Once Upon a Time in Little Italy:

The Family Noir of House of Strangers

Posted By

James J. O'Meara

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

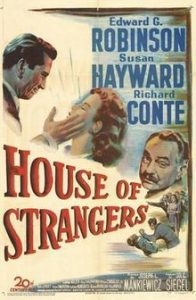

House of Strangers (1949)

Directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz

Written by Philip Yordan (screenplay), Joseph L. Mankiewicz (rewrite, uncredited), & Jerome Weidman (novel)

Starring Edward G. Robinson, Susan Hayward, Richard Conte, & Efrem Zimbalist, Jr.

“As nasty a nest of vipers as ever you’re likely to see outside of a gangster picture or maybe a jungle film . . .”[1] [2]

What is film noir? And more to the point, is House of Strangers a film noir? It does make Wikipedia’s list of such titles [3], for what that’s worth; but even that source starts off with this disclaimer:

Film noir is not a clearly defined genre (see here [4] for details on the characteristics). Therefore, the composition of this list may be controversial. To minimize dispute the films included here should preferably feature a footnote linking to a reliable, published source which states that the mentioned film is considered to be a film noir by an expert in this field.

And there it is, with two “reliable, published sources” to back it up. Still, we seem to be in Potter Stewart’s “I know it when I see it [5]” territory, or perhaps we could avail ourselves of Wittgenstein’s notion of family resemblances [6] to explicate the genre. That would be appropriate here, as what’s odd – to me at least – is a film noir approach to what is basically a domestic business drama; sort of like if Buddenbrooks had been filmed in the style of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

I confess that what interested me initially in the film, which was recently shown on TCM, was that the cable guide synopsis led me to think this was a Hollywood treatment of the Rothschilds, under the usual crypsis of having Jews portrayed as Italians; perhaps I had been primed [7] by reviews of the recent Broadway musical thereon [8].[2] [9] Indeed, Robinson (aka Emanuel Goldenberg, born on Dec 12, 1893 in Bucharest, Romania) almost specialized in playing various goyishe immigrants (usually criminals), starting with Little Caesar (LeRoy, 1931).

Here’s the overview from TCM [10]:

Lawyer Max Monetti (Richard Conte) was always the favorite son of his domineering, self-made neighborhood banker father Gino (Edward G. Robinson) . . . and when Gino went up on trial for usury, Max’s attempt at jury tampering cost him career and freedom. Now out of prison, Max sets out to settle accounts with the resentful brothers (Luther Adler, Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., Paul Valentine) who’ve commandeered the family business.

Wikipedia [11] puts a little more flesh on those bones:

Gino Monetti is a rags-to-riches Italian-American banker in New York whose methods result in a number of criminal charges. Three of his four grown sons, unhappy at their father’s dismissive treatment of them, refuse to help Gino when he is put on trial for questionable business practices. Eldest son Joe seizes control of the bank and brothers Tony and Pietro side with him. Max, a lawyer, is the only son who stays loyal to his father.

The brothers conspire to send Max to jail as well. Max tries to bribe a juror to save his father, but gets disbarred and serves a stretch of seven years in prison. Max must leave behind Maria (played by 15-year old Debra Paget [12]), the girl he had been expected to marry, and Irene, a client he fell in love with after becoming her attorney.

Max vows revenge on his brothers, but when he is released Max has a change of heart when he realizes that his father had caused all the tension within the family. The three brothers, however, are still worried about his quest for vengeance, and Joe even goes so far as to order Pietro to kill Max. In doing so, however, Joe insults Pietro in the same way their father always had, prompting Pietro to turn on Joe instead.

Max saves Joe from Pietro’s wrath by reminding Pietro that if he kills Joe, he would only be doing exactly as their father would have wanted. Max then leaves his brothers to rejoin Irene and travel to San Francisco [13], where they plan to start a new life together.

All this goyishe mishigas is a far cry from the Rothschilds, but does glancingly address an interesting question: How did all those Ellis Island immigrants get their business affairs set up? Alas, very little attention is paid to such mundane matters; indeed, that’s how Gino screws up.

But what really holds our attention is not Robinson’s Gino, but Max, as played by Richard Conte. Conte had a respectable career, including Northside 777 (Hathaway, 1948), The Big Combo (Lewis, 1955, and a personal favorite of mine), and several Sinatra films, including Ocean’s Eleven (Milestone, 1960).

Most folks out there, however, will likely recognize him from one of his last roles: Don Barzini in The Godfather (Coppola, 1972).[3] [14] Indeed, Conte provides us with links to two later, more authentically Italian films in the gangster genre: The Godfather and Once Upon a Time in America (Leone, 1984).

First, The Godfather; as an online critic said [15] just a few months ago:

The expansive Italian family rendered so memorably in The Godfather films comes to mind most plainly and there’s little doubt House of Strangers sows some of the same seeds cropping up again over 20 years later in Coppola’s classic.

Another spells it out [16] a bit more:

This surprising dysfunctional family noir from Joseph L. Mankiewicz foreshadows “The Godfather” in many ways. Edward G. Robinson is an Italian immigrant who has risen through the ranks of the lower East Side where Gino’s Bank is financial refuge to those with no collateral. Gino is visited by people of the neighborhood all asking for favors as if he were Don [Corleone], and like Don Corleone, while Gino looks out for women and children, his ‘favors’ come with a price.

That sounds a bit too sinister. Indeed, the key difference between Gino and Vito is that Vito’s enterprise is both criminal and well thought out from the start; Gino simply has no patience with bookkeeping, or following any kind of rules, including even the primitive pre-1933 banking laws. Like an ‘80s savings and loan, or a 2000s real estate firm, Gino gives loans to folks with little or no collateral and with little or no hope of ever paying him back; kept on the books for years, the loans become usurious through sheer inattention.

When eventually there’s a run on the bank, the scene plays out like a parody of It’s a Good Life: Gino runs out into the crowd, grabbing people and telling them how he saved their businesses, and so on, but discovers they resent his loansharking and even begin to beat him up.[4] [17]

Robinson does a good job with the script he’s given, but it’s the sort of role where you know he’s Italian because he plays loud opera records incessantly,[5] [18] hosts a weekly spaghetti dinner for the whole family and in-laws, and talksa likea thisa. It’s the sort of thing Coppola wanted to eliminate from the genre.[6] [19]

But, as the previous critic says, it’s the family that comes to mind, and our second critic moves on to that:

Gino also manipulates his sons, keeping them under his thumb with the promise of the bank as their inheritance. In the meantime, he keeps eldest, Joe, in check as a teller (‘Get back to your cage!’) despite the promise of a raise when Joe married (to WASPy Elaine (Diana ‘mother of Michael’ Douglas) who expected a moneyed lifestyle). Pietro, an amateur boxer, is ordered about, called a ‘dumbhead’ and stripped of his Monetti robe when he loses the bout dad’s finally come to see. Tony is a flash guy who tries to keep the peace but without much conviction. Max, however, is on his own as a lawyer, engaged to good Italian girl Maria (Debra Paget, “Love Me Tender”) when he falls under the spell of client Irene Bennett (Susan Hayward).

It’s at home that Gino reveal his monstrous side; he seems to have no interest in preparing his sons to take over his – as he supposes, legitimate – business; instead, he indulges in petty tyrannies even beyond those listed in the quote: Joe must wash his back, and Pietro is only good for getting up to change the 78s. The film never addresses the reason for this treatment, not even some hackneyed “I wanted to toughen you up” sort of excuse. It implies that this is just Old World tradition; again, the sort of thing Coppola wanted to upend.[7] [20]

The Godfather is quite different. In line with Vito’s intelligence, he has a clear plan for succession. Sonny, though a hothead, will be the next Don, hopefully held in check by Tom as consiglieri. Fredo is, well . . . And Michael was to be “Senator Corleone, Governor Corleone.” Of course, things don’t work out that way; hence, the drama.

It’s interesting, though, to see how the same family dynamics are present in House of Strangers; family resemblance! Joe, the heir apparent, is hardly a Sonny, and he’s the one married to a WASP like Michael’s Diane Keaton. “Dumbhead” Pietro is, well, Fredo, but unlike Fredo, he will, in the end, refuse to be manipulated into killing Max, who, in turn, is Michael.

Max obviously also absorbs Tom’s role, by becoming not a war hero but a lawyer. Like Michael, he seems to be his father’s favorite, as much as one could be. It’s interesting that while Gino seems like a nice guy (in business, not so much at home) who just got in over his head (rather than, say, “breaking bad”), Max, when we first see him in the main flashback section, appears to already be a somewhat shady attorney; Hayward needs his services for the same reason Lauren Bacall seeks out private eye Bogart in The Big Sleep, or Faye Dunaway seeks out Jack Nicolson in Chinatown. By the end of the flashback, he’s trying to bribe a juror. But we’re supposed to root for him – or, at least, as Chris Rock said about OJ, understand him – since it’s to help his father; conversely, Joe’s ratting him out isn’t him being a good citizen, since it’s his brother, and he’s trying to ensure his father’s conviction and take over the business; Joe is ultimately Fredo – we can hear his WASP wife shrieking, like Fredo’s, “Never marry a wop!”

Max tries to help his father (Michael avenges his father), is betrayed (by Joe, not Pietro/Fredo), gets sent to jail and thus loses his Italian fiancée (Michael avoids jail by being exiled to Sicily, where he takes up with Apollonia, who is killed before he returns from exile), but finds a new life with his rich, WASP client (Diane Keaton again).[8] [21]

Oh, yeah, there’s Tony; he’s good with the ladies, like Sonny, but more of a lounge lizard than macho stud, winding up with Max’s Italian girl.[9] [22] He doesn’t have much to do, and it’s a surprising role for Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., who would later come to symbolize J. Edgar Hoover’s idealized FBI on the eponymous TV show.[10] [23]

But what about Once Upon a Time in America? Supposedly Leone was sick of Hollywood making movies about Italian gangsters, and decided to remake Godfather II from Hyman Roth’s perspective. Crypsis again; now call me an ignorant bigot, but “Max” just doesn’t sound like an Italian name to me, but it’s a resoundingly appropriate name for the main Jewish gangster in Leone’s epic, with his syphilis-inspired megalomania. But don’t be fooled: The “Max” role in Leone’s film is not played by the character Max but the not-so bad gangster, unfortunately named Noodles, and played by Godfather II ’s young Vito, Robert DeNiro.

There’s no real family of any sort in Once; the band of brothers is metaphorical, as in a criminal Männerbund. In House, Max tries to (dishonestly) defend his father, is betrayed by brother Joe, goes to jail, and when he returns the bank is under new, fraternal management. This is split up and redoubled in Once. Noodles is sent to prison when he instinctively tries to kill the cop who shoots one of the gang; when he returns, Max II (I’ll call him James Woods from now on to prevent confusion) has expanded the gang’s operations. Now Woods wants to take the gang into the big time by joining up with the Italian mob, just as Joe wants to take over the bank (the first Italian gangster who hires Wood’s gang is named Joe); Noodles reluctantly goes along. Ultimately, Woods wants to take over another kind of bank: to rob the Federal Reserve Bank in New York. Noodles is forced – to prevent Woods from making this hubristic mistake – to betray him to the cops, with disastrous results. He spends thirty years hiding out (in Buffalo: “the asshole of the world”) but returns to confront Woods, who had actually betrayed him (as Joe betrays Max), taking his girl as well (as Tony takes Max’s fiancée).

Whoa! Well, if you’ve seen the film, you know that’s exactly how complicated it is; the layering of past and present makes Pulp Fiction seem like a Lifetime Channel movie.[11] [24] The flashback technique links all three films and provides the clearest noir characteristic, with House being relatively straightforward, told mostly in flashback with a framing story in the present (Max’s return and confrontation with his brothers), and Godfather II using a somewhat more elaborate structure of alternating relatively long chunks of past and present.

The other link between House and Once is the dénouement. Both take place on the top floor of a mansion built by ill-gotten gains.[12] [25] As noted, Woods has, like the brothers, utterly betrayed Noodles:

“I took away your whole life from you. I’ve been living in your place. I took everything. I took your money. I took your girl. All I left for you was years of grief over having killed me. Now, why don’t you shoot?”

Max, having reflected on his life (the movie’s central flashback, taking up most of the running time), has realized that it was their father who was to blame for their rotten upbringing, and he forgives his brothers – like Don Corleone, he “forgoes the vengeance.”[13] [26] He even saves Joe from Pietro’s wrath by reminding Pietro that if he kills Joe, he would only be doing exactly as their father would have wanted.

Noodles, too, realizes he would rather have the memory of his best friend (his former girl, now Wood’s mistress, has told him that “All that we have left now are our memories”) than acknowledge his betrayal in order to exact revenge, even if that’s exactly what Woods wants from him:

You see, I have a story too, Mr. Bailey [Woods’ alias]. I had a friend once. A dear friend. I turned him in to save his life. He died. But he wanted it that way. Things went bad for my friend, and they went bad for me, too.

Well, that’s how it is in the movies.[14] [27] This was not Michael Corleone’s choice: “I don’t feel I have to wipe everybody out, Tom. Just my enemies.” The middle films in our ad hoc trilogy – The Godfather Saga – seem to be the least “Hollywood” in morality. Although things don’t go so well for Michael (if we take Godfather III as canon, rather than pretending, as most do, that it never happened), we can note that neither Noodles nor Max have families or businesses – or nations – to look out for.

The reader can decide for himself whether to take Rabbi Yehoshua or Machiavelli for his guide. Either way, you’ll find House of Strangers to be an excellent way to spend 100 minutes or so while waiting for the next item to appear on Counter-Currents.

Notes

[1] [28] Bosley Crowther, “Richard Conte, Susan Hayward, Edward Robinson in ‘House of Strangers’ at Roxy [29],” The New York Times, July 2, 1949. “On the stage at the Roxy are Janet Blair, the Blackburn Twins, the Martin Brothers, Herb Shriner, the Roxyettes and an ice show featuring Carol Lynne.” Now that’s entertainment!

[2] [30] There was an earlier one, in 1970. Apparently [31], Fiddler on the Roof’s “If I were a Rich Man” was originally “If I were a Rothschild.”

[3] [32] According to IMDB, he was originally up for the lead, with Laurence Olivier and Marlon Brando. As another claim to pop culture fame, the first artistic rendering of James Bond (the Pan paperback cover of Casino Royale in 1955) was based on Conte [33]; or, as another source has it [34], “Richard Conte’s face with Daniel Craig’s blond thatch.”

[4] [35] It’s also bit like the Fawlty Towers episode where the guests turn on Basil: “I’m not satisfied!”

[5] [36] The family no doubt would welcome an appearance by Mike Hammer, smashing poppa’s precious 78s one by one; see “Mike Hammer, Occult Dick: Kiss Me Deadly as Lovecraftian Tale [37],” reprinted in my collection The Eldritch Evola . . . & Others: Traditionalist Meditations on Literature, Art, & Culture [38]; ed. Greg Johnson (San Francisco: Counter-Currents, 2014).

[6] [39] I don’t know if Robinson deserved an award from Cannes, but he really does inhabit his role; you can see the contrast in the scenes with his wife, where the actress is clearly just playing a role. He need make no excuses to Brando or DeNiro.

[7] [40] There are hints at it when Vito upbraids Sonny at the sit-down with Sollozo:

Don Corleone: I have a sentimental weakness for my children, and I spoil them, as you can see. They talk when they should listen.

[Sollozzo leaves after the Don wishes him luck]

Don Corleone: [to Sonny] Whatsa matter with you? I think your brain’s goin’ soft . . . Never tell anybody outside the family what you’re thinking again.” Actually, Vito alludes to “tradition” to disguise Sonny’s faux pas (Sollozzo must not think anyone in the family knows anything) and then uses it to indeed teach Sonny something about the business.

[8] [41] It’s a small, early role for Susan Hayward, with not much more to do than fill the role of WASP temptation, but she’s nice to look at and her dialogue with Conte is pretty snappy.

[9] [42] Played, as noted above, by the 16-year old (some sources say 15-year old) Debra Paget; an oddly contemporary note, and also related to The Godfather’s pedophiliac producer, Jack Woltz.

[10] [43] See “‘Mueller, Do You Realize What This Means?’ Reflections on Brett Kavanaugh & the ‘Intergalactic Freakshow [44].’”

[11] [45] Like Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons, it was taken away and butchered by the studio, who re-edited it into chronological order (like Coppola’s “special edition” of the Godfather Saga), the awful result thereby proving the superiority of Leone’s Einsteinian storytelling; if you really can’t follow it, you’re too young to be going to movies by yourself.

[12] [46] Woods is revealed on his balcony, then the rest of the scene is indoors; Max confronts his brothers on the first floor, is attacked by them, and then taken to the second-floor balcony with the intention of throwing him over. Critics have noted that a twenty-foot fall might not be a sure plan for killing someone.

[13] [47] Sort of. As he tells Barzini: “But I’m a superstitious man, and if some unlucky accident should befall him . . . if he should be shot in the head by a police officer, or if he should hang himself in his jail cell [like Jeffrey Epstein?], or if he’s struck by a bolt of lightning, then I’m going to blame some of the people in this room, and that I do not forgive. But, that aside, let me say that I swear, on the souls of my grandchildren, that I will not be the one to break the peace we have made here today.” And we know how that turned out: Michael, Max’s doppelganger, will kill, among others, Barzini, played by Richard Conte.

[14] [48] Bosley Crothers (op. cit.) didn’t buy it back in 1949: “Max, who is early demonstrated as a man coldly bent upon revenge, is suddenly turned into a softie by an hour or so of reverie.”