A Phone Call for Mayhem:

How JFK Caused the 1960s Race Riots

Posted By

Morris van de Camp

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

2,619 words

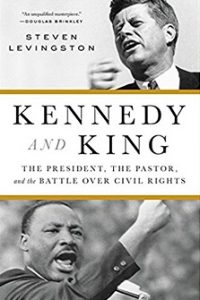

[1]Steven Levingston

[1]Steven Levingston

Kennedy and King: The President, the Pastor, and the Battle Over Civil Rights

New York: Hachette, 2017

To borrow from the wit of Edward Gibbon:

If a man were called to fix the period in the history of the world, during which the white race in North America was most foolish and short sighted regarding managing the non-white races in their midst, he would, without hesitation, name that which elapsed from the second term of Eisenhower to the accession of Nixon.

The man at the center of this span is President John Fitzgerald Kennedy (JFK). Kennedy was a wealthy son of privilege. His family played the “poor, oppressed Irish” bit to the hilt in their carefully marketed backstory,[1] [2] but the Kennedys were hardly socially alienated or oppressed. JFK’s grandfather Patrick Joseph Kennedy was one of the delegates at the Democratic Party Convention who nominated President Grover Cleveland in 1888, and JFK’s maternal grandfather was Boston Mayor and Massachusetts Congressman John Francis “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald. JFK grew up rubbing shoulders with Massachusetts’s WASP elite and attended elite schools.

JFK’s family was so rich that although Kennedy grew up in the 1930s, he didn’t know about the Great Depression until after he was taught about it in history class. As President, Kennedy surrounded himself with other Northeastern progressives. Many of them, like Sargent Shriver and Assistant Attorney General Nicholas de Belleville Katzenbach, were descended from prominent men in the American Revolution. All of them laid the foundations for an ongoing Negro revolution in the United States, as well as a black African/Third World capture of the Democratic Party as represented by the likes of the Somali Congresswoman Ilhan Omar.

The Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr. (good liberals always give the man the full title) was from a racial minority, but he was in the top social rung of that minority. His father was a minister in a large black church. King got a Ph.D. in theology at Boston University, although it has since come to light that his doctoral work was plagiarized. Like Kennedy, King was also not beaten down or oppressed, but supported throughout his career by highly talented, highly sympathetic whites and Jews who covered for any mistakes he made.

How and why JFK and his team got involved with King and the “Civil Rights” Movement deserves study from the perspective of a Rightist white advocate. One book that sheds light on the man and his time – or at least attempts to shed light – is Steven Levingston’s Kennedy and King.

Reading between the lines

This book is something of a puff piece supporting a liberal Jew’s view of the “Civil Rights” revolution. The first 70 or so pages of the book contains sticky-sweet phrases like, “King’s rise to stardom had seemed meteoric, but his path through the racial thicket of America, like that of many blacks, had been one of fear and anguish – navigated by courage.”[2] [3]

The thesis of the book is that King appealed – like Jiminy Cricket, but more Christ-like – to JFK’s conscience to get the various “Civil Rights” laws moving. Because of the artificial sweetener, this reviewer read the book from a detached, between-the-lines perspective. And the first thing that one sees is why Negro race riots and disorder began while Kennedy was president, progressively got worse, and then ended with Nixon’s election.

A single phone call by Kennedy set the fuse for a decade’s worth of black mayhem.

Before that call, though, one must look at the nature of the politics of the 1960 election. On the surface, the American political system was split at the time in a way that Oliver Cromwell and King Charles I would have understood. As a rule of thumb, the Republicans were Yankee Protestants in the North (Cromwell’s folks), and the Democrats were Southerners and Catholics, especially Irish Catholics (King Charles’ supporters). Black voters were usually Republicans, but the Roosevelt administration’s New Deal had peeled off many of them. In 1960, the black vote was up for grabs – and it mattered. If just enough blacks in the Northern cities went for Kennedy, states like Michigan or Illinois would flip into JFK’s column.

Levingston doesn’t go into the details of how the “Civil Rights” Movement developed prior to the 1960s. In fact, very few historians do. “Civil Rights” (i.e., black racial agitation) related to desegregation had become a serious movement by the early 1930s. King’s father had been involved in desegregation efforts as early as 1942. And newspapers carried opinion columns by the desegregationist activist and baseball star Jackie Robinson.

As a result of this activism and metapolitical efforts, “civil rights” became one of the main issues of the 1960 US Presidential Election, and Kinghad become one of the main leaders of the “Civil Rights” Movement after leading the Montgomery Bus Boycott in the mid-1950s. However, he failed to properly register his car with Georgia’s Department of Motor Vehicles, and was put on parole for the violation. After he was arrested while agitating, his parole was suspended and he was put in jail. The media went berserk, and the presidential candidates had to scramble for vote-getting and vote-keeping responses. The Nixon campaign didn’t comment on the situation at all. And after a series of angry arguments among his staff, Kennedy finally made a call to King’s wife, Coretta Scott King, expressing concern. The call was carefully calculated to appease blacks and liberals, but also not to enrage the South. It worked, but Kennedy then had a debt of sorts to King and his movement. Black agitators called in this semi-debt to the fullest. And later in the decade, entire cities would burn.

The “Freedom Riders” crisis (May 1961)

King and the other leads of the “Civil Rights” Movement realized they now had a lever that could move the White House during the “Freedom Riders” crisis of May 1961. A group of Jews and blacks (I believe most of the “whites” involved were, in fact, Jewish) rode on some chartered buses to desegregate bus stops in the Deep South.[3] [4] They wished to raise awareness of violations of Morgan v. Virginia and other court rulings, which ruled that bus stops couldn’t be segregated.[4] [5]

The Freedom Riders stunt got a great deal of media coverage. Angry Southerners attacked the Freedom Riders, and a bus was burned. For white advocates, it was bad optics. The Kennedy administration had to step away from dealing with the Cold War to consult with King and local officials to calm matters.

King’s antics in the smaller cities of the Deep South (June 1961-August 1962)

After the Freedom Riders stunt petered out, King continued agitating across the South. He and his followers would descend upon small cities in Georgia or elsewhere and create a crisis. The tricks they used were not all that different from those of the other Green Marchers [6] – which is to say, officially they were “non-violent,” but they would deliberately violate local laws, prompting a police and government response. The media would frame the affair as one of the police behaving badly. One of the tactics of these “non-violent” protesters was to get as many people arrested as possible to fill up the jails, causing a further crisis for the local government.

Whites reacted. Soon, there was a wave of Negro church burnings and other forms of white counter-agitation. Levingston doesn’t dive into the details of each individual church burning; many were undoubtedly insurance frauds or hate-hoaxes, but they did prompt much concern from the Kennedy administration. King:

. . . kept the pressure on the president. In a telegram to the White House, he raised the possibility of John Kennedy’s worst fear in the civil rights battle: blacks erupting into violence. Noting the attacks in the South, King said: “If Negroes are tempted to turn to retaliatory violence, we shall see a dark night of rioting all over the South.” King promised to discourage blacks from resorting to extreme measures, but he warned, “I fear my counsel will fall on deaf ears if the Federal Government does not take decisive action.”[5] [7]

This veiled threat should have been followed up with a public return telegram explaining that the President would arrest King for rebellion and subversion if rioting broke out, but Kennedy instead half-heartedly intervened in favor of the “Civil Rights” demonstrators through back-channel calls to mayors, state governors, sheriffs, and others. As a result, Kennedy ceded moral authority to the blacks.

To put it in terms Carl von Clausewitz would approve, race riots are an extension of politics through other means. After Kennedy made his call to Coretta Scott King, black agitators knew that if they wished to get something out of the White House, all they had to do was create, or threaten to create, a riot. As long as there was someone in the White House who owed – or thought he owed – blacks a political debt, the temptation was always there for more and more black rioting.

Desegregating Old Miss & Bull Connor at Birmingham (September 1962-April 1963)

As the Kennedy administration developed, King and the “Civil Rights” Movement continued to agitate. In September 1962, Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett and the Kennedy administration painted themselves into a corner over a black Air Force veteran[6] [8] who was seeking to attend the University of Mississippi. A deadly riot followed. The Kennedy administration was less than prepared for the disorder, and again had to disengage from serious Cold War problems to deal with the crisis. The Old Miss riot also demonstrated (again) that any violent flare-ups on the part of “civil rights” activists would result in Kennedy administration phone calls, and often US Army soldiers would end up becoming de facto supporters of the non-whites.

A short six months later, the “Civil Rights” Movement moved on to Birmingham, Alabama. The protestors complained that blacks could spend thousands of dollars in Birmingham’s high-end shops, but not eat at the shop’s restaurant. Birmingham businessmen were actually considering desegregation, but the situation quickly got out of hand because of the actions of two uncompromising men, Bull Connor, the white Commissioner of Public Safety, and the black activist Fred Shuttlesworth. Bull Connor enforced the segregation law, and Shuttlesworth carried out aggressive protests.

The optics in the Birmingham riot were pretty bad. Birmingham was enough of a fiasco that liberal white moderates issued a statement criticizing King. In response, King is purported to have written the now-famous Letter from Birmingham Jail [9]. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy was furious with the “civil rights” activists in that they refused to post bond while howling about still being in jail. They were following Gandhi’s tactics of not paying for bail and thus upping the tension all around.

The Birmingham riots were the climax of relations between Kennedy and King. After their initial failures, “civil rights” activists, mostly organized by Shuttlesworth, shifted tactics and began to use children in the desegregation marches. Photographs of cute Negro kids being blasted by firehoses and getting arrested prompted a national outcry. Finally, there were negotiations between the “civil rights” activists and Birmingham whites. The blacks finally agreed not to protest further, and the whites agreed to desegregate.

I could only read about this with sadness. Negotiating with activist sub-Saharans is different from France and Germany negotiating over treaties. In the latter sort of agreement, both sides reach an understanding, and civilization continues to function, and the people on one side of a line will get mail from the German postal service while the other side will get theirs from the French. But in the former sort of negotiation, whites give away their civilization wholesale. Whites retreated from Birmingham, and the town fell into African-style ruin [10].

Critical analysis

Ultimately, the definitive book on the “Civil Rights” Movement has yet to be written. Kennedy and King still looks at it in a utopian light. However, the entire history of “civil rights” as we know it today, including Kennedy and King, is little more sticky-sweet powder. This sugar-cloud creates a great historical misperception. Kennedy and King’s Epilogue offers as little insight into race relations or white resistance to “civil rights” as a nagging sermon by Rachel Maddow. In fact, the problems in the history of “civil rights” are multifaceted, including the following:

- Calling the social movement “civil rights” is a misnomer. The movement was a racial and ethnic conflict between whites on one side, and non-whites and Jews on the other. Furthermore, “rights” are actually established by the state and society. White societies bestow the rights – free assembly, the right to bear arms, free speech, freedom of religion, and so on – that whites are comfortable with. Black societies don’t create rights at all. If blacks can create a government, at best it will be ruled by an elite group plundering the government’s foreign aid account; at worst, it will be as lawless as Somalia.

- The timing and flow of the “Civil Rights” Movement is usually misinterpreted. Segregation was instituted by the generation that followed the Civil War nearly thirty years after the end of slavery. Desegregation began in the 1930s. Resistance to desegregation doesn’t really begin until the mid-1950s, and then only in those parts of the nation where there were, or are, large numbers of blacks in proportion to whites, and when children were involved.

- Kennedy and King doesn’t take the contemporary criticism of “civil rights” seriously. Southern governors were simply “virulent racists.” Nobody ever asks why they became “virulent racists.” While the low-IQ Congressman John Lewis is interviewed regarding his participation in the march to the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the white policemen and whites of Selma resisting the march aren’t interviewed.

- The results of the “civil rights” victories in places like Detroit and Selma aren’t looked at by any mainstream historians, even though they are apparent. Black rule turns cities to ruins.

- White resistors to “civil rights” should not be seen as “bigots” and “virulent racists,” but rather as people resisting domination by a different people. No historian simplifies the Irish troubles to a conflict between a group of “angels” fighting a group of “bigots.” Indeed, in light of the ever-expanding failed-state phenomenon in Africa, coupled with the return-to-prairie phenomenon in cities like Detroit or East St. Louis, one can see that they had a point.

- Blacks did not win the “civil rights” struggle. Whites fled “civil rights” and created suburbs.

Notes

[1] [11] Many American presidents carry on this “rise from poverty” charade. This includes William Henry Harrison. Harrison was born in Virginia to a prominent family, but played up the log cabin thing. Abraham Lincoln, while poor, was not from the lower classes, either. His grandfather had been a captain in the American Revolution. Lincoln was also descended from Hannah Salter, who was the daughter of Captain Richard Salter (1685-1730), a member of the Colonial New Jersey Assembly. Hannah was also the niece of colonial New Jersey’s Governor Andrew Browne (1638-1707). Lincoln only grew up poor because his grandfather died intestate; thus, under Virginia’s laws of primogeniture, his grandfather’s property went to his uncle, while his father got nothing.

[2] [12] Levingston, Kennedy and King, p. 35.

[3] [13] I’ve always wondered if the Freedom Rider blacks were carefully screened by the organizers of the stunt. The situation could have been a big fiasco if one of the blacks had raped a Jewish woman or committed some other crime.

[4] [14] I want to emphasize that Morgan v. Virginia was decided in 1946. This emphasizes the point that the “Civil Rights” Movement was really scoring victories already in the 1930s, but didn’t begin to encounter serious white resistance until after the 1957 Central High School fight.

[5] [15] Ibid., p. 259.

[6] [16] One of the problems of enlisting blacks in the military is that they become “saintly” veterans afterwards. Recruiting non-whites into the Armed Forces is one of the largest problems for white advocates seeking a white ethnostate.