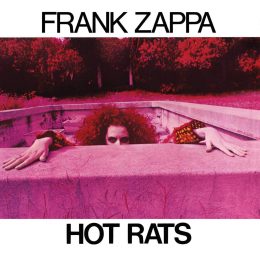

Frank Zappa’s Hot Rats

Posted By Scott Weisswald On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledOne of the first albums to be recorded on 16-track tape, Hot Rats spawned a jazz standard, a sprawling meditation on prostitution, and some of Captain Beefheart’s best vocal work outside of Trout Mask Replica. It’s mostly instrumental, but does not lack any substance, and the sounds it contains are both timeless and reflective of the late 1960s. The agelessness of this record can be attributed in no small part to the advances it brought to music more generally. Rats heavily featured processed audio, sonic trickery, and use of the recording studio as an instrument itself.

Hot Rats also sounds very different from much of Zappa’s earlier solo work and the recordings of The Mothers of Invention. There’s no satirical takes on American culture or sprinklings of musique concrète. Zappa, along with collaborators as diverse as the aforementioned Beefheart and French violinist Jean-Luc Ponty, decided to let their rich, colorful tunes speak for themselves. The lessons Zappa learned from his previous, less-than-friendly recordings were applied to remarkable effect on Hot Rats. This record is both a testament to Zappa’s credo, and also a reminder that pleasant, groundbreaking music requires an odd, experimental past.

The beginning of this album is the famed “Peaches En Regalia,” a bright tune now considered a modern jazz standard. It’s composed of buzzy organ, drums in double time, and an exuberant horn section that shreds through the dense soundscape created by processed bass and various woodwind instruments. “Peaches” has not a single moment of lamentation, but it never drifts into the dangerous territory of decadence. Much like the exuberance of discovering a new continent, medicine, or animal, Zappa and his band allow their excitement over new soundscapes to bubble over. As the cherry on top, Zappa solos on bass — tuned several octaves up.

“Willie the Pimp” begins with a bluesy riff and Captain Beefheart growling about the day in the life of a man peddling “hot rats,” or women of the night, on a street corner. Without a doubt, some of Zappa’s allure is the degree of exclusivity his music has. It’s certainly not due to its lack of accessibility; Zappa’s tunes, especially in this era, could have been appealing to a massive audience. Rather, by tossing gratuitous vulgarity (for the time period, at least) over the top of his work, Zappa helped prevent his music from becoming too popular. Those that listened were those not shocked by cheesy degeneracy, and were therefore capable of seeing his music for what it was. This afforded a level of creative freedom seldom observed during the era. A lack of pretentiousness also prevented his work from being resigned to the stuffy halls of the orchestra or jazz club, where his work likely would have been well-received, but more or less hidden from the view of a public that never patronized such venues. Groups tenuously described as “experimental” as the Beatles were still very concerned with how many records they could sell. Zappa just wanted to lay down some fresh licks. He did exactly that on “Willie the Pimp,” by the way, for about seven minutes.

“Son of Mr. Green Genes” is an interpolation of “Mr. Green Genes” from the Mothers of Invention album Uncle Meat. It’s about nine minutes long and built around a brass motif exuding with carefree life. “Son” also contains one of the more technically complicated solos on the album, with Zappa tenderly floating through multiple octaves on guitar. “Green Genes” is remarkable for its composition as well. It doesn’t seem too far away from what one would hear in a jam session of talented musicians, but multiple diversions from raw musicality highlight the value Zappa’s studio prowess adds to the song. Glimmering organs, drums that bounce around the ear in four-dimensional stereo, and the barely-perceptible flourishes that adorn the ends of notes like fringe on a flag create a fleshy and invigorating atmosphere that threatens to drown the listener at every turn.

“Little Umbrellas” contains the most straightforward jazz on the record. Syncopated drums give structure to the flowy entourage of instruments including keyboards and woodwind. At three minutes, eight seconds, “Little Umbrellas” stops itself short of becoming a bore. The modern touches it contains are little examples of how innovation in sound are born not of rejections of tradition, but by synthesis of new knowledge with the old. The late 60s was teeming with examples of this ethos, ranging from the industrial-folk sensibilities of King Crimson, another prog innovator, or the Velvet Underground. After all, an experiment is no experiment without a control.

“The Gumbo Variations” has the energy of a coursing river. Sound never ceases, but rather ebbs and flows with the soupy consistency of brass timbre and Zappa’s occasional electric interjections that ooze with a lackadaisical, almost comical unpredictability. None of these detours into harmonic squealing lack discipline, however, fitting perfectly into the neon-and-smoke-filled atmosphere of the jam’s texture. The importance of the jam becomes wholly apparent when Ian Underwood begins his equally bombastic tenor saxophone solo, a drunkenly chipper slide about every direction the laws of sound permit. For a complete gumbo, there’s also a lengthy pour of electric violin handled by Don “Sugarcane” Harris. “Gumbo,” despite its length, does not drag itself along for an unreasonable amount of time. There doesn’t seem to be a measure of solo from any of the band’s members that repeats itself more than twice, and the jam itself shows evidence of evolution throughout the track’s 12 minutes, 54 seconds. There’s even a drum break! To ask for any more elements would result in less of a gumbo, and more of a jambalaya.

“It Must Be A Camel” is the final track, and it may also be one of the earliest (and accidental) examples of the drumlines that would define genres such as breakcore techno and modern incarnations of metal. By overdubbing drums at varying speeds, a rapid-fire percussion effect was created, adding sources of nearly arhythmic tension to a song that would otherwise be a rather unremarkable, albeit funky, jazz session. The song also contains varied phases of tempo and dynamics, repeated quintuplets, and variations on scales that bounce up and down the staff with precision, but exuberance.

Hot Rats was not immensely popular, likely by design. It reached the position 173 on the 1969 Billboard chart, and was also the subject of label reissues and edits before Zappa left Warner Bros. in 1981. Like many invaluable and influential pieces of art, Hot Rats did not require the adoration of massive crowds for its ideas to take hold and shape the landscape of music both popular and underground. Rats is simply the shell that contained Zappa’s numerous strokes of genius; strokes that we can hear, if we listen closely, repeated in albums released to this very day. Influence alone is not the exclusive hallmark of great music, however. Hot Rats remains listenable in the current year, and its lush production means that an attentive listener can find a new piece of inspiration with every listen.

For those looking to do exactly that, Hot Rats was recently given a near-anthological reissue containing over 7 hours of takes [2] from Zappa and the band’s recording sessions in California. It’s a dissective, exhaustive collection that places Zappa and his collaborator’s creative chops on clear display; and most importantly, makes their innovation and influence all the more undeniable.