Jobbik: A Brief History of a Political 180

Posted By Visegrád Post On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled [1]

[1]Gábor Vona, the former President of Jobbik, in 2015. Beginning in 2013, Jobbik began to soften its earlier militant image, in what was known in the Hungarian media as the “candy campaign.” These efforts to appear more centrist gradually altered the party’s rhetoric beyond recognition. Source: Facebook.

4,685 words

Czech version here [2]

Translated by Guillaume Durocher

Long considered the most radical parliamentary party in Europe, over the course of only a few years, Jobbik has morphed into a centrist and pro-European Union party, completely abandoning its former radical rhetoric opposing the EU, NATO, the LGBT movement, and gypsy crime. Today, in fact, Jobbik is trying to ally with the liberal and progressive Left in order to topple Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his party, Fidesz. Thus, this article is a brief history of a political 180.

Jobbik now openly demonstrates with Ferenc Gyurcsány’s liberal party, and has concluded its alliance with the liberal Left more broadly in an anti-Orbán common front.

Fidesz’s prophecy has thus been realized. For years (at least since 2016), Viktor Orbán, his party, and their supportive media had been predicting that the former radical nationalist party and the Hungarian Left have allied themselves in order to topple the government. Prior to the legislative elections of April 2018 [3], and despite numerous signs of a rapprochement [4], this was not yet entirely true. But since March 15, 2019, it is most definitely true.

Indeed, during the March 15 commemorations – a national holiday celebrating the anniversary of the beginning of the Hungarian revolution of 1848 against Habsburg domination – while Mr. Orbán was hosting Poland’s Prime Minister, Mateusz Morawiecki [5], the main opposition parties gathered their supporters to establish a great anti-Fidesz front.

For the first time, Jobbik has begun openly demonstrating with the DK (Demokratikus Koalíció, or Democratic Coalition, a party stemming from a 2011 split with the MSZP, the Hungarian socialist party), the party led by Ferenc Gyurcsány, who served as Prime Minister from 2004 until 2009, and who had long been one of Jobbik’s despised enemies. The DK was represented by Klára Dobrev, Mr. Gyurcsány’s wife and the head of the party list in the upcoming European parliamentary elections. Since the demonstrations of April 2018, following Fidesz’s latest electoral victory, Jobbik has frequently demonstrated with the DK, all the while denying the existence of any alliance.

Among the other organizations present, there was the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP), the liberal Green party Politics Can Be Different (LMP), Momentum (the Hungarian En Marche!), as well as the Mayor of Hódmezővásárhely, Péter Márki-Zay, who is not a member of any party, and who was among the first to openly call for a coalition ranging from the DK to Jobbik in order to defeat Orbán [6]. These political forces agreed to put a strategy of supporting common opposition (or “independent”) candidates in place during the upcoming Hungarian municipal elections of October 2019, with the goal of preventing victories by Fidesz candidates.

[7]

[7]The flags of Jobbik, Ferenc Gyurcsány’s DK, and the MSZP together in March 2019. Source: YouTube.

Before concluding their gathering to the tune of the EU anthem (see the end of this video [8]), the gathered demonstrators of the opposition, echoing the Twelve Points that were demanded by the revolutionaries of 1848 [9], declared their own twelve points [10] under the heading of, “What does the Hungarian nation want?” They are:

- Democracy and the rule of law

- Non-partisan media, and an end of public financing for propagandistic media

- Independent public prosecutors and courts

- A reasonable and legal use of public money, and holding corrupt public figures accountable

- Tax justice, with an end to excessive income inequalities

- Freedom and support for science, culture, and education, and quality education throughout the country

- Decent salaries and working conditions, and an expansion and enforcement of workers’ rights

- A great social consultation, also including professional organizations, interest groups, and civil society

- Access to quality healthcare for all

- Social security, housing for all, and a stable future

- Effective action against the climate crisis, the protection of our natural wealth, and the defense of our environment

- The defense of the values of our nation and the European Union!

There is nothing new in this attempt to unite the various factions of the Left-liberal opposition. This had already been tried during the 2014 legislative elections, without the LMP – and without any great electoral success, for that matter. But in 2014, there was no question of Jobbik ever joining such a coalition, given the absolute mutual rejection between the liberal Left and the far Right at the time. The question was again openly raised in 2018, but the time was not yet ripe. But henceforth, they are finally united in their efforts to overcome Orbán.

How was Jobbik able to undergo such a change? Let’s take a look at the political reversal of the decade.

A Radical Party Which Arose in the Troubled Autumn of 2006

Jobbik as a party was founded in 2003, coming out of a youth movement that was created in 1999. It tried to occupy the nationalist niche in the face of the other nationalist party, the declining MIÉP (Hungarian Justice and Life Party), that was led at the time by the playwright István Csurka.

Following rather modest first steps, Jobbik managed to take advantage of the dramatic events of the autumn of 2006, when a private speech by the Socialist Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány was leaked to the press, in which he revealed in particularly crude terms the lies he had told during his campaign in order to remain in office during the April 2006 elections.

There were several consequences stemming from this exceptional political scandal:

- Uncontrolled riots throughout autumn 2006 (we recall in particular the “stroll” taken by a T-34 tank [11], which had been surreptitiously commandeered by an anti-government protester during the October 23 commemorations for the 1956 revolution against the Soviets), which were brutally suppressed by the police, who often attacked peaceful protesters and even beat up Máriusz Révész, a Fidesz MP.

- The Left’s electoral collapse and the political death of the liberal party (SZDSZ, or Alliance of Free Democrats), which had been a major pole of Hungarian politics since the end of Communism and the regime change of 1990.

- The complete domination of Hungarian political life by Fidesz, which has won every vote since the local elections of October 2006.

- The emergence of radical nationalism on the electoral stage in Hungary.

In 2006, whereas Fidesz respected the rule of law and categorically refused any risky attempt to overthrow the government outside of the legal and democratic framework, radical nationalism prospered among those who wanted Gyurcsány to be thrown out of office immediately. During the subsequent years, Gyurcsány as a personality became something of a punching bag for a population exasperated by the government and which was being victimized by the severity of the economic crisis – first in 2006 in Hungary, and then worldwide in 2008, which forced the country to accept a financial bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Union, and the World Bank. At the time, Jobbik’s leaflets explicitly called for Gyurcsány to be put in jail.

As a young party, Jobbik managed to thrive in this atmosphere of cold civil war and achieved a great political victory with the creation of an (unarmed) civil militia in 2007: the Hungarian Guard.

Under the leadership of its young President, Gábor Vona, Jobbik took off in the 2009 European elections by winning fifteen percent of the vote, and then seventeen percent in the 2010 parliamentary elections, when Fidesz handily won with more than fifty percent, securing a two-thirds supermajority in Parliament, which gave them the ability to make changes to the Constitution without having to consult the other parties. Until the rise of Golden Dawn in Greece, Jobbik was considered the most radical Right-wing party that had attained parliamentary representation in Europe. Jobbik made national and international waves several times, notably when it sent the Hungarian Guard to march in villages against what they called “gypsy criminality.”

[13]

[13]Gábor Vona famously took his first oath of office as an MP in 2010 wearing his Hungarian Guard uniform – in stark contrast to how he would present himself only a few years later (see above). Source: Jobbik.

Although it was their critical statements about certain Jews that caused the biggest scandals. In particular, MP Márton Gyöngyösi sparked a worldwide scandal and made a great impression as a result of comments he delivered in Parliament in November 2012 [14]. During a one-minute statement in which he mentioned the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the situation in the Gaza Strip, Gyöngyösi concluded by saying, “In the Parliament and in the Hungarian government, how many people of Jewish origin are there who pose a risk to Hungary’s national security?”

The outcry was immediate. The statement was condemned by all the other Hungarian political parties, and a demonstration even took place uniting Fidesz officials with those of the liberal Left. And at the end of 2012, the Simon Wiesenthal Center classified Gyöngyösi among the ten leading anti-Semitic figures in the world.

Jobbik also surprised observers through its international orientation, which was turned exclusively towards the East. Besides calling for Hungary to withdraw from the EU (whose flag Jobbik burned during a demonstration in January 2012) and NATO, Jobbik also wanted stronger ties not only with Russia, but also with Turkey, the Turanic world, and the Muslim world.

During the demonstration in which Jobbik burned the European Union’s flag, one of their slogans was one that had originally been used in the “no” campaign in Hungary’s 2003 membership referendum: “Shall we be members [of the EU] or free?”

The Onset of Detoxification (2013)

While Jobbik made a splash through its scandalous statements, between 2010 and 2014, Viktor Orbán’s government successfully reduced the public deficit, repaid in advance the IMF loan taken by the previous government, put a new Hungarian Constitution in place, and began its ongoing struggle with Brussels. And Orbán’s popularity has remained intact since his triumphant reelection in 2010.

Dealing with a political radicalism which had its limits, and that led them to run up against an electoral glass ceiling, Gábor Vona attempted to achieve his party’s “detoxification.” This strategic U-turn is known in Hungarian as néppártosodás. This term, which is not easy to translate, brings to mind something like the transition towards a “people’s party.”

At the end of 2013, Gábor Vona explained that Jobbik had always had two faces [15]: the radical face and a mainstream one, the latter embodied by more conventional people, and he said that it was perhaps a mistake to have only put forward the radical face of the party up to that time. He nonetheless added that these two “faces” had always coexisted and continued to do so, in harmony. He also added that this new communications campaign would not change the fundamental points of Jobbik’s program: to return Hungary to the Hungarians, to solve the problem of the coexistence of Hungarians and gypsies, and to refuse to accept Hungary’s domination by the European Union.

This video clip, from October 2013, broke with Jobbik’s previous communications strategy and image. The slogan asserts that Jobbik is “already the most popular [party] among the youth.”

This detoxification, inspired by those of other populist parties in Western Europe, had to deal with an important obstacle: the lack of changeover in the party’s management, meaning that the attempted shift was not very credible (unlike, for example, the Front National in France, whose detoxification was personified by Marine Le Pen’s assuming the party leadership).

In the 2014 elections, the results were more or less the same as in 2010 [16]: Fidesz kept its supermajority of two-thirds of the Parliament, while Jobbik made slight gains, winning twenty percent of the vote – lagging behind, however, the Left-wing coalition, which received twenty-five percent of the votes. Jobbik became the single largest opposition party, however.

2015 was the year of great changes. It began with a dispute between Viktor Orbán and Lajos Simicska, a businessman and media mogul who had until then been very close to the Prime Minister. Simicska, normally a very discrete person, publicly insulted Orbán and unceremoniously purged all his media of people favorable to the government. (Curiously, neither this nor the sight of journalists being immediately fired without cause stoked any indignation among liberals, either at home or abroad.)

2015 continued as a difficult year for Fidesz with the loss of two by-elections, which caused it to lose its constitutional supermajority. One of the two constituencies (half of Hungarian MPs are elected by proportional representation and half by one-round, first-past-the-post constituency elections) was won by Jobbik in a close result [17] (thirty-five to thirty-four percent). Given Fidesz’s difficulties, the opposition parties, including Jobbik, began to develop great hopes for 2018.

The migrant crisis upended the situation. In 2015, more than four hundred thousand migrants illegally crossed the Serbian-Hungarian border, which is along the Balkan route that leads to western Europe.

[18]

[18]For several months, Keleti Station in Budapest was an open-air migrant camp. Photo: TV Libertés.

The migratory chaos that wracked Hungary throughout 2015 contributed to Fidesz’s fall in the opinion polls, while Jobbik’s shot up to nearly thirty percent support. This, along with the two by-elections lost by Fidesz earlier in the year, led to great hope among Jobbik’s ranks. But they could not have anticipated Orbán’s coming response.

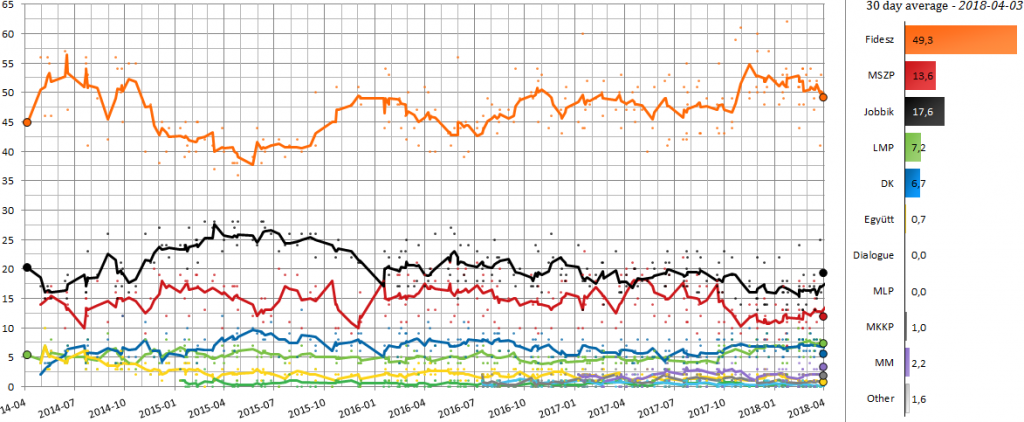

[19]

[19]Evolution of the popularity of the various Hungarian political parties during the April 2014-April 2018 legislature, according to opinion polls. Fidesz is in orange, MSZP in red, Jobbik in black, LMP in green, and DK in blue. In mid-2014, Fidesz experienced a lull in support, while Jobbik rose – but then the trends were reversed.

Contrary to the other transit countries, Orbán did not organize a “taxi” service for migrants to get from the Serbo-Hungarian border to the Austro-Hungarian one. Instead, he respected the European Union’s Treaty of Schengen (according to which Schengen border states must protect Schengen’s external border) and chose a frontal strategy [20]. He erected a fence along the Serbo-Hungarian border to block the migrants’ passage, which was completed in September 2015.

Concerned about this migrant flow and by the EU’s wish to impose a quota for the redistribution of migrants on all Member States, forcing all nations to accept them, the Hungarians massively supported their Prime Minister’s policy of securing the border and opposing Brussels’ quotas. The Left-wing opposition sided with the proponents of immigration, while Jobbik was put in an impasse by the hardening of Fidesz’s discourse, which also began to denounce George Soros’ networks [21]. Jobbik backed Fidesz’s position regarding the migrants, since doing otherwise would have alienated their existing base – but this allowed Fidesz to win back the momentum.

Orbán continuously pursued his campaign against mass immigration and organized a referendum in October 2016 [22] in which Hungarians were asked to accept or reject the EU’s migrant quotas. Under Hungarian law, a referendum must achieve a quorum of fifty percent in order to be valid. This threshold was not reached [23], but participation was nonetheless fairly good – forty-three percent – given that the Left had called for a boycott. The result: 98.36 percent of electors voted against Brussels’ mandatory migrant quotas [24].

During the campaign, Fidesz and Jobbik (as well as the Communist party, the Munkáspárt [Worker’s Party], which is not represented in Parliament) called on voters to participate and vote “no.” Most Left-wing opposition parties called for the vote to be boycotted so that the quorum would not be reached.

Jobbik constantly repeated throughout the referendum campaign that the government ought to resign in the event that the fifty percent quorum was not reached. Prior to the referendum campaign, Jobbik had proposed to Parliament a constitutional reform which would make it illegal for foreign powers to settle populations in Hungary without the approval of the Hungarian authorities. This proposal was rejected by Fidesz, which preferred its own referendum strategy. From its point of view, the referendum had the twofold advantage of consolidating its position in Hungarian public opinion as well as being a democratic argument it could use in the struggle against Brussels.

Jobbik’s only really active participation in the referendum campaign was a video clip featuring László Toroczkai [25], who was (and is) the Mayor of Ásotthalom, a village along the Serbian border, who had become famous for his social media campaigns against illegal immigration [26], and who had joined Jobbik’s leadership in 2016, becoming one of its Vice Presidents.

However, despite this video, Jobbik’s almost daily repetition of their call for the government to resign in the event of the referendum’s failure leads one to think that perhaps that is what Jobbik really wanted. At that time, the conflict between Fidesz and Jobbik had already intensified, as the oligarch Simicska had thrown his support and considerable media resources behind Jobbik.

At the same time, internal changes occurred within Jobbik during 2016 with the departure of one of its Vice Presidents, Előd Novák, an anti-Zionist and anti-EU figure. He was fairly hostile to Gábor Vona’s strategy of néppártosodás, and his reelection was vetoed by Vona despite the fact that he had won the vote among the party’s members. Shortly after, he was invited by the Jobbik parliamentary group to resign – which he did – and was removed from all his offices. László Toroczkai’s joining counterbalanced this departure and enabled them to try to counteract Orbán’s advantage in this area, since he had already made immigration the major theme of his social media campaigns. Thus, the appointment of Toroczkai [27], a respected radical nationalist and the founder of several militant nationalist organizations in his own right, allowed Jobbik to reassure its nationalist base amidst its change of direction.

Novák’s elimination also removed an internal problem, however, allowing the party to adopt a strategy going well beyond mere detoxification.

Anti-Orbánism at Any Cost

With Orbán having “shifted right,” Jobbik then tried to outflank him on the left by launching outrageous propaganda campaigns against both the Prime Minister and Fidesz more generally.

Following the referendum on migrant quotas in October 2016, Orbán submitted a constitutional reform on the subject to make it illegal for foreign powers to settle populations in Hungary without official authorization. He no longer had the supermajority to pass this without the support of any of the other parties; thus, the support of Jobbik MPs was essential, and put Fidesz in a delicate position. As the French magazine Causeur observed [28], “Orbán, a political animal, is forcing Jobbik to make a Cornelian choice: to either take his side or that of the ‘foreign party.’”

Gábor Vona then took a chance: He accused the Hungarian government of having established a legal immigration pathway through the sale of Hungarian treasury bonds (in Hungarian: Letelepedési Magyar Államkötvény), which allowed rich foreign investors to obtain a Schengen visa in exchange for the purchase of these bonds. He declared that Jobbik MPs would vote for the constitutional reform proposed by Fidesz only if this system of visa distribution were suspended. But Orbán did not yield to Jobbik’s blackmail. Jobbik, true to their word, did not vote in favor of the reform, which was then rejected by Parliament, given that it lacked the qualified two-thirds majority. The foreign press saw this as another affront against Orbán [29], one month after the referendum’s lukewarm success.

In fact, in doing this, Orbán managed to establish himself in the eyes of public opinion as the only resistance to illegal mass immigration, thus casting all the opposition parties in the role of the supporters of mass immigration, including Jobbik.

[30]

[30]Fidesz campaign poster that appeared all over Hungary just before the 2018 election, showing the major opposition figures with George Soros. The caption reads, “They want to break the border.” Source: anonymous.

From then on, total war was declared between Fidesz and Jobbik. Jobbik had wanted its position on migration to be subtle, and it was swept away by the public relations steamroller of Fidesz and its satellite organizations. Their accusation was hammered home: Jobbik had become a partner of the liberal Left.

Jobbik, however, gained one advantage: all the while pretending to cling to its anti-immigration rhetoric, it tried to appear in the eyes of the liberal opposition as Orbán’s most determined opponent, and the only party with a realistic chance of unseating him in 2018. What’s more, with the help of Lajos Simicska’s billboard ads, which appeared on nearly every kiosk and billboard across the country, they launched “anti-corruption” campaigns against Fidesz, plastering Hungary with signs accusing Orbán of being a crook. The exchanges between Vona and Orbán in Parliament also became particularly virulent during this period.

A Jobbik campaign ad in which Orbán is put in prison by Gábor Vona

In international affairs, also, it was time for Jobbik’s great shift toward the center. In 2016, the party no longer spoke of withdrawal from the European Union [31] (whose flag they had been burning a mere four years before), but rather simply called for EU reforms.

Similarly, Márton Gyöngyösi, who had been known up to that time for his hard-line anti-Atlanticism and his Eastern orientation, went so far as to claim in an interview with the Courrier d’Europe centrale in March 2018 [32] that “it doesn’t matter where you go, all the nationalists, extremists, and pro-Russians in Europe hail Viktor Orbán and consider him an example.” He also explained in this interview that it was not Jobbik which represented a threat to democracy, but Viktor Orbán’s government.

Jobbik had also been well-known for its Turanism, or the belief that Hungarians bear close cultural and ethnic connections with Turkic peoples, and its passion for Turkey more generally. While these were never explicitly renounced, they were gradually put to the side. Likewise, Jobbik’s previous critical stance toward Zionism and certain Jews was dropped; this was highlighted when, in November 2016, Vona gave an address at the Spinoza Theater in Budapest, a well-known meeting place for Jewish intellectuals, and when he sent Hanukkah greetings to Hungary’s Jewish leaders [33] the following month (they were rejected). A year later, Vona publicly denounced his party’s earlier critical remarks about certain Jews [34].

On social issues, too, Jobbik shifted direction:

- Contrary to its previous position, Jobbik said it no longer wished to ban the Gay Pride parade in Budapest, on the grounds that it formed part of the defense of public freedoms which had supposedly been greatly reduced under Viktor Orbán’s government.

- Jobbik began supporting Left-liberal MPs in their appeal to the Constitutional Court to oppose the law concerning Central European University (CEU) [35], which is financed by George Soros. The goal of this law was to force CEU to adhere to the same rules that apply to other universities in Hungary [36], and to not have the ability to grant foreign diplomas without also offering classes in the foreign country in question (in this case, the United States).

- In an interview given in March 2018 on local television and published in the liberal opposition weekly HVG [37], Jobbik MP and spokesman Ádám Mirkóczki went so far as to claim that Jobbik’s rhetoric prior to 2010 had not been genuine and had not reflected the party’s reality. He even added that Orbán had made Jobbik into the party that is most concerned with democracy, and that he ought to be thanked for this. László Toroczkai would publish a laconic response to this on his Facebook page: “It is not in my name that Ádám Mirkóczki has stated that the rhetoric prior to 2010 was not genuine.”

This strategy of Jobbik’s, which was publicly criticized within the party only by László Toroczkai, does not seem to have borne fruit in public opinion, where the polls indicated that Jobbik remained at its usual low-water mark of fifteen to twenty percent.

An unexpected event again stoked some hope among the opposition: On February 25, 2018 – six weeks before the parliamentary elections in April 2018 [4] – there was a municipal by-election in Hódmezővásárhely, in which Péter Márki-Zay, an unaffiliated candidate describing himself as a conservative who was disappointed in Fidesz, received the support of all the opposition parties, ranging from DK to Jobbik. He won this municipal election with fifty-seven percent of the votes, as against forty-one percent for the Fidesz candidate. This surprise win suggested that if there were a coalition of the entire opposition in individual parliamentary constituencies, then it would be possible to defeat Fidesz.

But the time was not yet ripe for that in 2018, and Jobbik refused to withdraw a single one of its candidates from the country’s 106 constituencies, all the while inviting liberal voters to vote for the Jobbik candidate when he seemed to have the better chance of beating the Fidesz candidate (particularly in the countryside, given that Jobbik is weakest in Budapest). Jobbik went on to say that it was ready to form a coalition after the elections with the liberal Green party, the LMP, as well as with the young liberals of Momentum, but rejected any cooperation with the MSZP or Gyurcsány’s DK.

However, to the surprise of many observers, the 2018 parliamentary elections again gave Fidesz a two-thirds supermajority [38]. As for Jobbik, it peaked at nineteen percent – which was in second position, but still far behind Fidesz’s forty-nine percent. As for the “tactical voting” strategy, this was also a failure for Jobbik, which won only one constituency out of 106.

A Split Allowed Jobbik to Finally Opt for an Anti-Orbán Common Front

Gábor Vona had promised that, in the event of another electoral defeat, he would withdraw from Jobbik’s leadership, and he remained true to his word. He also resigned from parliamentary office and became a vlogger [39], continuing to promote dialogue and ties between all the members of the opposition with the goal of toppling Fidesz and Viktor Orbán.

In the aftermath, two candidates fought for Vona’s position: Tamás Sneider and László Toroczkai. Both have a radical past: Sneider is known to have been a skinhead leader in the 1990s, whereas Toroczkai had been a leader of the nationalist riots of autumn 2006. Each candidate shared a ticket with another candidate who would then become the party’s second-in-command: Tamás Sneider was joined by Márton Gyöngyösi, while László Toroczkai had Dóra Dúró as his partner – a Jobbik MP and Előd Novák’s wife.

Jobbik’s congress vote was close. The Jobbik cadres (notably Gábor Vona and Secretary General Gábor Szabó) largely supported Sneider’s candidacy, who won by a small margin. Toroczkai denounced the congress’ proceedings, saying that he had been allowed less speaking time. Sneider, despite his extremist past, pushed for continuing Gábor Vona’s strategy, while László Toroczkai categorically rejected any alliances with the liberal Left.

This situation led Toroczkai to create a group within Jobbik for mayors which would call for the adoption of a program that would return Jobbik to its Right-wing roots – an initiative that was rejected by the party’s leadership. Toroczkai was then dismissed from Jobbik, and soon after created his own party: Mi Hazánk Mozgalom (Our Fatherland Movement) [40]. He was joined by four Jobbik MPs and will lead a list in the May 2019 European elections.

Following these departures, Jobbik was now free internally to pursue anti-Orbánism to its logical conclusion. In the upcoming European elections, for example, Jobbik declared that one of the issues at stake is preventing Viktor Orbán from withdrawing Hungary from the European Union. This list will be led by Márton Gyöngyösi. The opposition parties did not want to put in place a common list against Fidesz, because of the proportional representation system. However, they plan to do so during the upcoming Hungarian local elections in October 2019.

With Jobbik’s participation in public demonstrations with its former foes on the liberal Left in March of this year, as discussed at the beginning of this article, there is no longer any doubt concerning what sort of strategies Jobbik is pursuing these days – unlike in 2018, when things were still relatively ambiguous. Likewise, the liberal Left has been signaling that it is willing to forgive Jobbik for its earlier stances in order to work with them, such as in February, when Gergely Karácsony, a liberal socialist who is running for Mayor of Budapest, and who had denounced Jobbik during the 2018 campaign for being “full of Nazis,” publicly defended Márton Gyöngyösi’s controversial 2012 statements about Jews serving in government [41]. Thus, Jobbik’s result in the European elections will give a first indication of how successful its common front with the liberal Left will be, given that it has broken with the party’s historic fundamentals.

This article is reprinted from the Visegrád Post [42], a site specializing in news from Central Europe from a Rightist perspective.