Go Down, William Faulkner

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled4,880 words

A novelist can have tremendous influence beyond his own time if he depicts major historical trends and invents characters that react in conflicting ways to these trends. If a story is vivid enough, readers might come to identify with or even emulate such characters, since the historical pressures bearing down on them bear down on the readers as well. William Faulkner accomplishes such a feat in his 1942 novel of interrelated short stories, Go Down, Moses.

And this is anything but good.

Boiling Go Down, Moses to its essence reveals how Faulkner effectively wrote the handbook outlining acceptable white opinions on race – on blacks in particular – which remains in effect today. The omniscient narration, presumably told from the author’s perspective, evinces a distaste towards white people and Southern culture in general which at times borders on contempt. Through the character of Lucas Beauchamp (who’s three-eighths white and five-eighths black), Faulkner dips his toe in the murky waters of negrophilia. And through the entirely numinous Sam Fathers (who’s half American Indian, three-eighths white, and one-eighth black), Faulkner propagates the wise, old Indian trope to such an extreme that the character becomes an all-knowing demigod of nature who can read the minds of bears.

In the novel’s central character, Isaac McCaslin, we have white guilt personified. Born in 1867 into a prominent white family in Faulkner’s mythical Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi, McCaslin relinquishes his legacy and birthright. He claims that the American South is “cursed” by the sin of slavery and wishes to do as little as possible to perpetuate its culture and people. By the time of the novel’s close, he’s a wise old codger and childless widower who prefers to remain close to nature through hunting. He also likes to talk about how no man can own land, just as no man can own air or sunlight. It’s all God’s, you see. So it belongs to everyone. He’s the only enlightened white in the book.

Go Down, Moses chronicles the slow decline of the McCaslin family from its slaveholding heyday to its sad, languid final stages in the 1940s – only, this is the white branch. There’s a black branch as well, thanks to old Carothers McCaslin’s dalliances with a slave named Tomey back in the early nineteenth century. This branch is far more vigorous and fecund than the white one, and thus generates greater sympathy from the point of Faulkner’s pen. The first story, “Was,” depicts the crucial antebellum moment when twin brothers Buck and Buddy, the only remaining heirs of the McCaslin fortune (who happen to be committed bachelors pushing sixty), win a poker a game off a neighbor named Hubert Beauchamp. The stakes involved Hubert’s sister Sophonsiba’s hand in marriage to Buck, as well as Hubert’s slave Tennie Beauchamp’s hand in marriage to Buck and Buddy’s slave (and half-brother), Tomey’s Turl.

If you think this is confusing, you should read the source material. And I will get to Faulkner’s confusing writing style soon enough. In the meantime, the takeaway here is that Isaac was only the product of the white union, and Lucas the sixth and last of the black one.

“The Fire and the Hearth,” more of a novella than a short story, takes us to the present day (1941) and concerns old Lucas as he protects his lucrative moonshine business while he hunts for gold on McCaslin property, a portion of which he rents as a sharecropper. Aside from old Isaac, who’s living alone in a small house on a monthly allowance in return for his renunciation of the McCaslin fortune, the only remaining white McCaslin heir is Roth Edmonds, old Carothers’ great-great-great-grandson, who’s now the plantation’s proprietor. Lucas, who’s old Carothers’ grandson and descendent along the male line, feels he should be in charge rather than Roth, who’s descended from a female line. (Faulkner never explains why male lines outweigh female ones in these circumstances, so we must assume it’s a Southern thing.)

Faulkner’s anti-white animus throbs in “The Fire and the Hearth.” First, he makes Lucas the cleverest person in the story. By shrewdly calculating the natures of the people he’s forced to deal with, he’s able to manipulate them to get what he wants. He lies to Roth’s face, steals a mule from him, and gets away with it. He finagles loyalty and labor from his less-than-reliable son-in-law, and he leads a city-slicker salesman on with false promises in order to get a metal detector for almost nothing. The only person who stops him in the end is his wife Molly, who threatens to divorce him.

This, of course, is not so bad per se, given that there are clever blacks and not-so-clever whites in the world. But look at how Faulkner describes Lucas:

Yet it was not that Lucas made capital of his white or even his McCaslin blood, but the contrary. It was if he were not only impervious to that blood, he was indifferent to it. He didn’t even need to strive with it. He didn’t even have to bother to defy it. He resisted it simply by being the composite of the two races which made him, simply by possessing it. Instead of being at once the battleground and victim of the two strains, he was the vessel, durable, ancestryless, nonconductive, in which the toxin and its anti stalemated one another, seetheless, unrumored in the outside air.

Such numinous nonsense. Is there any obstacle that a noble Negro can’t overcome with the aid of a white writer’s poetic prose? Aside from Isaac McCaslin, no white character gets treated with such gravitas in Go Down, Moses. Here’s how the dissipated and effete Roth describes Lucas:

I am not only looking at a face older than mine and which has seen and winnowed more, but at a man most of whose blood was pure ten thousand years when my own anonymous beginnings became mixed enough to produce me.

Twice, Faulkner describes Lucas as a “composite” of thousands of “undefeated Confederate soldiers” as a way of telling the reader that our gallant black is not only more McCaslin than the old man’s white descendants, he’s more of a man than they are as well. But does Faulkner even know what black people look like? It takes a religious suspension of disbelief for a reader to buy that the face of a person who is more than half black can evoke the faces of white Confederate soldiers.

For Faulkner, blood matters. In Go Down, Moses, he brings it up a lot, but never evenhandedly. For blacks or for the otherworldly Indian Sam Fathers, blood is good. It’s a source of nobility and dignity. But for whites, blood is necessarily bad. It’s a source of shame, despair, and weakness. Or it’s worth nothing. Why? Because our Nobel Prizewinning author says so. He writes off a local white sheriff as “a redneck without any reason for pride in his forebears nor hope for it in his descendants.” Roth’s mother, a mysterious woman named Louisa, dies giving birth to him. This is how Faulkner commemorates the tragedy:

It was as though the white woman had not only never quitted the house, she had never existed – the object which they buried in the orchard two days later (they still could not cross the valley to reach the churchyard) a thing of no moment, unsanctified, nothing.

Are white people sociopaths in Yoknapatawpha County? Do they routinely shrug off such devastation? Is human life worth so little to them? Did this woman not have family, friends, or neighbors who would take an interest in the baby’s welfare? Faulkner implies that the answer to all these questions is yes.

Perhaps the most poignant passage in the novel concerns Roth as a young boy who spends most of his days in Lucas’ household, being raised by Lucas and Molly and playing with their young son, Henry. Henry and Roth are best friends, and Roth actually prefers the Negro household to his own. Then, one day, Roth decides that because he’s white and Henry’s black, he must push Henry out of his life forever. It’s a cruel move, and Faulkner handles it well. We all hate rejection, and our heart breaks for the poor innocent black child whom Roth has grown so suddenly to despise.

Of course, for Faulkner, a natural aversion to blacks could not possibly explain such a decision, nor could any specific thing the black individuals did or did not do. No, it was Roth’s blood coming back to haunt him:

Then one day the old curse of this fathers, the old haughty ancestral pride based not on any value but on an accident of geography, stemmed not from courage and honor but from wrong and shame, descended to him.

Got that, kids? If whites are made to feel uncomfortable around blacks, it’s not because of inherent racial differences in IQ or temperament. No, it’s because white people are cursed.

Just as prominent as “The Fire and the Hearth” in this volume is “The Bear.” The story chronicles the hunting life of Isaac McCaslin as a boy and as a young man, and finally gets to the reason why he renounces his birthright. The narrative takes place more or less over a decade, from the late 1870s to 1888, when Isaac turns twenty-one. Ostensibly, “The Bear” is Isaac’s coming of age story, but it also contains fifty-eight pages of wordy, tedious, and often baffling exposition that has little to do with a bear, and could have been sequestered into its own story and cut by two-thirds without anyone raising complaints. Why would they, when sentences in it can run for many hundreds of words?

Faulkner lays out the principals in “The Bear” in its first paragraph: Isaac, Sam Fathers, a gigantic white named Boon Hogganbeck, the bear (named Old Ben), and a massive, malevolent hunting dog named Lion. Staying true to the hemoglobic theme of the novel, Faulkner informs us that in Boon, “some of the blood ran which ran in Sam Fathers, even though Boon’s was a plebeian strain of it and only Sam and Old Ben and the mongrel Lion were taintless and incorruptible.” Boon’s white blood, of course, is not worth even noting.

Faulkner is anything but unsubtle throughout ninety percent of this novel. But when he describes Old Ben, he lays it all out there like granny’s jammies on the line. The thing is a monster: untrappable and invincible. It carries around countless bullets in its hide, one of its paws is mangled from a bear trap, and over the years it has killed countless dogs of the men who have attempted to bring it down in vain. It is, quite tritely, a symbol of nature: wild, free, invincible, untamable nature. Meanwhile, Man (or man), who is both puny and little in the same sentence, is anything but. To break it down for us, Faulkner offers this one-hundred-forty-three word decree:

It was as if the boy had already divined what his senses and intellect had not encompassed yet: that doomed wilderness whose edges were being constantly and punily gnawed at by men with plows and axes who feared it because it was wilderness, men myriad and nameless even to one another in the land where the old bear had earned a name, and through which ran not even a mortal beast but an anachronism indomitable and invincible out of an old dead time, a phantom, epitome and apotheosis of the old wild life which the little puny humans swarmed and hacked at in a fury of abhorrence and fear like pygmies about the ankles of a drowsing elephant; – the old bear, solitary, indomitable, and alone; widowered childless and absolved of mortality – old Priam reft of his old wife and outlived all his sons.

Sam Fathers is also one with nature, and can pretty much divine what the bear is up to at any point. He’s such a Jedi of the forest it makes you wonder why he can’t just lead the hunting party to Old Ben’s hidey-hole so they can surround the brute and light it up with rifle fire. For example, when Isaac is on his stand with his gun, keeping his eyes peeled for the bear, Sam appears out of nowhere and tells him that not only had the unseen bear been watching him, but he understood why the bear hadn’t gotten get any closer: “It’s the gun,” he says. “You will have to choose.” This means that the boy can only catch a glimpse of the primal beast unarmed. Later, when Isaac goes off alone to “hunt” the bear without a weapon, he learns that that bear still won’t let him see him because the boy is armed with a wristwatch and a compass. Despite being an expert woodsman at thirteen, he’s tainted by technology. Sam, the man who had taught Isaac how to hunt, and who anointed him with the blood of his first buck kill, dribbles out this ripe fortune-cookie gibberish:

Be scared. You cant help that. But don’t be afraid. Aint nothing in the woods going to hurt you if you dont corner it or it dont smell that you are afraid. A bear or a deer has got to be scared of a coward the same as a brave man has got to be.

From this point, the story almost writes itself. Isaac learns how to be one with nature from Sam, and then uses this wisdom to eventually get a glimpse of the great bear, become one with the universe, and trade his considerable inheritance for a childless, unproductive life and an allowance of fifty dollars a month.

Perhaps I’m not being entirely fair to Faulkner here. Faulkner knows hunting, and whenever he doesn’t get tangled up in his modernist pretensions, his detail of the woods and the animals in it can be quite evocative. So can his depictions of the hunting life. Perhaps if one views “The Bear” as a fantasy with Sam Fathers standing in for Gandalf the Grey (or Red, actually), some of Faulkner’s indulgences could be forgiven. Being the prime architect of the Southern Gothic genre, Faulkner also seems to have a real urge to tell stories through myth and to point to the future by reaching back into the past. This comes through despite the obvious shortcomings of Go Down, Moses, and has a way of sticking with a reader long after he turns the last page.

Boon Hogganbeck is also interesting. He’s a big, bearded white (perhaps known in Faulkner’s Mississippi milieu as a “cracker”) who can barely count to four and never found a bottle of whisky he couldn’t conquer. He can’t shoot straight and is perfectly useless as a hunter, yet the party keeps him around anyway. We wonder why until we find out: when Isaac, Sam, Boon and Lion finally track down Old Ben, the dog takes the beast by the throat, and Boon leaps on top of it and buries a blade beneath its shoulder, finally doing the monster in.

You could probably tell by now that I am not exactly a fan of William Faulkner, but the death of Old Ben proved to be some riveting literature. As an added bonus, Sam drops dead soon after. They’re both one with nature, you see, so it makes thematic sense that one cannot live without the other. And if you’re wondering about how to square Boon’s great act with Faulkner’s white guilt agenda, remember that Boon is one-quarter Indian and that Faulkner never tires of reminding his readers of this.

At this point, we are halfway through the story. Why call it “The Bear” when you kill the titular character and one of your main protagonists halfway through? I am not sure, but what I can do is summarize the remainder of the story in a few paragraphs: Isaac learns about his family’s sordid history, and is so disgusted he renounces his inheritance the moment he turns twenty-one. Then he defends his decision to his older second cousin, Carothers McCaslin “Cass” Edmonds, who stands to gain the inheritance if Isaac follows through with his plan. What Isaac learns, basically, is that Old Man Carothers had not only sired Tomey’s Turl with his slave Tomey, he had also sired Tomey with Tomey’s mother, another slave woman named Eunice, who committed suicide after giving birth to Tomey. Then, after he impregnated his own daughter, that daughter died giving birth to Tomey’s Turl, Lucas Beauchamp’s eventual father.

Talk about curses.

So with this grotesque and radically atypical scenario burning in our minds, Faulkner uses the sins of this “evil and unregenerate old man” as a springboard for a larger discussion of the how the South is cursed by God, how horrible slavery was, and how blacks are really equal or superior to whites – all couched in endless, disjointed sentences encumbered with whiny Christian theorizing (“. . . if He could see Father and Uncle Buddy in Grandfather He must have seen me too . . .”) and philosophical platitudes (“. . . no man is ever free and probably could not bear it if he were . . .”).

Here is a quick rundown of Isaac and Cass’s frank discussion on race, which is hard to read, both for its dense, fragmented prose and for the racial lies it conveys:

ISAAC: Blacks will outlast whites. He remembers how his grandfather impregnated Tomey and dismissed her because she belonged to an inferior race, but still bequeathed a thousand dollars to his inbred spawn. He did it reluctantly because blacks “are better than we are. Stronger than we are. Their vices are vices aped from white men or that white men and bondage have taught them: improvidence and intemperance and evasion – not laziness: evasion: of what white men had set them to . . .”

CASS: What about the blacks’ promiscuity, violence, lack of self-control, and “inability to distinguish between mine and thine . . .”?

ISAAC: “How distinguish, when for two hundred years mine did not even exist for them?”

Of course, this is nothing but a dodge – pure making excuses and question-begging. Isaac’s premise that blacks are equal to whites is the same as his conclusion, and his claim that the intervening two hundred years of slavery had disguised this does nothing to prove either. Well-meaning whites have been resorting to such circular reasoning when justifying pro-black and anti-white policies such as affirmative action for decades now. The “footrace metaphor” [2] is a great example.[1] [3] More recently, one James McWilliams, in his article “White Tribe Rising” in the 2018 edition of The Hedgehog Review, uses the Isaac McCaslin character as part of an argument against white people acting in their own racial interests.[2] [4]

So William Faulkner has influence far beyond his own time. In many places, Go Down, Moses is baffling and incomprehensible – but not baffling and incomprehensible enough, apparently. We should also note how Faulkner avoids addressing Cass’ claims of black promiscuity, a tacit admission that the older cousin is correct, at least on that count.

Faulkner also never considers how whites behaved as slaveowners as compared to non-whites. If slavery is a reason to curse an entire nation or people, then wouldn’t every nation and every people be cursed as well? Why only whites? Because whites were the worst slaveowners of them all? According to Thomas Nelson Page [5] who, unlike Faulkner, witnessed slavery firsthand, American whites actually made benevolent slave masters by the standards of the day. And according to historian Robert Davis, Muslims and Ottomans made especially reprehensible ones.[3] [6] Faulkner was an educated American who was born in the nineteenth century. He must have known about slavery in the Muslim world and in Africa, which was still extant in his lifetime. The “Great Forgetting” [7] hadn’t entirely happened yet, so why didn’t Faulkner execrate these parts of the world as much as he did Dixie? Why didn’t he also mention the well-known tendency of Indians to slaughter their enemies – men, women, and children – rather than enslave them? Other than Faulkner’s clear anti-white animus, there isn’t a satisfactory answer to any of these questions.[4] [8]

“Delta Autumn,” the book’s penultimate story, is in many ways a coda for “The Bear.” We’re back in the present day and Isaac is now the old man of the hunt, accompanying the sons and grandsons of the original hunters who knew Sam Fathers. Included in this group is a young Roth Edmonds, who seems to harbor a grudge against the old man. The way in which Faulkner reveals this grudge, however, only further sharpens the anti-white insult that Go Down, Moses really is. One morning, before the party takes off to hunt, Roth decides to let the old man sleep. After he wakes, Roth gives him an envelope stuffed with money and instructs him to give it to a young lady who will appear soon and to tell her, “No.”

This young lady is not only black, but Lucas Beauchamp’s grandniece. She is also carrying Roth’s child in a basket – a boy. Roth, feckless young man that he is, is now following in the footsteps of old Carothers as the black and white lines of the McCaslin family tree have finally been reunited. While this may make a grand narrative resolution, it strains credibility as it represents the fourth time in the novel that white men lust over black women (Roth’s father Zack had a similar regrettable episode in “The Fire and the Hearth” with Lucas’ wife Molly). It’s also the third instance of white-on-black incest. From this highly unlikely scenario, William Faulkner builds his great anti-white edifice.

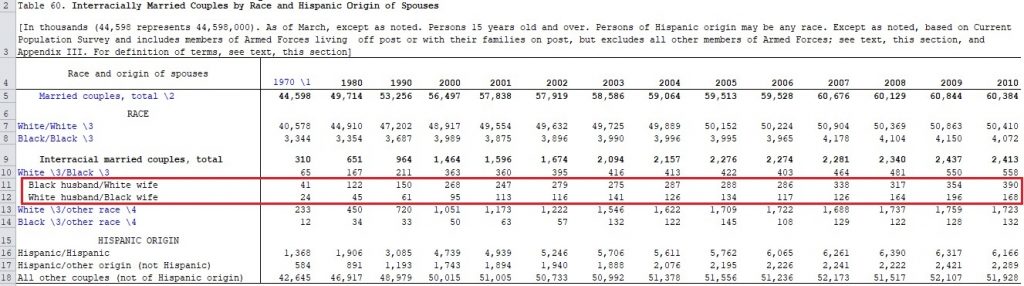

And highly unlikely it is. In the United States, black-white mixed marriages have always been more likely to have a black husband than a white one. In 2010, this was the case seventy percent [9] of the time, with 390,000 mixed marriages having a black husband and 168,000 having a white one.[5] [10] This extends beyond whites and blacks as well. According to Infogalactic [11]:

Among blacks, men are much more likely than women to marry someone of a different race. Fully a quarter of black men who got married in 2013 married someone who was not black. Only 12% of black women married outside of their race.

Faulkner is an odd bird, however. In some ways, he’s a superficial race realist. He’s not afraid to sprinkle the word “nigger” liberally into his prose, simply because that’s how people spoke in his day and prior. Further, in other contexts, he comes across as a red-pilled race realist. For example, in Absalom, Absalom he writes:

. . . Down there in the stable a hollow square of faces in the lantern light, the white faces on three sides, the black faces on the fourth, and in the center two of [Sutpen’s] wild negroes fighting, naked, fighting not as white men fight, with rules and weapons, but as negroes fight to hurt one another quick and bad.

Go Down, Moses has moments like this. If you leave out Faulkner’s egalitarian sermonizing, many of his scenarios do show blacks as brutish, irresponsible, and highly superstitious – that is, as not superior to whites in any way. “Pantaloon in Black” portrays a thuggish black with superhuman strength who murders a white when he cheats at cards, and then refuses to repent because he no longer believes in God. “Go Down, Moses,” the novel’s eponymous final story, features a black murderer who doesn’t even have such an ontological excuse – and the way in which his relations (including Molly Beauchamp) mourn his execution with delusory Christian chanting is typically, and quite unflatteringly, black. Tucked in “The Bear” is a chilling scene in which Isaac tracks down Fonsiba, one of Lucas’ sisters, to give her her inheritance. This is five months after a well-spoken, well-dressed black man appears before Cass to announce his intentions of eloping with her. He claims he can provide for Fonsiba, since he has inherited money from his ex-slave father who fought for the Union during the Civil War. When Isaac finally finds them, however, they are living in squalor under a burden of increasing debt. The man keeps telling Isaac that he has it under control, but that’s clearly a lie. When Isaac asks Fonsiba if she’s all right, she can only respond by saying, “I’m free.”

Finally, a word about Faulkner’s modernist style. Go Down, Moses is for the most part an excruciating book. Reading it takes work, requiring – at least for this reviewer – reading passages numerous times before gleaning their exoteric meaning (let alone any esoteric ones). And this is by design, as if Faulkner wished to make literature an exercise in hermeneutics rather than a storytelling art. His favorite word, it seems, is “he.” He employs it in almost every sentence in Go Down, Moses, but it is not always clear to whom “he” refers. Faulkner will refer to person X as “he” in one sentence; then, in the following sentence, person Y will say or do something to person Z. (It could be a flashback, or a flight of fancy – who knows?) Then there will be a semicolon or em-dash followed by a clause, the subject of which is predictably enough, “he.” So to whom does this second “he” refer? Well, one would have to reread the passage several times to figure that out – it could be person X, Y, or Z, depending on Faulkner’s mood, it seems. Basically, Faulkner, like other modernist writers, does not respect the reader’s time. He could have made his prose clearer, but didn’t. Instead, he arrogantly presumed that the payoff he was offering in Go Down, Moses would be worth the effort of reading the thing. It isn’t – except in this reviewer’s case, since I am sparing you the pain and reporting to you the truth about Go Down, Moses.

Please don’t read it, but understand it for what it is. Despite the familial vastness of its mythology and moments of sharp, authentic drama, it is and will always remain enemy literature.

Notes

[1] [12] From Douglas Detterman,“Tests, Affirmative Action in University Admissions, and the American Way,” in Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 2000, Vol. 6, No. 1, p. 45 [13]:

Members of minority and majority groups are pictured in a footrace. Because of past discrimination, the majority member is represented as having a head start. Affirmative action is seen as a way of correcting for the disadvantage of the minority member. The idea is that by giving advantage to the minority member in college admission, the difference in starting position will be remedied and eventually there will be no differences between minority and majority group.

[2] [14] Here is how James McWilliams uses Go Down, Moses to aid his anti-white theorizing in his Hedgehog Review article (and note that he uses Isaac’s nickname, Ike):

So Ike – to put it into terms of current identity politics – checks his privilege, not only for his peace of mind but for a larger cause he cannot fully articulate. More telling than Ike’s renunciation of his patrimony is his family’s enraged response. In their eyes he is shirking his heritage, selling out tradition and community for something he can’t explain . . .

Ike’s betrayal, and the anger it evokes, are instructive. By willingly ceding the inherited power of whiteness – what history bequeathed him – in the name of an abstraction (equality) without precedent in historical reality, much less in any community anyone has ever known, Ike represents the idealism articulated most convincingly by white reformers ranging from the antebellum abolitionists to the civil rights activists of the last century, all of whom were willing to exchange the privilege of inherited status for the dream of social equality. It is a dream that requires a leap of faith, one often made possible by education, idealism, religious conviction, or some kind of transformative experience.

McWilliams is correct on one account: It does require a leap of faith and religious conviction to insist that whites renounce their heritage and legacy the way Isaac McCaslin did. One would have to ignore an overwhelming amount of historical, psychometric, and scientific data about racial differences in order to do so.

[3] [15] In Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters (Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), p. 79, Robert Davis describes what it was like to be a white galley slave in the Ottoman Empire. I defy anyone to say that the life of the average Alabama field slave was any worse than this:

Galley slavery was, in all, an unspeakably wretched existence, made worse (if possible) by the unhappy awareness that the main task of a slave oarsman was essentially to work himself to death to help his masters seize more slaves like himself – an employment in which, as Mascarenhas lamented, “a man dies without acquiring any honor, in capturing Christians, his friends and relatives.”

[4] [16] I have never understood why Southern-apologist paleoconservative scholars like M. E. Bradford and Clyde Wilson eulogize Faulkner so. Wilson describes [17] Faulkner as “the greatest writer produced by the United States in the 20th century,” and Bradford opined positively on Faulkner here [18]. Why they never showed William Faulkner the same scorn he shows their beloved Southland is perhaps the only thing I find more baffling and incomprehensible than Go Down, Moses itself.

[5] [19] This is an image from the 2011 Census [9] showing the trends of black-white marriages in the United States since 1970 (click to enlarge). Note how the number of white-husband-black-wife unions has never come close to equaling the number of black-husband-white-wife unions.

Spencer J. Quinn is a frequent contributor to Counter-Currents and the author of the novel White Like You [21].