Hope for a Non-White Savior

Posted By Robert Hampton On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,072 words

Some on the Dissident Right hope that the next Pope will be black.

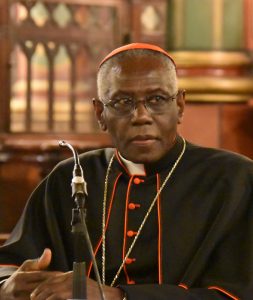

Guinean Cardinal Robert Sarah has distinguished himself from the open borders crowd that controls the Vatican. In a March interview, Cardinal Sarah said [2]:

The Church cannot cooperate with this new form of slavery that mass migration has become. If the West continues down this disastrous road, there is a great danger that, for a lack of a replacement birth rate, Europe could disappear, invaded by foreigners, as Rome was invaded by the barbarians. I speak as an African. My country has a Muslim majority. I think I know what I am talking about. . . . It is better to help people to flourish in their culture than to encourage them to come to a Europe that is completely decadent. It is false exegesis to use the Word of God to improve the image of migration.

He also said Islam would take over the world if Europe dies. The Cardinal did not apologize for these comments, and echoed them again in a May speech. Sarah is likewise a traditionalist who values the Latin mass and does not shy away from the Church’s politically incorrect teachings. He derides gender ideology [3] as “Luciferian,” and calls for Europeans to return to the true faith.

Trads and a significant number of identitarians hope he succeeds Francis and returns the Church to its full glory. However, it’s unlikely that a college of cardinals filled with liberals and Francis allies will select Sarah. The desire to see him become Pope reflects the peculiarities of conservative Christians. Many conservative Christians see the Third World – not the West – as the faith’s great hope. In their view, the West is too degenerate to save itself, and it must rely on non-whites for renewal. Even though Sarah opposes mass immigration, many conservative Christians celebrate it, because it delivers devout Christians to the godforsaken West.

This position is deeply anti-identitarian. Sarah’s papal elevation – or any other non-white’s elevation – would be an admission that the Church is no longer a Western faith. While Sarah is a traditionalist who values Europe, he’s an outlier. Third World Christianity is radically different from the white man’s faith. It’s influenced by native traditions, and encourages animosity toward Westerners. It would announce that “Africa is the faith” and that it will impose its ways on the West. Third World Christians tend to be more socially conservative than their Western peers, to be sure, but our civilizational struggle is not over abortion. It’s over our people’s survival.

[4]Historian Philip Jenkins’ The Next Christendom: The Rise of Global Christianity provides an in-depth picture of Third World Christianity. It does not resemble the Tridentine Catholicism of Cardinal Sarah. Throughout Latin America, Africa, and Asia, locals mix Christianity with their own native traditions to create a faith to which they can relate. They incorporate native dances and rituals – in some cases, including animal sacrifice – into their Christianity. Traditional Western religion simply doesn’t move them. Africans and Latin Americans are also obsessed with demons and witchcraft, and expend much energy on countering them.

[4]Historian Philip Jenkins’ The Next Christendom: The Rise of Global Christianity provides an in-depth picture of Third World Christianity. It does not resemble the Tridentine Catholicism of Cardinal Sarah. Throughout Latin America, Africa, and Asia, locals mix Christianity with their own native traditions to create a faith to which they can relate. They incorporate native dances and rituals – in some cases, including animal sacrifice – into their Christianity. Traditional Western religion simply doesn’t move them. Africans and Latin Americans are also obsessed with demons and witchcraft, and expend much energy on countering them.

Jenkins convincingly lays out the case that the Church’s future lies with the Global South: “There can be no doubt that the emerging Christian world will be anchored in the Southern continents.” Demographic trends show that non-white Christians will vastly outnumber white followers of Christ by mid-century. Meanwhile, Christianity is minimized in the secular West and faith is now relegated to “a personal matter.” Western society does not care about what religion you practice, insisting that church and state must remain separate. In contrast, the faith wields tremendous influence over the Global South and even inspires violent conflicts.

“Christianity has never been synonymous with either Europe or the West,” Jenkins argues, claiming that the faith was stronger in Africa and Asia for its first thousand years. According to the author, Europe only became Christianity’s heartland after 1400. This is a surprising claim from someone who has written for paleoconservative publications. Jenkins makes this argument to counter assumptions that Christianity is a “White or Western ideology foisted on the rest of an unwilling globe.” He makes a persuasive case that Christianity was strong in the Middle East and North Africa, but that the emerging Christianity is emanating out of sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America – two places where the faith was brought by Europeans.

Regardless, Jenkins does offer a corrective to those who claim Christianity is a white folk religion. While Europeans have been Christian for several centuries, it was never exclusively ours. Most readers understand that Christianity was formed in the Middle East and that its heart resided there until the rise of Islam. The Christianity we know in the West today was designed to accommodate the spirit and traditions of Europe. Jenkins notes that Gothic architecture felt alien to Third Worlders who had never seen the brooding forests of Europe. He argues that Gothic cathedrals aren’t a type of “Christian architecture,” but are rather European. This point should not be lost on those who argue that Notre Dame and other architectural wonders are exclusively Christian.

Cardinal Sarah is different from his African compatriots in that he upholds the Catholicism of the Gothic cathedrals and Latin ceremonies. The vast majority of Africans prefer a religion that speaks to them. Jenkins provides numerous examples of syncretism in African Christianity. Here you can find Church-sanctioned polygamy, animal sacrifice, and tribal dancing. Many Africans and other Third Worlders belong to independent churches that have dispensed with any connection to Western Christianity. Their Christianity more closely resembles the animism they supposedly left behind, simply with the addition of Christ-worship. These independent pastors often boast of their magical healing powers and ability to combat witchcraft. Many of these churches even promote African racial identity, and see themselves as superior to the colonizers’ faith.

The established churches also exhibit syncretism. In 2000, a Catholic archbishop in South Africa suggested it would be appropriate to include animal sacrifice in the mass. He said that this would be “a step towards meaningful inculturation.” Other bishops and priests have married – some to multiple wives. The churches in Africa also make use of tribal dancing during mass and promote imagery far removed from Gothic art.

Pentecostalism, too, is becoming popular in both Africa and Latin America, and is growing fast. This religious practice emphasizes personal spiritual revelation and ultimate scriptural authority. Snake-handling and speaking in tongues are common Pentecostal practices. In 2005, there were seventy-five million Pentecostals [5] in once-Catholic Latin America, and over one hundred million in Africa [6]. Those numbers have continued to grow since then. Pentecostalism challenges the Catholic establishment in Latin America and has attracted millions of former Catholics. The Church has responded by adopting evangelical practices to retain its flocks. And unlike other variants of Third World Christianity, Pentecostalism teaches submission to government authorities. Its spread in Latin America was encouraged by the CIA to combat Liberation Theology and other politically radical variants of Christianity.

A common meme among American conservatives is that Hispanics are traditional and devout Catholics. Jenkins dispels that notion with his evaluation of the popularity of evangelical Christianity, Liberation Theology, and syncretic practice in Latin America. Outside of Pentecostalism, most forms of Christianity in the region have not been conservative. Several bishops have in fact opposed Right-wing movements and leaders, and many religious leaders and figures have supported Communism and radical social reforms. The Church has tried to impose conservative bishops on Hispanics with mixed results. When this happens, too many leave the Church in favor of evangelicalism or quasi-pagan practices like Santa Muerte.

Throughout the book, Jenkins positively compares the global South to the secular North. The historian hopes that the South will evangelize the North and revive conservative Christianity. He retells a portion of Evelyn Waugh’s short story “Out of Depth,” which depicts a future England where bewildered whites listen to their black priest recite the liturgy in Latin. Many Westerners experience this already – just without the Latin. A black priest is more likely to employ bongo drums.

Jenkins sees mass immigration as a golden opportunity for evangelization. He critically mentions Jean Raspail’s Camp of the Saints for its depiction of this movement as an invasion. The author claims that most religious conservatives look fondly on the “browning” of Christianity. “They almost seem to be awaiting a benevolent Camp of the Saints scenario, in which quite genuine saints from Africa or Asia would pour north, not seeking racial revenge, but rather trying to reestablish a proper moral order,” he writes of conservative fantasies.

Anyone who has seen the behavior of migrants in Europe knows the new arrivals are not saints. They’re not trying to reestablish a proper moral order; they’re exploiting white generosity to impose their will on us. Still, some Christian conservatives retain their deluded view of the Third World because non-white congregations are often the only bulwark against progressive Christianity. Bishops from the global South have resolutely opposed gay marriage and rapprochement with the gay community. Jenkins in fact credits Catholicism’s shift to the South as the reason why the Church has remained conservative in comparison to other denominations.

Africans and other Third Worlders have had the same effect in other churches. Jenkins declares the twentieth century to be the last one in which whites ruled the Catholic Church: “Europe is simply not The Church: Latin America may be.” He argues that the Church now represents the interests of its Third World congregants, which partially explains why the Vatican is so pro-immigration. It wants non-whites in the West to fill up the pews on Sundays. The author goes on to detail non-white missionary efforts in the West, and describes how whites “need reconverting.” Jenkins is not so optimistic that whites will join churches where they’re alone amid “a sea of black faces.”

He says in the book’s first chapter that a white Christian soon “may sound like a curious oxymoron, as mildly surprising as ‘a Swedish Buddhist.’” The Next Christendom makes a convincing case for that impression. If the Christianity of tomorrow will be a primitive Third World death cult, whites will become even more alienated from it. It will not connect with their souls and will demand that they reject science and reason in favor of witch-hunts and shamanistic healing.

No identitiarian should want whites to become snake-handlers for Christ.

Many on the Dissident Right argue that whites need a spiritual renewal to save ourselves, saying we cannot restore the West without God. A concrete vision of how that would actually come about is rarely offered, outside of the Church holding a Third Vatican Council that would bring back the Latin mass and call for a new crusade.

The chances of that happening are essentially nil, but the hopes for the based black Pope persist. Nevertheless, Cardinal Sarah will likely not be the next Pope. Church politics and his traditionalist reputation preclude that. Even if he does become the new Vicar of Christ, his faith will not bring Europeans back to the pews. His faith is not representative of the global South.

Third World Christianity is not the West’s salvation. It’s a direct threat to us. Jean Raspail understood this in Camp of the Saints. A Christianity that sees non-whites and their folkways as its primary base will work to destroy the West and redistribute its riches to the entire globe. In this view, mass immigration is positive because it swamps the decadent West with (allegedly) faithful Christians. Its supporters might even describe that as divine punishment for whites. Third World Christianity’s social conservatism is not enough to mitigate this, either, given that it encourages Third World birthrates to skyrocket as it condemns birth control and contraception as the devil’s tools.

Everyone knows the West is decadent. That doesn’t mean that we need to import millions of non-whites as a punishment for our decadence. Rather than getting us to go to church and end pride parades, the new arrivals will simply overwhelm us and turn us into second-class citizens. We will become the Third World, and whites will sit at the bottom of the totem pole (around which African tribal dances will be taking place, presumably).

White renewal can only come from us – not from a based black Pope, not from anti-gay Pentecostalists, and certainly not from the Lord’s Resistance Army. Our fight is not about social conservatism or liturgy. It’s about our people’s survival. Third World Christianity threatens that.