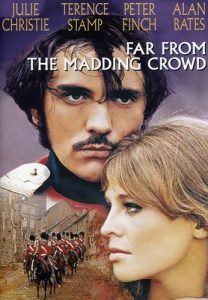

Far from the Madding Crowd

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledJohn Schlesinger’s 1967 adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s 1874 novel Far from the Madding Crowd should be a universally recognized cinema classic. But although it received generally positive reviews and did well in England, today it is virtually unknown, even among my friends who are film buffs.

I am going to comment on the movie only, not the book, which I have not read. I am told, however, that the film is a fairly faithful adaptation. Since the film is more than 50 years old, there will be spoilers.

Far from the Madding Crowd is set in the West Country of England in the 1860s. A young shepherd, Gabriel Oak (Alan Bates at his handsomest), proposes marriage to Bathsheba Everdene (Julie Christie at her loveliest), who is apparently an orphan living with her aunt on a neighboring farm. They would make a handsome couple. Gabriel is clearly intelligent, hard-working, and responsible. He pleads his case well. But Bathsheba declines, because she does not “love” him, and to her mind, it is as simple as that. One has to wonder, though, what exactly she means by love, and why it features so prominently in her decision, since rural farm folk tend to be very pragmatic about such matches. She even urges Gabriel to think pragmatically and find a woman with some capital.

Soon Bathsheba moves away, and Gabriel tries to put her out of his mind. But when Gabriel’s flock is killed in a ghastly accident, he is forced to up stakes and seek employment on another man’s farm. In his search, he comes across a farm where a fire is sweeping through the hayricks. The farmhands are ineffectual in fighting the fire, so he takes charge and saves the farm. He then discovers that the farm belongs to Bathsheba. Her uncle, a wealthy farmer with no children of his own, has willed it to her, and she is now wealthy. She recognizes Gabriel’s value and employs him.

When Bathsheba fires the farm’s bailiff for thievery, she decides that she will manage the farm herself. She is, in short, one of those “headstrong, independent women” that every year advertisers and journalists tell us are brand new, not like the shrinking violets and clinging vines of last year. Apparently, this radical break with the past has been happening every year at least since 1874, when the novel first appeared.

However, unlike today’s strong, independent woman stories, Far from the Madding Crowd is not a feminist morality play. Quite the opposite. Hardy shows that Bathsheba’s independence is actually a source of great suffering for herself and the people around her. As an orphan, Bathsheba has nobody to look out for her, especially to give her guidance in matters of the heart. Her aunt did try to care for her—deflecting Gabriel’s advances, which strikes me as a bad choice. But she might have expected her niece to become wealthy and thus to be able to aim higher.

However, once Bathsheba leaves her aunt and is installed as mistress of a large and valuable farm, she has no economic necessities that might prompt her to make a pragmatic match, which allows her to let her feelings decide. Moreover, she has no family or friends of her station who can tell her unpleasant truths that she needs to hear. In one scene, for instance, he basically orders a servant girl to lie to her about the history of a cad with whom she becomes infatuated, leading to disaster.

The basic message of Far from the Madding Crowd is that empowering a person who lacks wisdom and maturity is a bad thing. Indeed, empowering such people actually cuts them off from the sources of wisdom and maturity that they need. But it is not just an anti-feminist message, although in this case the primary victim is a woman. It is an anti-individualist message, for the whole thrust of individualism is to empower people to make their own decisions, regardless of wisdom and maturity.

Gabriel settles in on the farm, where he consistently demonstrates manly self-discipline, conscientiousness, and technical mastery. He is, in truth, a natural leader—an alpha male—and slowly Bathsheba gives him more powers and responsibilities. He’s a rock. He’s always there for her. And apparently there’s nothing the least bit loveable or sexy about it from her point of view.

One spring day, Bathsheba finds an unused valentine in her dead uncle’s papers. (It is odd that a childless old man had a valentine to begin with, but it makes sense it was never used.) On a whim, Bathsheba writes “Marry Me” on it and sends it to Mr. Boldwood, the even wealthier farmer next door.

Boldwood, brilliantly played by Peter “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it anymore” Finch, is a bachelor in his late 40s who is instantly smitten with the beautiful Bathsheba and of course wants to marry her. He too would be a fine catch. A bit old, but fit and good-looking, with extensive resources and proven skills in farming and business. One imagines Bathsheba’s old aunt would have pleaded Boldwood’s case.

But none of that seemed to occur to Bathsheba. The proposal was only a joke. She cannot marry him because she does not love him. Boldwood, however, presses her not to refuse him outright but to give him her decision at harvest time. Out of weakness, Bathsheba agrees, stringing the poor man along for months while he hopes in vain that she will become a bit more pragmatic or perhaps even grow to love him.

It was, of course, wrong for Bathsheba to send the proposal in the first place. Her old aunt would have quashed the idea immediately, and Bathsheba would probably have assented. But her only peers at the time were farmgirls who worked for her and would not have felt comfortable giving her advice even if they had known better. A mature and sensitive woman would never have trifled so callously with the old bachelor’s heart.

Bathsheba was also wrong to string Boldwood along. A more mature woman would have admitted her mistake, apologized sincerely, and flatly refused him. But then again, a more mature woman would not have made the mistake to begin with.

But Boldwood too was at fault. He was too smitten to grasp Bathsheba’s immaturity and simply would not take no for an answer. Like Gabriel, he should have simply tried to put her out of his mind.

Still, Bathsheba might well have ended up marrying Boldwood were it not for the appearance of cavalry sergeant Francis Troy, played by Terence Stamp. Although his face entirely lacks beauty or character, the fact that he is tall, dashing, and wears a uniform makes him irresistible to women. Troy, however, is a cad, with a full suite of what the manosphere calls “Dark Triad” traits—narcissism, sociopathy, and manipulativeness—which women commonly mistake for healthy alpha male traits. Troy’s lines are among the most brilliant in the script, and Stamp is superb at bringing this loathsome character to life.

Before Bathsheba came on the scene, Troy had seduced, impregnated, and then abandoned one of the farm girls, Fanny Robin. He actually agreed to marry her. But it was an impromptu affair, and when she went to the wrong church at the appointed time, his vanity was so inflamed that he broke the engagement. Fanny mysteriously disappears, and later we learn it was not just due to being jilted but also to hide the shame of being pregnant.

In any case, Troy soon had a much richer and prettier prospect: Bathsheba herself, whom he proceeded to woo with flattery, teasing, and dangerous displays of swordsmanship. The swordplay scene is utterly ridiculous, but Christie is entirely believable in communicating her character’s hopeless, irrational infatuation with Troy. She truly does “love” him. (The film credits include a folk song consultant, a sword master, and a horse master, so of course I found it irresistible.)

In one of the best scenes of the film, Boldwood tries to bribe Troy into marrying Fanny and leaving Bathsheba to him. Troy toys with Boldwood, then announces that he is too late, for he has married Bathsheba that very morning. Boldwood is crushed.

The honeymoon does not last long. Troy has apparently left the military. He is immediately accepted as lord of the manor, but he has no knowledge of farming or interest in responsibility. In a scene that beautifully illustrates his character—or lack of it—he regales the adoring farmhands with bawdy military songs while drinking them under the table. Meanwhile, a storm brews up, and when Gabriel tries to get some of the farmhands away from the party to secure the hayricks from being blown away, he is rebuffed by Troy who does not want to lose his audience. It is classic narcissist behavior. So Gabriel and Bathsheba herself struggle in the storm, soaked to the bone, to save the farm from loss while Troy’s revelries continue.

Troy also enjoys gambling over cockfights, and his narcissism makes it easy for his opponents to keep raising the stakes, lest he lose face. It isn’t his money that he is losing anyway.

Another extravagance is a large musical clock, which features a trumpeter in the same cavalry uniform as Troy wore. The design of the clock does not seem to fit with the style of the period, cleverly suggesting Troy’s essential childishness and lack of taste.

Bathsheba is willing to suffer quite a lot because she is “in love” with Troy. But things come crashing down when a very pregnant Fanny Robin shows up at the farm asking for Troy’s help, then promptly dies in childbirth. When the coffin is brought to the farm for burial, Gabriel hides the fact that it also contains a baby. But Bathsheba opens the coffin and discovers it. Troy then walks in, and his behavior is utterly galling. Suddenly, he seems to be filled with love and remorse for Fanny, kissing her dead face as Bathsheba looks on in horror, then demands that he kiss her instead. Troy leaves the farm, but erects an expensive tombstone for Fanny in the manor’s churchyard. The grave is below a gargoyle waterspout, and the first rains of fall turn it into a mud pit, brilliantly underscoring the true nature of Troy’s behavior. He is simulating love and dejection merely to spite Bathsheba. Troy then goes to the ocean, undresses, and swims out to sea.

Bathsheba is at the corn exchange when she is told that her husband has apparently drowned, his body swept out to sea. She faints dead away, but her ever-faithful orbiter Boldwood is there to catch her. After a decent period of mourning, Boldwood begins courting her again. Because there is no body, Bathsheba must wait six years before she is free to marry again. Boldwood tells her he will wait. Again, Bathsheba wants to say no, but he again pressures her to wait until Christmas to decide.

As Christmas approaches, Boldwood prepares a lavish party, confident that he will be announcing his engagement. He seems positively giddy, and it is impossible not to feel for him. But then disaster strikes. After Bathsheba has accepted his ring, but before they can announce their engagement, Troy reappears. He has faked his death. But having heard of Bathsheba’s prospective engagement, he returns out of spite to assert his marital rights. Bathsheba is shocked and refuses to follow him. So Troy begins to manhandle her. Then we hear a shot. Troy falls dead on the stairs. Boldwood stands with a rifle.

Then we witness one of the most wrenching tragic climaxes since Sophocles. Bathsheba does not fly to Boldwood’s side to thank him for rescuing her. She breaks down in tears over her beloved Frank. Now Boldwood sees the terrible truth. By showing up at the party, Frank revealed to everyone that he was a complete monster. But that did not matter, because Bathsheba “loved” him. Boldwood is a genuinely noble man, but it doesn’t matter, because she didn’t “love” him. Justice doesn’t enter into this at all. Boldwood looks on, in utter horror, at the abyss of irrationality into which he has flung his life. For he will hang for this, for a love that was entirely one-sided and illusory.

Two men—one noble, the other base—end up dead, all for a woman of genuine beauty and goodness who was empowered to make catastrophic decisions that destroyed two lives and brought misery to her own.

But Bathsheba eventually recovers. She buries Frank in the same mud pit as Fanny and adds his name to the tombstone. She still has a large and prosperous farm, surrounded by people who feel genuine affection for her, including her ever-faithful and reliable Gabriel, who is there to help her run the place.

But instead of wasting away in Bathsheba’s friend zone, Gabriel decides to move to America. Only then does Bathsheba truly appreciate him. For she can only really love a man who is independent of her. She rushes to stop him. Gabriel says he will stay under one condition. Then, in a gesture that will pierce even the most cynical hearts, he repeats word for word his vision of married life that she had rejected at the beginning of the film. But this time she says yes. It was the right choice. They will raise beautiful children on a happy and prosperous farm.

The movie ends with Gabriel and Bathsheba settling into married bliss. But then the eye of the camera strays over to Troy’s clock, focusing on the soldier in the tower, like a memento mori to remind us that the Troys of the world and the irrational romanticism they evoke will always threaten marriage and family life.

Unz.com [2], April 2, 2019