Leni Riefenstahl in Modern Memory

Posted By P. J. Collins On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledOne of the delights of revisiting old movies after many years is finding out that you completely misread or misremembered certain scenes. Early on in the first part of Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia, we have the entry parades of the national teams. When the French team come by, they drag their flag in the dust – because, or so I assumed decades ago, these robust athletes were utterly disgusted with the new Popular Front government under the hapless Léon Blum (or “Jew Blum,” as snooty Time magazine called him). Then these French athletes march on – eyes right! – with perfectly choreographed Roman salutes as they pass the Führer at the reviewing stand. The crowds in the Berlin stadium clap and cheer loudly. Austria and Italy give the same salute, of course; but this is France.

Only trouble is, that’s not what was really going on. I was a victim of my own wishful thinking. All the teams were supposed to dip their national banners in salute to the host; perhaps the French tricolor drooped just a little too far. And that salute that the French team gave to Hitler and company was merely the “Olympic salute”: your right arm fully extended à droite. Olympic teams had been doing this for decades. After Berlin, however, the International Olympic Committee decided it might be a good idea to abolish it.

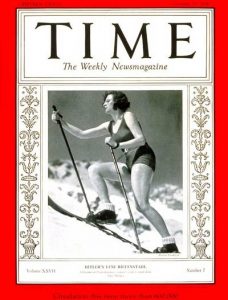

[2]As I review press clips for Leni Riefenstahl over the decades, I find myself faced with similar misconceptions. I had thought she had pretty much been treated as a villain, an outcast, someone never written about without a verbal sneer and spit. But this is not the case at all. When Time magazine had its 75th anniversary celebration [3] at Radio City Music Hall in 1998 with hundreds of still-living cover subjects, Leni Riefenstahl was there, as one of its most celebrated and honored guests, along with such equally notorious cover-cuties as Julia Child, President Bill Clinton, and Sean Connery. There was no finger-wagging in the press about how Leni had been a friend of Hitler’s who had filmed Nuremberg rallies. She was now 95, and Time Inc. was very happy to have her.

[2]As I review press clips for Leni Riefenstahl over the decades, I find myself faced with similar misconceptions. I had thought she had pretty much been treated as a villain, an outcast, someone never written about without a verbal sneer and spit. But this is not the case at all. When Time magazine had its 75th anniversary celebration [3] at Radio City Music Hall in 1998 with hundreds of still-living cover subjects, Leni Riefenstahl was there, as one of its most celebrated and honored guests, along with such equally notorious cover-cuties as Julia Child, President Bill Clinton, and Sean Connery. There was no finger-wagging in the press about how Leni had been a friend of Hitler’s who had filmed Nuremberg rallies. She was now 95, and Time Inc. was very happy to have her.

The year before that, Riefenstahl had gone to Los Angeles to receive a tribute at a film festival. While there was routine outcry from the expected sources (mainly Rabbi Abe Cooper of the Simon Wiesenthal Center), these protests were mainly laughed at.

It was around this time that there was an ersatz scandal in Hollywood surrounding a new Brad Pitt movie, Seven Years in Tibet, dramatizing the adventures of an Austrian skier and mountain climber named Heinrich Harrer. Shortly before the film’s premiere in LA, it was revealed that the bold mountaineer had once been in the SS. Worse yet, he’d once appeared in a skiing documentary by Leni Riefenstahl.

Writing in The Spectator in 1997 [4], William Cash treated the whole Riefenstahl/Harrer hoohah as a marvelous joke:

Only last month, LA’s Jewish Rage lobby became highly agitated when it was discovered that Leni Riefenstahl had made an unpublicised visit to receive an award at an LA film festival. Harrer was contracted to appear in a film Riefenstahl made about skiing in 1938. ‘They sneaked her into town,’ fumed Rabbi Cooper.

To placate LA’s militant rabbi faction, a would-be diplomatic photo-opportunity meeting was set up in Vienna between the Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal and Herr Harrer. Wiesenthal was left unimpressed by Harrer’s efforts to explain why he had kept his past hidden for 50 years . . .[1] [5]

One gathers that Harrer’s real offense was not nominal membership in the Schutzstaffel, but appearing in a Leni Riefenstahl movie.

Even when she died in 2003, Riefenstahl got little more than a perfunctory “naughty-naughty” in her New York Times obituary [6], and that showed up mainly in the headline (“Leni Riefenstahl, Filmmaker and Nazi Propagandist, Dies at 101 [6]”). Much of this obituary is devoted to the fact that she took up scuba-diving at age 71, and sparked controversy with a photographic book of naked Africans (The Last of the Nuba, 1974). And then, inevitably, there is a reference to the long-winded philippic that Susan Sontag wrote about her, “Fascinating Fascism [7],” in The New York Review of Books in 1975. In death as in life, what was newsworthy wasn’t so much Riefenstahl or her work, but rather what people were saying about her.

What really comes out, in seventy-odd years of Riefenstahl newspaper files, is that she always tried to keep a firm hand on her publicity. Her efforts were not always successful. Shortly before visiting Southern California in 1938 (to visit friends, she claimed, but also to promote Olympia), she had it put about that she had been denounced by Joseph Goebbels. According to the wire-service stories, Dr. Goebbels claimed to have discovered that Leni had some Jewish blood, way back there. We find Goebbels having her evicted from a Berlin cocktail party, declaring that he could not remain while there was a non-Aryan present. (The truth of the matter seems to be that Leni was a tiny bit Polish.)

This widely-publicized tale was such transparent press-flackery that it’s not surprising that the “Jewish Leni” story had been pretty much forgotten by the time she got to Hollywood. Anyway, the studios weren’t having any of it – or her; the “Jewish Rage lobby” took out ads in the trade papers, demanding that producers have nothing to do with Fräulein Riefenstahl. The only one who met her, one reads, was Walt Disney [8].

The 1950s and ‘60s were a relatively quiet time for Riefenstahl. While she couldn’t make movies anymore, she wasn’t being slammed as a Hitlerite villain, either. Or rather, when she was, these attacks always seemed to be Red-inspired, and were identified as such. In 1960, Britain’s National Film Theatre was forced by Communist pressure to cancel a Riefenstahl lecture. This prompted some head-scratching in the press: Why do we allow Communists to speak, but not someone who was friends with the Nazis? Asked columnist Keith Kyle in London: “Should the fact that she is a German make her ineligible to the tolerance due to a politically deviant artist of another nationality?”[2] [9]

Paradoxically, Riefenstahl’s most enduring negative criticism came from someone who had made her own reputation, in part, by defending Riefenstahl’s work. That critic was Susan Sontag. As in the New York Times obituary mentioned above, Sontag’s long anti-Leni bill of particulars from 1975 has a way of popping up in every critical study and biographical treatment of the filmmaker. Sontag’s pretend-outrage was based on Riefenstahl’s continued insistence on telling her own story: e.g., she was never a Nazi, but she liked Hitler, didn’t get along with Goebbels, and wasn’t going to apologize for any of this. There are many amazing passages in the Sontag screed, but the key one is probably this:

[W]hether or not Riefenstahl deserved a prison sentence, it was not her “acquaintance” with the Nazi leadership but her activities as a leading propagandist for the Third Reich that were at issue.[3] [10]

So she was a propagandist? This runs completely counter to the provocative pro-Riefenstahl argument that Sontag had made a decade earlier (see below). Rhetorically, we must ask why. And the answer is: feminism! Not the nonsensical Leftism that masquerades under that name today, but the old-fashioned formula, which in its time at least purported to be interested in gifted women who went against the grain. And near the top of the list you’d always find Leni Riefenstahl, the one outstanding female filmmaker of the twentieth century. By 1973 and 1974, she was being written about and honored at “women’s film festivals” in Telluride and New York, and few people seemed to be complaining.

This was a perfect opening for Sontag the contrarian. Her real target was feminism’s trendiness, but that agendum got lost in her massive attack on Riefenstahl, in a review that wasn’t even about Riefenstahl’s film career, but ostensibly covered Riefenstahl’s new photo book, The Last of the Nuba.

There are many glorious nuggets in this maddening seven thousand-word essay. Let me offer a couple:

Fascist art glorifies surrender, it exalts mindlessness, it glamorizes death. Such art is hardly confined to works labeled as fascist or produced under fascist governments. (To cite films only: Walt Disney’s Fantasia, Busby Berkeley’s The Gang’s All Here, and Kubrick’s 2001 also strikingly exemplify certain formal structures and themes of fascist art.)

Nazi art is reactionary, defiantly outside the century’s mainstream of achievement in the arts. But just for this reason it has been gaining a place in contemporary taste. The left-wing organizers of a current exhibition of Nazi painting and sculpture . . . in Frankfurt have found, to their dismay, the attendance excessively large and hardly as serious-minded as they had hoped. Even when flanked by didactic admonitions from Brecht and by concentration-camp photographs, what Nazi art reminds these crowds of is – other art of the 1930s, notably Art Deco. . . . The same aesthetic responsible for the bronze colossi of Arno Breker – Hitler’s (and, briefly, Cocteau’s) favorite sculptor – and of Josef Thorak also produced the muscle-bound Atlas in front of Manhattan’s Rockefeller Center . . .[4] [11]

Goodness, everything is fascist or Nazi, it seems. But I come back now to my main point, which is that Sontag was trying to walk back her earlier defense of Riefenstahl, published in Partisan Review, where she first made her name. Her first big-think piece there was something called “Notes on Camp [12],” which, apart from “Fascinating Fascism,” may still be her best-known essay. It’s mainly just a long “listicle” in which she enumerates about a hundred pop-culture totems (Tiffany lamps, Scopitone films, the Brown Derby restaurant) that she believes to be infused with a kind of male-homosexual ironical sensibility. There’s that famous line: “Camp sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a lamp, but a ‘lamp’; not a woman, but a ‘woman.’”[5] [13]

That was in 1964. The following year, she followed up with an essay on a similar theme, “On Style [14].” And here we find her enduring politics-be-damned critical defense of Leni Riefenstahl.

Sontag’s pro-Leni thrust is, essentially, that whatever you may think of the “Nazi” content of Triumph of the Will [15] or Olympia (which she calls The Olympiad) is really beside the point, and has no place in critical judgment. An artist needs material, content, sculptor’s clay to work with, and Riefenstahl’s material just happened to be memorable, eye-catching spectacle:

In art, “content” is, as it were, the pretext, the goal, the lure which engages consciousness in essentially formal processes of transformation.

This is how we can, in good conscience cherish works of art which, considered in terms of “content,” are morally objectionable to us. . . . To call Leni Riefenstahl’s The Triumph of the Will and The Olympiad masterpieces is not to gloss over Nazi propaganda with aesthetic lenience. The Nazi propaganda is there. But something else is there, too, which we reject at our loss. Because they project the complex movements of intelligence and grace and sensuousness, these two films of Riefenstahl (unique among works of Nazi artists) transcend the categories of propaganda or even reportage. And we find ourselves – to be sure, rather uncomfortably – seeing “Hitler” and not Hitler, the “1936 Olympics” and not the 1936 Olympics. Through Riefenstahl’s genius as a film-maker, the “content” has – let us even assume, against her intentions-come to play a purely formal role.[6] [16]

A purely formal role! In other words, the films are not themselves political; they are rather documentaries about things that might or might not have political or propagandistic content. You need to stand back from them, as from a painting at a museum, to appreciate them fully. This parallels Sontag’s description of Camp irony: where you see not a woman, but a “woman”; not Hitler, but “Hitler.” The film “Hitler” is okay, because he’s just an actor or icon, unconnected to those nasty Nazis you see in Hollywood.

The argument is a bit tortured, but you get the point: Sontag likes Riefenstahl, and so should any fair critic. But when the time came for her to write “Fascinating Fascism,” Sontag had to forget her old precept and argue a new rule: content matters, content is all. Hence her long, tortured tangents about the fascism of Walt Disney, Stanley Kubrick, and Busby Berkeley, or Art Deco and Rockefeller Center.

Whether she really believed any of her later silliness or was just trying to entertain the reader is an open question. But her two contradictory arguments survive as the two popular poles of thought about Leni Riefenstahl.

Of course there’s a “third pole” of thought, too: Riefenstahl was an artist, and her content is fine. And her work needs no abstruse critical theory to justify it.

Notes

[1] [17] William Cash, “Brad Suddenly Turns Nazi [4],” The Spectator (London), October 11, 1997.

[2] [18] Keith Kyle, “Not for Export,” syndicated column in New York Post, January 15, 1960.

[3] [19] Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism [7],” The New York Review of Books, February 6, 1975.

[4] [20] Susan Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism.”

[5] [21] Susan Sontag, “Notes on Camp [12],” Partisan Review (New York), No. 4, 1964.

[6] [22] Susan Sontag, “On Style [14],” Partisan Review (New York), No. 4, 1965.