Now in Audio Version! Rammstein Needs to Retire

Posted By Scott Weisswald On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledTo listen in a player, click here [2]. To download the mp3, right-click here [2] and choose “save link as” or “save target as.”

More on Rammstein at Counter-Currents here [3].

Du hast mich gefragt, und ich antwortete: Rammstein needs to retire.

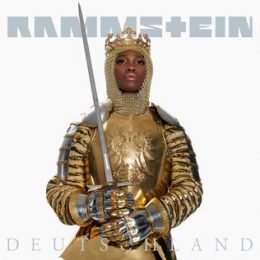

Coming on the heels of a long hiatus, Rammstein’s new self-titled (or untitled, depending on who you ask) album is more a testament to how tired Rammstein’s shtick has become than an invigorating piece of heady, wild metal. Rammstein broke their silence with the lead single off this record, “Deutschland,” which featured cover art depicting a black woman wielding a sword. The quality of this album was therefore rather easily predicted. Rammstein hasn’t truly been relevant since the very early 2000s, and largely depended upon performative hyperbole and their rough, “German” image that lends them some degree of exoticism and perceived genuineness among the audience they found abroad. Put simply, Rammstein has never been much more than a relatively gimmicky Neue Deutsche Harte band that found unlikely success globally with a sound that relied on the same tropes as any other metal-goes-pop outfit – with an extra dash of helpful stereotyping. In Till Lindemann’s own words, “German is the language of anger.”

This attitude towards one’s own homeland is in clear focus on this record, beginning the circus with the aforementioned lead single “Deutschland,” which opens in one of the most poetic ways possible: A reference to the band’s largest single to date. The opening lines, “Du hast . . .,” convey just how creaky the band’s joints are in a way that no critic ever could put into words. Of course, to the average Rammstein listener, this is fan service at its finest; playing off the nostalgia of their initial forays into fame in order to give this newest effort even a slight claim to legitimacy. The unfortunate truth is, however, that Deutschland sounds more like a passable Linkin Park B-side than a skull-crushing East German power trip, if one is to ignore Lindemann’s growling about du, ich, and wir, or his tongue-in-cheek “Deutschland über allen,” followed, of course, by the most telling line of the entire song: “Ich kann dir meine Liebe nicht geben,” or in English, “I cannot give you my love.” It’s rather difficult to tell who this music is being made for: Germans who legitimately dislike their own homeland? Clueless Americans who have no idea what is even being said? The instrumentals are entirely lackluster, and would probably be better received as some kind of dance-rock or hardcore club tomfoolery than “metal,” so this is certainly not meant for rabid headbangers, either. Rammstein, despite their manufactured German image, is yet another rootless, globalized hit machine churning out music that will burst across the radio waves and then be forgotten within the span of the next record cycle.

Speaking of radio, the album’s second entry, “Radio,” opens on rhythm guitar and square synth, a formula that doesn’t change much throughout the 4 minutes and 37 seconds of a song that amounts to little more than a chorus clearly designed for catchiness and not much else (“Radio, mein Radio”) and occasional power chords. The verses that make up this track all follow the same uninspired cadence, and again touch on the most boring, safe topics possible: music, the radio, keine Grenzen (no borders). For a band that previously prided itself on shock value and dealt with such publicly reviled topics as violence both physical and sexual, personal hate, and pyromania, safe subjects like free love and open borders seem incredibly out of place. One could ramble on endlessly about Rammstein’s music and how poorly it has aged, but if any one thing is to be cited when calling for the band to lay down their instruments, it’s the fact that they’re writing songs about European establishment talking points. If you’re supporting the status quo, posing as some kind of subversive, edgy group is nothing more than that: posing.

“Zeig Dich” initially offers something a bit more listenable given the juxtaposition of an operatic wail with grating rhythm guitar work, but unfortunately, the countless artistic directions one could have taken with such a track are thrown out the window in favor of a dusty, endlessly-repeated pop metal formula consisting of power chords, two-syllable mantra choruses, and an entirely uninspired melody that hits every safe spot in its key in arpeggio fashion. There really is not much to say about this song: No one section particularly stands out, but there’s nothing to be gleaned from the track as a whole, either. On every quarter note, a kick drum. Every half note, a snare drum. Hi-hats roll in between. Distorted guitars and phlegm-choked utterances from the back of the throat coat the remainder of the track until the very end, when the opera returns; and once it’s all been said and done, one can’t help but think that it’s quite a shame the opera had to go away at all.

The forebodingly-named “Ausländer” (foreigner) tells the story of a man at home “everywhere,” a man whose language is “international.” No matter where he goes, he is an Ausländer, a word of contention in Germany. There is no way to get through this track without cringing; it oozes with a pallid, painfully white brand of internationalism that consists of vague references to one’s own mystery, relying on the mythos surrounding a man who spends only a few hours in each town, and a chorus composed in German, English, French, and Russian. No other group of people on Earth feel like this other than a small group of cosmopolitan, equally self-loathing yet narcissistic white folk who have access to money. Overall, “Ausländer” is a perfect representation of the state in which much of Europe lies: People who don’t feel at home where they’re from, and pride themselves on being “foreign” in the other lands they meander too. We can only wonder if Lindemann is aware of the irony that his ditty used only European languages in its chorus.

The charmingly named “Sex” provides a momentary reprieve – if one revels in kitsch. It’s a bit of a throwback to the edgy, earlier days of Rammstein, driven by a vaguely sensual bassline with the tops of its frequency range lopped off. Lyrically, the song covers every aspect of what Rammstein must imagine a sexual encounter is like, from flirting (plenty of the song is a compliment about a woman’s breasts or genitals) to ecstasy (screaming “Sex!”), and finally, hedonistic nihilism (“We only live once”). Alas, what surely would have been a real stickler in the sides of parents and the suited public in the ‘90s is now almost milquetoast. In an era full of child drag queens, public sex acts in the name of “pride,” and countless smartphone applications dedicated to the most meaningless and casual sex possible, a song about heterosexual desire is far from edgy, provocative, or even remotely interesting. Men in their 50s yelling about breasts might inspire a Boomer or two, but to everyone else, it just sounds like noise.

“Puppe” may be the worst offender on the album when it comes to watered-down production. This track features literal trap instrumentals: a snare drum on the second and fourth note with syncopated kick drums dancing about it. There is, however, one particularly graceful moment on this song and the record as a whole: For once, Rammstein decided this album deserved a deconstructed, crunchy reprieve from a vaguely synthetic bassline and the same power chords, and for about ten seconds we’re given headache-inducing drum-pummeling and Lindemann gutturally bemoaning his own behavior of biting out the neck on a doll, almost as if he was gasping for air, suffocating under the weight of his own persona. This moment of random ingenuity doesn’t last long, however, and the rest of the song takes on a doom-like atmosphere, rolling out the same tropes, tricks, and traditions that have marked every generic radio-friendly metal song over the last two centuries. Who knows what the story behind “Puppe” is; we may only ponder what it might have been.

“Was ich liebe” takes on a Volbeat-like composition, drowned in atmosphere and effect to the point that nothing is discernible on its own except for a synth melody that appears about midway through that inescapably sounds like Billie Eilish, once you make the comparison. Of course, since Rammstein doesn’t like sticking to the same cliché for long, atmosphere is broken up by diluted rhythmic slamming or pedaled plucks on the high side of a guitar. In terms of messaging, there is not much to say other than that this song attempted to be depressing, with whiny verses about how the things you love shrink away from you. It makes sense, then, that this song seems to go on for so long.

“Diamant” is an attempt at a downtempo, brooding love song. On no front is Rammstein more deserving of criticism than in its incredibly tired set of formulas and clichés, and this is painfully apparent on “Diamant,” with descriptions of one’s object of desire as a “diamond” and the typical, bland Gen X pessimism of decreeing that a diamond is “just a rock.” This track is the shortest on the album, at 2 minutes 34 seconds, and deserves some credit for fizzling out after it finished making just one round about its exhausting songwriting, rather than the seemingly endless repetition of the album’s other cuts.

“Weit Weg” begins almost like a Paul Kalkbenner transition track. This is quickly thrown out in favor of a pseudo-hair metal approach, offering all of the cringe and none of the nostalgia. A sweeping, organ-programmed synthesizer plods throughout the song’s key while an unenthusiastic Schneider drops his feet on the kick drum in the same pattern that he has for ninety percent of the album. Much like the other filler tracks on here, there isn’t much to say that hasn’t already been said. This song is tiring, uninventive, and completely forgettable. There isn’t even a hamfisted sociopolitical message to chew on; just more dreck. Perhaps that’s the real sociopolitical message.

“Tattoo,” the penultimate track, begins with a Slayer-like thrash opener and morphs into another – moderately ghastly – Rammstein track. Peppered with elementary metaphor, such as that of writing a letter on burning paper (but the paper is one’s skin!), “Tattoo” is a prime example of Rammstein running out of material after exploring a new idea. It’s unfortunate that much of this record is conceptually interesting at its base, but every original idea that manages to peek its head out of the water is inevitably smothered in pop-metal building blocks. The end result is tracks only worth a second thought if they’re of boisterous annoyance (“Sex”) or self-important obliviousness (“Ausländer”). Hopefully, nobody tattoos any of the lyrics from “Tattoo” on themselves, unless they’re trying to prove a very important point.

“Hallomann” ends the record fittingly. Almost every confusing, boring, or misfit Rammstein patchwork used to stitch this album together happily prances back on stage, whether it’s the power chords, choral operatics (which, when listened to individually and together, sound nearly identical), unseasoned vocal cadence, or even public enemy number one, the syncopated and synthesized trap drumline. Generally speaking, a record’s last track is often an indication of a group’s future output, or is otherwise a closing rumination on an album’s themes, but it would appear that Rammstein opted instead for a filler track that runs the gamut of their previous sins, almost as if to remind us that we actually listened to this entire release.

Truth be told, the closing track’s intentions don’t matter all that much; you’re bound to forget just about all of this album in a few hours, anyway.