first saw Lynch’s Dune, I was deeply disappointed. Herbert’s novel had left a powerful and vivid impression on me, and Lynch’s vision was not my vision. It took a good ten years for Herbert’s novel to relinquish its grip on my imagination, allowing me to appreciate Lynch’s Dune, which I now regard as a worthy adaptation of the novel and a truly great but not unflawed film.

Lynch’s Dune was a critical and commercial flop. Lynch’s lack of creative control over the project left a deep bitterness, which is why there will probably never be a director’s cut, even though Universal has offered Lynch the opportunity. But Dune was still very good for Lynch’s career. It was his first big-budget film, and his director’s fee allowed him to hire his own staff, which played an important role in supporting all of his subsequent creative efforts. Moreover, Lynch’s deal with Dino De Laurentiis was to do two movies: Dune, under De Laurentiis’ control, and a second one, under Lynch’s creative control, which became Blue Velvet, the quintessential David Lynch film. Even the failure of Dune was probably good for Lynch in the end, for had it become a big-budget sci-fi blockbuster, Lynch might have been sucked into creating more conventional Hollywood fare at the expense of his own unique vision. Indeed, before the failure of Dune, Lynch was scheduled to direct two sequels, Dune Messiah and Children of Dune.

As a rule, science fiction is progressivist, whereas fantasy literature is reactionary. Frank Herbert’s Dune saga—which eventually sprawled into six volumes—is the notable exception to this rule, for Dune is one of the most reactionary works of the human imagination. Herbert believed that feudalism, not liberal democracy, was the social system best adapted to mankind’s ascent to the stars. Feudalism was a decentralized system adapted to a society in which population centers were widely separated and in which transportation was costly and slow. Such conditions no longer exist on Earth, but they certainly would pertain between inhabited planets scattered throughout the galaxy. The exploration and settling of the universe is a project requiring immensely long time horizons, which are characteristic of medieval institutions—dynasties, holy orders, guilds—but absent in liberal democracies, in which few people plan past the next election cycle.

Herbert also imagined other ways in which advanced technology would lead to the recurrence of archaic values and ways of life. For instance, in the distant back story of Dune, mankind had been enslaved by its own creations: artificial intelligence and robots. But the machines were overthrown in a massive religiously-inspired revolt known as the Butlerian Jihad, which created a syncretic religion combining elements of Christianity and Islam, as well as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism.

Artificial intelligence was banned, forcing mankind to develop its own mental and spiritual powers. For example, “mentats” used highly developed mnemonic and calculative techniques to become “human computers.” Genetic engineering was also banned, forcing mankind to adopt selective breeding projects—spanning millennia—to improve the human race.

Herbert mentions three hierarchical, initiatic orders: the Bene Gesserit sisterhood, which practiced eugenics; the Spacing Guild, which developed prescient navigators for space travel; and the Bene Tleilax, which trained mentats, created clones, and developed the arts of mimicry to unimaginable heights or depths. (“Bene Gesserit” is a Latin motto that can be interpreted as “well born”—i.e., “eugenic.” It might also be meant to bring the Jesuit order to mind.)

In addition to psychic powers, mnemonic tricks, and eugenics, the Bene Gesserit and Bene Tleilax also used the techniques of “prana-bindu yoga” to develop superpowers or siddhis. For instance, in Dune, the Bene Gesserit practiced the “weirding way” of battle, a form of martial arts. They perfected “the voice,” the power to make their commands irresistible. They also developed minute conscious control of the body’s involuntary and voluntary muscle systems alike. They even had the power to reflectively analyze and control the body’s chemical processes. To normal people, of course, it all seemed like magic, hence the Bene Gesserit were widely disdained as “witches.”

Not only did Herbert envision technology—and its rejection—bringing back sorcery, he imagined how it might bring back swordplay as well. Atomic weapons had been banned, with planetary destruction as the penalty for breaking the pact. Laser-like weapons had been neutralized by the invention of shields. When lasers contacted shields, the result was an immense explosion that would kill both parties. Shields also neutralized projectile weapons like guns. But a slow blade can penetrate a personal shield. Thus high technology has returned us to a world of hand-to-hand combat with swords and daggers.

Herbert’s Dune universe is thus an example of what French New Right thinker Guillaume Faye called “archeofuturism”: a combination of futuristic technology and archaic values, social forms, and practices. One could say the same about Star Wars, of course, but George Lucas was simply riffing—or ripping—off Herbert, from the galactic empire to initiatic knightly orders, down to desert planets and even spice mining, although without Herbert’s deep thinking about how such things could all hang together.

Now this is just the merest sketch of the world that Herbert conjures up in Dune, and it is an enormous challenge to recreate this world—and a story within it that sprawls over more than 400 densely printed pages—into a movie of manageable length. But Lynch does a superb job.

A beginning, we are told in the opening narration, is a delicate time. The novel begins with an old witch, the Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam of the Bene Gesserit, arriving at castle Caladan to test 15-year-old Paul Atreides, the son of the reigning Duke Leto Atreides. Stripped of any mention of space travel, of course, this could be a scene from a fantasy novel. It would be an interesting cinematic bait and switch to see just how deep one could go into the story before revealing that it is science fiction set in the distant future.

Lynch’s dramatization of this scene is one of the best sequences of the film, but it is not how he begins. First, there is a narration by the Princess Irulan, whose words actually begin the book, for the chapters usually begin with epigraphs drawn from her own books on the story Herbert is telling. Irulan establishes straightaway that this is a science fiction movie. The time is the distant future, where the known universe is ruled by the Emperor Shaddam IV, her father. In this time—Irulan almost says “in this period”—the most precious substance in the universe is the spice mélange, which extends life, expands consciousness, and is vital to the spacing guild which knits the empire together. The sole source of the spice is the planet Arrakis, also known as Dune, which is the home of the Fremen, an oppressed and marginalized desert-dwelling people who believe in the prophecy of a messiah or mahdi who will lead them to freedom.

The setting of Dune of course brings to mind the deserts of the Middle East. The Fremen are Arabs. The spice is oil. Arrakis sounds like Arabia + Iraq. Shaddam even sounds like Saddam Hussein, who wasn’t a force when the book was written. The distant and corrupt empire could be Byzantium at the time of the rise of Islam or the Ottoman empire at the beginning of the 20th century. Moreover, the story of Paul Atreides stirring up a Fremen revolt against the Imperium has parallels that are worth a closer look to the story of T. E. Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia.

The Fremen have many Arabic loan-words and Islam-derived beliefs. They practice circumcision. But, rather disturbingly, Herbert envisions these as part of the general fabric of the galactic empire and its syncretic religion. Indeed, in the final two novels, Heretics of Dune and Chapterhouse Dune, Herbert reveals that the Bene Tleilax practice an esoteric form of Islam, taking Muslim misogyny to truly monstrous extremes. But the Bene Gesserit are well-versed in Islamic lore too, although they merely regard it as a topic of study and a tool of statecraft.

After Irulan’s narration and the opening credits, another narrator summarizes “A Secret Report within the Guild,” concerning a plot that might jeopardize spice production, which establishes that Arrakis is the source of the spice, Caladan is the home of the Atreides, Giedi Prime is the home of the Harkonnen, and Kaitain is the capital of the known universe. Frankly, this narration strikes me as clumsy. Can you name another science fiction movie that utilizes it? The names of planets can simply be introduced in passing, as part of the dialogue, or overlaid on the screen (as Lynch later does anyway with Caladan and Giedi Prime). Both narrations are undramatic ways to establish in advance information that Herbert himself introduced quite successfully in the story itself, and Lynch should have just been confident enough of Herbert’s skill and his own to do the same thing.

The first actual scene of the movie is one of the most iconic: the audience of Shaddam IV with a third stage Guild navigator. This scene is entirely Lynch’s invention, although it was inspired by a very different audience with a Guild navigator in Herbert’s sequel, Dune Messiah. Visually, the scene is both sumptuous and surreal, although the Guild navigator seems rather fake and mechanical.

My favorite touch is the departure of the Guild navigator’s locomotive-like tank, which, like a great metallic slug, leaves behind a trail of orange spice slime, some of which is perfunctorily hoovered up by his retainers, who shuffle along dressed in shapeless black boiler suits hiding who knows what mutations. Before they depart, the retainers look back at the Emperor from the doorway, the lintel of which bears the words “Law is the Ultimate Science,” and we hear what sounds like an electronic raspberry before they turn and follow the tank.

In terms of the plot, the audience scene gives the Emperor the opportunity to explain his plot, which is also a good part of the film’s plot. The Emperor feels threatened by the popularity and growing military power of the Atreides of Caladan. To destroy them, the Emperor has ordered them to take control of Arrakis, a prize rich enough to lure them off the security of their home world and onto alien soil, where they will be vulnerable to an attack from their hereditary enemies, the Harkonnens, the former rulers of Arrakis, who will enjoy the secret aid of the Emperor’s elite Sardaukar troops.

Ironically, the Emperor is sending the Atreides into the one place in the universe where the harsh environmental conditions have created a fighting force capable of defeating the Sardaukar—namely the Fremen, who, unknown to the Imperium, exist in vast numbers and have effective control of Arrakis, and with it the spice, the most precious commodity in the universe.

The Fremen have been quiet under Harkonnen rule, stealthily pursuing a project of terraforming Arrakis into a more livable world. The Harkonnens are basically merchant princes. They measure power in terms of wealth and treat Arrakis simply as a colony to be exploited. They regard soldiers simply as mercenary muscle, Pinkertons to keep the workers in line. Thus they have overlooked the Fremen and have no idea of their numbers and military potential.

One of the themes of the novel, which did not make it into the final cut of the film, is that the leader of the Harkonnens, Baron Vladimir, for all of his Byzantine plotting, is really rather thick, because he is blind to the whole realm of warrior virtue and how it is cultivated. He is entirely a creature of his appetites, which are monstrous. He has grown so fat that he has to be buoyed by suspensors to move around. He is the embodiment of the bourgeois ethos of hedonism and preferring dishonor to death. Lynch’s characterization intensifies these traits almost to the point of parody. Lynch’s Baron—played by Kenneth MacMillan with unfortunate traces of a New York accent—is not only fat, but also covered with hideous suppurating sores. His doctor is always near, to keep his carcass alive for further pleasures.

The Emperor and his close confidant Count Fenring suspect that the Baron wishes to use Arrakis to create fighting men, because that is what they would do. The Emperor simply refuses to believe that the Baron has overlooked the superb fighting skills of the Fremen. But such matters simply did not occur to him.

The Atreides, however, are very different. They are a martial elite, tracing their descent from the ancient house of Atreus. They measure power in terms of the size, the power, and especially the loyalty of the military forces they command. The Atreides are renowned for their ability to inspire loyalty from their men by giving it to their men. They are masters at the delicate art of creating camaraderie and brotherhood within a hierarchical, military order. The Harkonnen’s soldiers will kill for money. The Atreides and the Fremen and the Sardaukar will die for honor. All the Fremen need for them to rise up against the Imperium are a catalyst and a leader—both of which are provided by the Emperor’s plot.

Another important element established in the audience scene is that in the Dune cosmos, the leading institutions of society—the ruling houses, the Bene Gesserit, and the Spacing Guild—have worked together for a very long time while keeping immense secrets of great importance from one another. Only the Emperor is allowed to see the Guild navigator. The ruling houses, moreover, are kept in the dark about the ultimate aims of the Bene Gesserit, even though they accept their sisters as wives, concubines, and mothers of their heirs. Indeed, in all six Dune books, Herbert never really tells us what the Bene Gesserit’s goal is, beyond serving humanity. To maintain such levels of secrecy in vast organizations carrying out plans that span thousands of years presupposes remarkable levels of both idealism and discipline.

The guild navigator tells the Emperor that they want young Paul Atreides, the ducal heir, killed. This too is not in the book, but it gives a motive for Reverend Mother Mohiam’s visit, which begins the book. It is an unnecessary move. Herbert’s beginning was fine as it is. But Lynch wished to present the Guild as the ultimate wire-pullers, whereas for Herbert they are just one player.

But there are three more scenes before we actually get to the test. The first is cleverly compounded out of three separate scenes in the novel. It introduces Paul as well as three Atreides retainers: the mentat Thufir Hawat (Freddie Jones), Doctor Wellington Yueh (Dean Stockwell), and sword master Gurney Halleck (Patrick Stewart). All three characters are wonderfully realized. Paul is played by Kyle MacLaughlin, one of Lynch’s favorite actors (Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks), who in truth is a bit old to depict the fifteen-year-old of the novel. But Herbert had a disturbing pattern of creating sexually precocious teens and even pre-teens, which simply cannot be portrayed on screen, necessitating casting older actors.

Paul is introduced studying what today look like large, clunky computer tablets. This sequence is perhaps the clumsiest in the film. As Paul reviews the relative positions of Caladan, Giedi Prime, and Arrakis (all unnecessary given the Secret Report), little voices insert bits of background information. For instance, we are told that Bene Tleilax is where mentats come from, that they are human computers, and one can know them by their red-stained lips. We are also told that Baron Harkonnen has vowed to destroy House Atreides and steal the ducal signet ring for himself.

Was Lynch unable to work this information into the script in a more natural way? And why include the detail about the signet ring at all? This is not Lord of the Rings. There is no magic in Leto’s signet. If we really needed to know about mentats, why not include the scene where it is revealed that Jessica and Thufir have been training Paul to be a mentat, without him even knowing it? This bit of information is actually quite relevant to the development of Paul’s character as the story unfolds.

Another oddity in this sequence is the introduction of the “weirding modules,” which is also a Lynch invention. In the novel, the weirding way of battle is a Bene Gesserit martial art. It is a yogic superpower. In Lynch’s hands, it becomes a weird-looking hand-held device that turns sound into a killing force. It seems likely that Lynch introduced this concept simply to pander to sci-fi fans who expect laser guns, which Herbert took pains to replace with swords and daggers. (Moreover, the Sardaukar use lasers in the final battle scene, anyway.)

It would have been far more faithful to Herbert to depict the weirding way in the manner of Chinese wuxia movies like Hero and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which have just as much audience appeal as laser battles, anyway. This is essentially how it was treated in the Sci-Fi Channel productions of Dune and Children of Dune. Frankly, such an approach would have made Lynch’s climactic battle scene far more interesting. Let’s hope Denis Villeneuve is taking notes.

Then, after two brief scenes, the first introducing Duncan Idaho (Richard Jordan), the second introducing Paul’s father, Duke Leto (Jürgen Prochnow), we finally get to the test. Lynch’s handling of this scene is truly virtuosic. His script masterfully distills everything essential from Herbert’s text, and the settings, casting, and performances are all first rate.

Welsh actress Sian Phillips (Livia in I, Claudius) is a superb Reverend Mother, capturing every facet of Herbert’s character: her steely ruthlessness and fanaticism in the pursuit of her ideals as well as her very personal attachments, disappointments, and hopes—and even such bizarre and disconcerting details as her metal teeth.

Francesca Annis plays Paul’s mother Jessica, a Bene Gesserit sister who broke her vow to the order to bear only daughters to the Atreides, bearing Paul instead. Annis looks exactly like Herbert’s description of Jessica: tall, willowy, beautiful, with reddish-brown hair and an aristocratic bearing that makes everyone think she is high born, when in fact she was the illegitimate child of a Bene Gesserit of unknown rank, and her father’s identity was kept secret from her. (Which is just as well, because he turned out to be Vladimir Harkonnen.) A sign of the great care that went into casting is that Kyle McLaughlin actually looks like he could be the son of Francesca Annis and Jürgen Prochnow.

So why are the Guild and the Bene Gesserit interested in young Paul Atreides? For 90 generations, the Bene Gesserit have been running a selective breeding program, blending the best bloodlines of the empire, both aristocratic and common (introduced through Bene Gesserit wives and concubines), to produce a superman, whom they call the Kwitsatz Haderach, the “shortening of the way,” the one who can be many places at once.

The Bene Gesserit have perfected a way of tapping into and passing on the memories of their maternal ancestors and fellow sisters. This presupposes that memory is somehow stored in a realm outside the individual mind that can be tapped into by different minds—akin to the Theosophical idea of the “akashic records” encoded in the ethereal realm. This is also the presupposition of the idea introduced in Dune Messiah that a clone (or “ghola”) can recover the memories of the past physical incarnations of its genotype.

But the Bene Gesserit cannot access male ancestral memories. The Kwisatz Haderach, however, will be able to do so, in addition to female memories.

The Bene Gesserit, however, are not interested simply in mastering the past. They also wish to see into the future. Like the Guild’s navigators, they gain prescience by consuming the spice. The Bene Gesserit clearly expect the Kwisatz Haderach to share in this power as well, since the Reverend Mother asks Paul quite pointedly if he has prescient dreams.

Thus the Kwisatz Haderach will be a Janus figure, both surveying the collective memory of mankind and peering into the future. Such knowledge would bring enormous power, to the Kwisatz Haderach himself, and to the sisterhood that controlled him.

After the test scene, Lynch takes us to the Harkonnen planet Giedi Prime. Lynch’s depiction of Giedi Prime is his own invention. It is a hideous industrial hellscape, built over bubbling black filth that is a nod to the “matmos” of another sci-fi flop, Barbarella, also produced by De Laurentiis. Black smoke belches from the mouth of a huge, fat face, perhaps a nod to H. R. Giger’s design for the Harkonnen keep for Alejandro Jodorowski’s abortive Dune adaptation. Unlike the novel, Lynch’s Baron does not live in sybaritic splendor. His palace looks like a factory or a slaughterhouse, a maze of roofless green-tiled rooms lost inside a vast industrial box. (Herbert actually incorporates Lynch’s depiction of Giedi Prime into Heretics of Dune.)

When we enter the Baron’s presence, we first hear a humming, then the bubbling of the matmos, then a sickening slurping sound. The Baron’s grossly fat body lolls on a chair while his doctor sucks gunk out of the sores on his face, aided by retainers whose ears have been sewn shut and whose vision is restricted by hideous goggles. The Harkonnens stamp their tyranny into the very flesh of their servants. Indeed, every Harkonnen subject has a “heart plug” installed that allow him to be murdered with no more effort than flipping a switch.

The scene also introduces the twisted mentat Piter De Vries, played by Brad “Wormtongue” Dourif, as well as the Baron’s nephews Feyd (Sting) and Rabban (Paul Smith). Jack Nance plays the Baron’s henchman Nefud. After Piter pedantically explains the plan to destroy the Atreides to Feyd and Rabban, the Baron—half devil, half child—exultantly activates his suspensors, shooting into the air like a whirring blimp while laughing manically. Then he descends, painted toenails delicately en pointe, pausing a moment to bathe in the matmos drizzling down from the glowglobes in his audience chamber, then pounces on a terrified twink, pulling his heart plug and bathing in his blood. It is a bit much for most people. But one has to give Lynch credit. I can’t think of a grosser and more loathsome villain in all of cinema.

The Atreides departure for Arrakis is a highly imaginative sequence. The costumes and accouterments of the Atreides bring to mind the British Empire in the early 20th century, right down to their pug. (When Gurney Halleck charges into battle against the Harkonnens, he carries the pug with him. In the final scene of the movie, the little dog reappears, having somehow survived the Harkonnen attack and subsequent years of guerrilla warfare in the desert.)

The Guild spaceship, with its ornate entrance and mysterious, Gigeresque innards, is intriguing. Lynch’s machine and ship designs in Dune do not look like extrapolations on present-day technology. They are not sleek and “space age,” but weirdly clumsy and clunky, covered with tubes, pipes, wheels, and spikes that look archaic, not futuristic. (Some of them are apparently dwarf-powered.) It is frankly impossible to envision how they might work, which adds to their uncanniness.

A historian of design needs to explore the question of whether we are witnessing the birth of the Steampunk aesthetic in Lynch’s Dune. It makes sense, because immediately before Dune, Lynch directed The Elephant Man, which is set in Victorian London. There are even some design continuities between The Elephant Man and Dune, for instance the gas wall sconces in The Elephant Man have equivalents in the Emperor’s throne room. The worst aspect of Lynch’s design is dressing the Sardaukar troops in shapeless hazmat suits.

Many people complain about the spaceship effects in Dune, and on DVD and Blu-ray, they do look bad. But I have seen Dune in the theater, and they look just fine on the big screen. George Lucas, of course, could have done better, but that’s the only thing he could have improved.

The sequence in which the Guild navigator “folds space” is bizarre, but how would you depict it? First, it should be noted the “folding space” is another Lynch invention. Herbert only ascribes the power of prescience to the Guild navigators. Second, Lynch’s depictions of the navigation sequence and Paul’s visions are based on Herbert’s descriptions. In the novel, after Paul takes the water of life and is finally transformed into the Kwisatz Haderach, Jessica leads Paul into the place where Reverend Mothers—women—are terrified to go, “a region where a wind blew and sparks glared, where rings of light expanded and contracted, where rows of tumescent white shapes flowed over and under and around the lights, driven by darkness and a wind out of nowhere.”

Once the Atreides are on Arrakis, two scenes stand out for their faithful and inspired adaptation of the novel: the spice harvesting sequence and the attempt to assassinate Paul with a hunter-seeker. The spice harvesting sequence introduces the imperial planetologist, Dr. Liet Kynes, a natural aristocrat and the true leader of the Fremen (superbly realized Max von Sydow). It also gives us our first glimpse of the sandworms of Arrakis, Lynch’s trifold design for which follows Herbert’s description of the sandworm mouth as opening like the petals of a flower. Finally, it establishes an important aspect of the character of Duke Leto: he values loyalty more than money, and the loyalty goes both ways, to his men and from them. In the interests of economy, Lady Fenring’s conservatory, a long dinner party, various short military conferences, and a subplot about Hawat’s suspicions of Jessica are omitted. A conversation between Jessica and the Shadout Mapes (Linda Hunt) was filmed but cut.

Dr. Yueh’s betrayal, the Harkonnen attack, the death of Leto, and Paul and Jessica’s escape are all quite faithful to the book and realized in a compelling and often quirky manner. (I especially enjoyed Piter’s strange hand gestures in his conversation with Nefud.) But in the interest of time, Lynch abridges Paul and Jessica’s flight. The capture of Hawat and the deaths of Duncan Idaho and Dr. Kynes are also abridged, to no great loss.

Lynch’s treatment of the second part of Dune, Paul and Jessica’s adventures with the Fremen, however, is highly abridged. It turns out that Lynch had actually filmed a number of scenes that were later cut. First, there is Paul’s duel to the death with the Fremen Jamis, which leads to the scene where he is given the name Usul and chooses the name Paul Muad’dib. Then there is the deathstill scene, removing the water from Jamis’ body, which leads to the scene where Paul and Jessica are shown a vast Fremen water cache. There are also scenes where Chani learns of the death of her father, Dr. Kynes, and the Fremen drown a tiny sandworm to produce the water of life. These scenes really should be restored in a director’s cut. They would allow the Fremen world to breathe a bit and disclose some of its wonders. Theater running times are no longer an issue, and every fan of the novel and Lynch film would rejoice.

Everett McGill, who also appeared in Twin Peaks and The Straight Story, plays Stilgar, the Fremen leader. Oddly, McGill manages to make his voice sound like a dubbed Italian film from the 1960s. Sean Young plays Chani.

Aesthetically, the second half of Dune is the least satisfying. Lynch’s depiction of the deserts and mountains of Arrakis, as well as the underground lairs of the Fremen, are frankly ugly and often unpleasantly dark and murky, often verging on the unintelligible. They fail miserably at capturing the sublime splendor of the desert in Herbert’s descriptions. One wishes that Lynch had watched Lawrence of Arabia before shooting Dune, or simply visited the high deserts of Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico for some inspiration. Let’s hope that Denis Villeneuve does not neglect the opportunity to include some dazzling nature photography in his forthcoming adaptation. It is a cheap and easy way to enchant moviegoers.

The third and final part of Dune depicts Paul and the Fremen’s defeat of Shaddam and the Harkonnens and Paul’s installation as the new Emperor. Generally, Lynch’s adaptation is quite faithful. There are some engagingly quirky and bizarre touches, such as the Sardaukar generals, a racially diverse collection of scarecrows and tin woodsmen with metal plates in their heads, or the Emperor’s strange rotating control center, where Shaddam and his generals rain down fire on their attackers as if they are playing a video game. The worst special effects in Dune are in the climactic battle, which has dreadful process shots and bizarrely skewed color contrasts.

The final scene, in which Paul defeats Feyd in hand-to-hand combat, is brilliantly done. Sadly, it was heavily cut. The touching death of Thufir Hawat was removed, which rendered somewhat pointless the scene on Giedi Prime where the captive Thufir had a heart-plug installed and is told that a poison has been introduced into his body in order to make him dependent on the Baron for the antidote. The terms that Paul dictates to Shaddam, including marrying his daughter Irulan, are also cut. Finally, Lynch omitted the strange but moving final words of the novel, in which Jessica reassures Chani that they may bear the rank of concubine, but history will remember them as wives.

Instead, Lynch ends with another of his inventions: a miracle. Paul causes rain to fall on Arrakis. Herbert himself chided Lynch on this ending, claiming that Paul was not actually a messiah. He was just pretending to be one. But in fairness to Lynch, Dune is the story of a superman who is taken as a messiah. If the messiah could not make rain, perhaps the superman could. Furthermore, both the project that bred Paul and the prophecy he fulfilled were set in motion by the Bene Gesserit. The confluence of these schemes on Arrakis might merely be a freak accident, but readers can also be excused for seeing it as some sort of Providence. Herbert himself makes such a reading possible with his genre-bending fusion of science fiction and fantasy tropes.

Irulan’s narration also speaks of how Fremen prophecy predicted Paul Muad’dib’s ascension would bring peace and love to the galaxy. This comes off as bitterly ironic to the readers of the novel, because there Paul knows better. His prescient vision shows only civil war and untold suffering as the Fremen spill off-world and subdue the cosmos in a new jihad.

There is no reason why Lynch could not keep his ending and restore Herbert’s and the other deleted bits of the final scene in a director’s cut.

What lessons should Denis Villeneuve learn from the successes and failures of Lynch’s Dune? First and foremost: if Herbert’s novel was good enough to enthrall millions of readers over more than fifty years, a faithful film adaptation will be good enough to produce a classic beloved by millions of viewers. Second, incorporate nature photography for the desert scenes. Nature is more beautiful than anything that can be created with CGI or on soundstages. Third, don’t over-explain. Lynch’s greatest mistake was not to follow Herbert’s example of merely intimating the backstories while unfolding the main story. Of course, this technique filled the readers’ minds with questions. But that is one of the reasons we just kept reading. There’s nothing wrong with mystery, after all.

The main cause of Lynch’s tendency to over-explain was lack of faith in the novel and in the audience. It is hard to tell how much of this was Lynch’s own mistake and how much was a result of pressure from De Laurentiis. We can infer that the latter played a large role from watching the extended version of Dune that De Laurentiis produced for television after the movie’s theatrical failure. Lynch insisted that it not bear his name. This production contains a great deal of footage that Lynch cut, as well as even more back narration, using extremely ugly drawings. The clear intention was to make Dune intelligible to complete morons, the kind of people who could not see a simple cut between locations and infer that someone had traveled between them.

Viewing this abomination is a painful experience. Many good scenes were dropped and should be restored to a director’s cut. But also a great deal of fat was trimmed, particularly in the audience scene, where every single cut removed even more over-explaining—adding back in some of the atmosphere of mystery and wonder that made Herbert’s Dune a classic. If only Lynch had gone further. Lynch’s Dune is not a classic like the original novel, but it remains superior to the Sci-Fi Channel mini-series, which is far less artful, while remaining much more faithful to the book. If Denis Villeneuve manages to combine artfulness and fidelity, he may well surpass them both.

The Unz Review, April 16, 2019