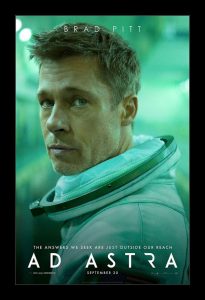

Ad Astra

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledAd Astra (2019), starring Brad Pitt and directed by James Gray, is the best science fiction movie since Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar (2014). Like Interstellar, Ad Astra is visually striking and emotionally powerful, stimulating to both thought and imagination, and unfolds at a leisurely pace—all traits inviting comparisons to Kubrick and Tarkovsky, although I hasten to add that I found both Ad Astra and Interstellar so absorbing that my attention never wavered.

Ad Astra is set sometime later in this century. The US has permanent bases on the Moon and Mars, but the farthest any manned missions have gone is Neptune, where the Lima Project was sent to scan the universe for signs of intelligent life outside the interference of the sun’s magnetic field. However, when the Lima Project went silent, sixteen years into its mission and thirteen years before the time of the film, the US ended deep space missions.

Brad Pitt plays astronaut Roy McBride, a Major in the US Space Command. Roy is the son of astronaut Clifford McBride, the Commander of the Lima Project (brilliantly played by Tommy Lee Jones). The film begins with Roy McBride working on a communication tower that extends from Earth into space. It is a modern tower of Babel. The tower is struck by a mysterious power surge, and Roy literally falls to Earth. Luckily, he is equipped with a parachute which allows him to land more-or-less safely. The whole sequence is as thrilling as it is bizarre.

It turns out that the power surge has affected the whole planet, leading to thousands of deaths. After recuperating in the hospital for a few days, Roy is called in to be debriefed and meets some top brass in Space Command (a white, a Latino, and a black woman—from intelligence, no less—for in diversity casting this film is as depressingly predictable as NASA).

It turns out that the surge was caused by an anti-matter discharge near Neptune. The Lima Project was powered by anti-matter. Space Command believes that Clifford McBride is alive and may be responsible for the surge, which if unstopped might destroy the Earth. They ask Roy to broadcast a message to his father from Space Command’s last secure communication hub on Mars. They hope he will respond, which will give Space Command a fix on his location, at which point they can dispatch someone to stop the surge by any means necessary.

The rest of the movie follows Roy from Earth to the Moon, from the Moon to Mars, and from Mars to Neptune—where he finds his father—then back home. This much is not a spoiler, since it can be gathered from the trailer—which is actually quite different than the final film. For one thing, Liv Tyler as Roy’s wife Eve was almost eliminated from the final cut. I don’t wish to give away any more of the plot, because I want you to see this film. But I do want to discuss some of the themes, which will require mentioning some details.

Ad Astra is interesting because it meditates on the personality traits necessary to explore and settle the cosmos. Clifford McBride left his ailing wife and thirteen-year-old son on a one-way mission to find intelligent life in the cosmos. What kind of people are capable of leaving their homes and saying goodbye to their family, friends, and neighbors—forever? Obviously, such people need to have weak ties to the people and places of their birth, or they would never be able to leave them.

Beyond that, they need to have some sort of mission to sustain them, a counter-weight to the things they left behind. In Ad Astra, Clifford McBride is portrayed as an intensely religious man. His faith is twofold: in God, the creator of the cosmos, and in the existence of intelligent extraterrestrial life, which is for many people a kind of religion as well. The four astronauts who take Roy McBride from the Moon to Mars are also intensely religious Christians. There is no sign that Roy McBride shares any of their beliefs. He seems like more of a secular Stoic.

Of course, weak roots and powerful senses of mission are the same traits possessed by past generations of explorers and settlers. Not even a century ago, when people departed on ships for new lands, they could be reasonably certain they would never be coming back. They knew how to say goodbye forever.

Ad Astra also confronts us with just how hard space exploration is on people. Clifford McBride chose to widow his wife and orphan his son to explore the cosmos. Roy chose to follow his father’s career, but he chose not to have children of his own, and his sense of mission destroyed his own marriage. (In a newsflash, Eve informs him that she is “her own person.”)

Many people, however, can’t really leave the Earth behind, so they replicate the best and worst of it wherever they go. Or they simply go a bit mad out in the void, sometimes to the point of mutiny. In one suspenseful and shocking sequence, we see that even the animals we bring into space can go mad and mutiny.

Ad Astra can be taken as an anti-religious film in two ways. First, Roy’s absent father out in space is very much analogous to the Biblical God. Roy can’t help loving the man who abandoned him, but in the end, he finds the strength to let him go. Second, Roy’s father is sustained by his faith in the existence of extra-terrestrial life, a faith to which he sacrificed first his family then his crew. But the Lima Project found no evidence of extraterrestrial life. Clifford begs his son to help him continue his quest. “You can’t let me fail.” But Roy responds, “But dad, you haven’t failed. Now we know, we’re all we’ve got.” It is an extremely touching scene, because as the movie shows, men like Roy McBride can do great things without faith in higher powers.

Since the same causes give rise to the same effects, it seems inevitable that the causes that gave rise of intelligent life on Earth will give rise to intelligent life elsewhere in the cosmos. Furthermore, given how big the universe is, it is likely that other intelligent life exists right now. Frankly, though, I find that a chilling thought, since if intelligent extraterrestrials arrived on Earth, the human race will be in the same position as primitive peoples around the globe when white explorers first arrived. We wouldn’t have a chance. I would much prefer to know that “We’re all we’ve got,” that—free of gods and aliens—our kind are free to expand unopposed into the universe.

Both Clifford and Roy McBride are magnificent portraits of Faustian European man. As Clifford tells his son, “Sometimes, the human will must overcome the impossible.” Roy does just that. He is a study in what I consider the real meaning of “cool.” He is the intelligent man of action, the taciturn, unflappable Nordic explorer. He has nerves of steel. He is “focused on the essential, to the exclusion of all else.” He has a slow pulse, which helps him stay cool in tight spots. (When a spaceship is in trouble and the captain is paralyzed, Roy coolly steps in and saves the day. Roy’s pulse only gets elevated when he hears that his father is really alive.)

If Roy is a Faustian hero, Clifford is a Faustian anti-hero, like Captain Ahab, whose indomitable will is twisted by an obsession, ultimately destroying him and everyone around him.

The most poignant thing Clifford says is, “We’re a dying breed, Roy.” No kidding. Roy McBride is the childless white Atlas on whose shoulders the whole world rides. He dutifully takes orders from affirmative action blacks and browns, wimpy man-buns and pushy dykes. He obediently shares his feelings with machines. They use him to get what they want, then shove him aside. When he sticks up for himself, Space Comm sends a black, an Oriental, and a gutless white to “neutralize” him, and they can’t even kill him without his help. Disavowed by his “superiors,” he saves the world on his own. When men like Roy McBride finally take the red pill, they will finish this system in short order. But don’t expect Jewish director James Gray to direct that epic.

Ad Astra isn’t a perfect movie. The script is highly intelligent, and I enjoyed the deliberate pace, but early on, I had the feeling that Gray was throwing arbitrary action sequences at us, just to keep people with short attention spans occupied. But even these sequences illustrated the larger themes of the film, such as the madness induced by losing one’s roots. I also found the music by Max Richter and Lorne Balfe to be undistinguished, although there is one beautiful theme that brings to mind Jerry Goldsmith’s Alien score. But by the time this movie gets to Mars, it is absolutely riveting, largely thanks to the magnetic performances of Brad Pitt and Tommy Lee Jones. Although Ad Astra doesn’t dazzle the eye with special effects and quick cuts, it is often simply beautiful to look at. But above all, Ad Astra is a feast for the mind. You’ll be thinking about this movie long after the final frames.

The Unz Review, January 21, 2020