Breakfast at Tiffany’s

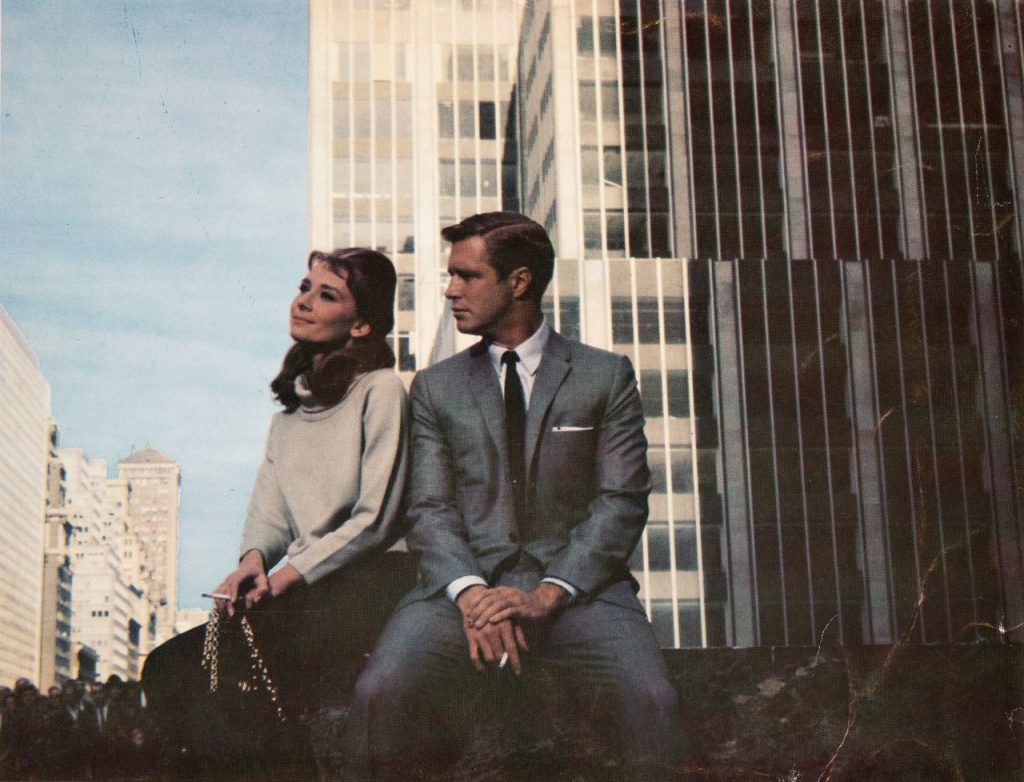

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledBlake Edwards’ 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany’s—loosely based on Truman Capote’s 1958 novel of the same name—stars Audrey Hepburn in her iconic role of Holly Golightly, a charming, flighty, feminine, haunted young woman trying to create a life—and an identity—in a gorgeous Technicolor New York City at what is arguably the peak of American civilization, just before the plunge.

I have seen Breakfast at Tiffany’s six times, twice on the big screen, and although I loved it every time, for the first four viewings, the movie played a strange trick on my memory. If you had asked me what Breakfast at Tiffany’s was about, I would have said it is a wholesome romantic comedy. But that’s not really true. Yes, it has plenty of comic elements, but overall, Breakfast at Tiffany’s is a very sad and serious film. As Sally Tomato says, the story of Holly Golightly’s life would be a book that “would break the heart.” That’s certainly true of Truman Capote’s novel, which is indeed so heartbreaking that Blake Edwards rewrote the ending for the movie to give us a little hope to cling to.

And, as for wholesomeness, it has that too in the end. But somehow I repeatedly forgot that Breakfast at Tiffany’s is the tale of the romantic misadventures of two gold-diggers, Holly Golightly and her upstairs neighbor, Paul Varjak, both of whom are skating through their 20s by having sex with and taking money from older and richer people. Of course, they both maintain their self-respect by keeping a discreet distance between the sex-giving and money-taking, so that the quid pro quo is not too brazenly obvious. Capote said that Holly stopped short of simple prostitution, describing her as an “American geisha.”

Both Holly and Paul rationalize their choices by reference to a mission. Holly wants to buy land and horses and care for her sweet but slow brother Fred, who is currently in the Army. (The novel is set in 1943, so being in the army is rather dangerous undertaking.) Paul is a writer who needs a patron to give him time to work on his great novel. But it is not working. He’s got writer’s block. As Holly notes, he doesn’t even have a ribbon in his typewriter.

Paul is the prouder and more serious of the two. Holly is top banana in the flake department. Which, of course, means that Paul suffered greatly at Holly’s hands when he falls in love with her.

Maybe the false memories are due to Henry Mancini’s music, which won two Oscars, for best score and best song for the haunting cornball classic “Moon River,” with lyrics of Johnny Mercer, which casts a silvery shimmer of nostalgia over the whole heartbreaking tale. Whatever the cause, I am grateful to this amnesia, for it has allowed Breakfast at Tiffany’s to surprise me again and again with each new viewing.

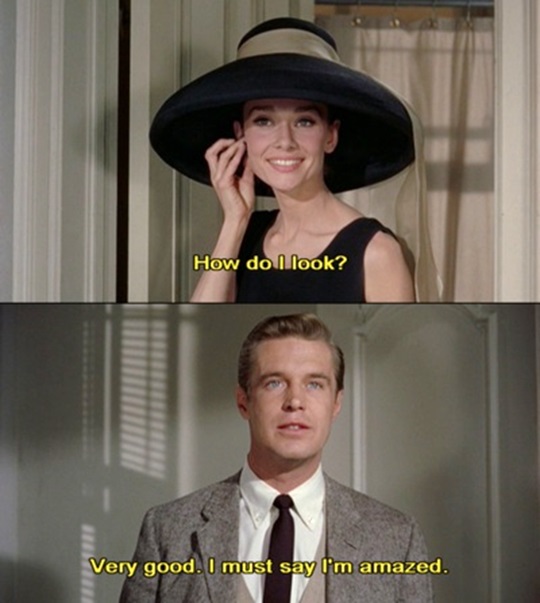

The basic plot of Breakfast at Tiffany’s is quite simple. Paul Varjak—played by George Peppard at the peak of his Nordic-preppy good looks—moves into an apartment on Manhattan’s upper east side and meets his ditzy downstairs neighbor, Holly Golightly. Holly has lived there for a year but looks like she is still moving in. That’s because she’s rootless, a drifter, a flake. She has an orange cat, but she hasn’t given him a name, because she doesn’t want the commitment. Her favorite place in the world is Tiffany’s, the jewelers on Fifth Avenue. She declares to Paul that if she ever finds a place that makes her feel like Tiffany’s, she’ll put down roots and give the cat a name. Of course it is hard to imagine a home that would feel like Tiffany’s. Buckingham Palace, perhaps? Holly, in short, is not too practical. Her conditions for settling down are a fanciful way of saying “never.”

Paul’s apartment isn’t exactly “him” either. It looks like an expensive European hotel room. It was decorated before his arrival by his patron, Mrs. Failenson, nicknamed “2E,” played by a radiant Patricia Neal (who once played opposite a certain Ellsworth Toohey in King Vidor’s film of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead). The movie creates the character of Paul from the novel’s unnamed narrator. 2E and her relationship with Paul are inventions of the screenwriter, which considerably deepens the character and his relationship with Holly, creating dramatic conflict through “irreconcilable similarities.”

Holly finds Paul to be a sympathetic, useful, and highly presentable neighbor. As fellow gold-diggers, they also have a certain understanding. But in her eyes, their shared mode of life also precludes a relationship, for Paul has no gold, and Holly has set her sights on older, uglier men with more money. For Paul, gold-digging is a short-term strategy, to get his start in life, at which time he will settle down with a nice girl and take care of her. For Holly, however, gold-digging is a long-term strategy to find a husband, who will take care of her forever.

One of the most captivating sequences in Breakfast at Tiffany’s is when a mysterious stalker shows up outside Paul and Holly’s building. 2E thinks her husband is having her followed. Paul, who is a red-blooded male under his gorgeous wardrobe, is game for a confrontation. After a game of cat and mouse in the east side and in Central Park, the stalker approaches Paul and says, “Son, I need a friend.”

It turns out that the stalker, played by Buddy Ebsen, is Doc Golightly, a veterinarian from Texas and Holly’s . . . no, not her father, her husband, whom she married at the age of 14. Holly’s real name is Lula Mae Barnes. Lula Mae and Fred were runaways who showed up on Doc’s farm. Doc was a widower with children who needed a helpmeet. Hence the marriage. Doc has tracked Lula Mae down to persuade her to return home to “her husband and her chirren.”

Holly will have none of it. The marriage was annulled long ago, and she’s just not Lula Mae anymore. She has constructed a whole new identity for herself. She got rid of her Okie accent with French lessons, courtesy of a Hollywood producer, O. J. Berman (Martin Balsam), and she has a fabulous circle of rich male friends—whom she rates as “rats” and “super-rats”—competing for her attention.

When she sees a heartbroken Doc off at the Greyhound Bus station, she tells him that she’s a “wild thing” and that one should never fall in love with wild things, because they will just break your heart. In truth, Holly is just a flake who doesn’t know who she is or what she wants and is afraid of real relationships and real commitments. Berman thinks Holly is a phony, but he debates whether she is a real phony or not—a real phony being someone who believes his own nonsense.

The whole sequence moves from creepy, to comical, to corny, to deeply moving. That’s the magic of this film.

Once Doc has been sent on his way, Holly gets roaring drunk. It is a catharsis, a crisis, a crossroads. Paul now knows her story but loves her all the more. He hopes that she will get a little more serious about life, and maybe about him. Paul enjoys taking care of Holly. It makes him feel strong and manly. Being taken care of by 2E is convenient but emasculating. Unsurprisingly, Holly proves to be the better muse than 2E. Awakening Paul’s manliness also awakens his creativity.

Thus Paul is appalled when Holly declares that she is no longer going to play the field. She is going to set her sights on marrying Rusty Trawler, the ninth richest man in America under fifty, despite the fact that he is a tittering pig-faced manlet. (In the novel, Trawler is a known Nazi sympathizer who once proposed marriage to Unity Mitford.)

When Trawler falls into the clutches of another gold-digger, Holly coolly turns to pursuing José da Silva Pereira (played by Spanish aristocrat José Luis de Vilallonga), a dashing but strait-laced Brazilian from a prominent family. It is not clear to Paul, though, if he means to marry her or merely keep her as a mistress. Holly is oblivious, however.

Whatever José’s intentions, however, he calls it off when Holly is arrested. Holly has received $100 per week to visit Sally Tomato, an elderly mobster incarcerated at Sing Sing, and deliver his “weather report”—obviously coded messages about the narcotics trade—to his people outside.

Berman gets Holly bailed out. Paul packs her belongings and the cat and picks her up at a police station to take her to a hotel where she can hide out from the press. In the cab, he breaks the bad news about José. While adjusting her lipstick, Holly coolly decides to jump bail, use her ticket to Brazil, and marry some other rich South American. In an act of consummate bitchcraft, she tells the cab to pull over and abandons the cat in an alleyway in a downpour. In the novel, she follows through with her plan and disappears. A realistic but terrible outcome that puts Holly Golightly into the lower circle of flaky heartless bitches like Cabaret’s Sally Bowles [7].

In the film, Paul gives Holly a powerful talking to. He tells her that people really do belong to one another and that it is the only real chance we have of happiness. In today’s rabidly individualistic society, these are unfashionable sentiments, but deeply romantic and stirring ones. Paul actually reaches Holly. He actually changes her heart. She runs into the rain, searching for the cat, whom she finds, then Paul and Holly embrace, the prototype of a human family that may come to be. (Holly definitely wants children.) The end—a happy one, we hope.

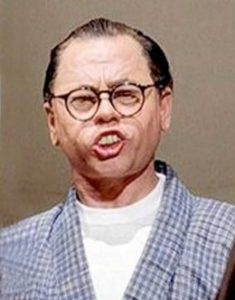

[8]Unsurprisingly, modern arbiters of virtue don’t like Breakfast at Tiffany’s very much. It is obviously heteronormative, anti-feminist, and otherwise “problematic.” But their ire is focused mostly on Mickey Rooney’s portrayal of Holly’s upstairs neighbor, Mr. I. Y. Yunioshi, as a buck-toothed Jap buffoon, straight out of World War II propaganda cartoons. Frankly, even I am offended by Mr. Yunioshi. Capote’s novel makes much more of race, but it is hard to say if it is “problematic” or “woke.” For instance, Holly notes that José has a touch of black blood. But she doesn’t mind the prospect of having slightly “coony” babies as long as the father is rich and respected. (Eventually, they’ll come for Capote as well.)

[8]Unsurprisingly, modern arbiters of virtue don’t like Breakfast at Tiffany’s very much. It is obviously heteronormative, anti-feminist, and otherwise “problematic.” But their ire is focused mostly on Mickey Rooney’s portrayal of Holly’s upstairs neighbor, Mr. I. Y. Yunioshi, as a buck-toothed Jap buffoon, straight out of World War II propaganda cartoons. Frankly, even I am offended by Mr. Yunioshi. Capote’s novel makes much more of race, but it is hard to say if it is “problematic” or “woke.” For instance, Holly notes that José has a touch of black blood. But she doesn’t mind the prospect of having slightly “coony” babies as long as the father is rich and respected. (Eventually, they’ll come for Capote as well.)

I highly recommend Breakfast at Tiffany’s. But what is most enchanting about this film can’t be captured in prose. It simply must be seen—for the beautiful people, the iconic fashions (one of the little black dresses Audrey Hepburn wore in this film fetched nearly one million dollars at auction), and its portrayal of a glamorous, safe, overwhelmingly white New York City.

Watch it as nostalgic, escapist entertainment—a mid-century American time capsule. I’m betting you’ll want to re-watch it as a character study that even manages to have a “message”—and a wholesome one at that. It communicates the joys and follies of youth in America at its peak—an age of seemingly infinite potential—and the necessity of finally growing up and actually taking a stand, of actually being someone. It became the road less traveled.

Source: https://www.unz.com/tlynch/breakfast-at-tiffanys/ [10]