Pinocchio: The Face of Fascism

Posted By Margot Metroland On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledExtraordinary! There are three—maybe four—Pinocchio films now in development or newly released. They all promise to reveal dark, hitherto unexplored aspects of the famous marionette’s saga. One is a Robert Downey Jr. [2] project that’s been hemming and hawing since about 2012. Initially Downey was planning to play both Geppetto and the title role. Now he’s older, so he’ll just play Geppetto. A new live-action Pinocchio premiered last month in Italy. And even Disney [3] is now talking about making its own live-action remake of its classic animated feature.

A more promising production is Guillermo del Toro’s ambitious stop-motion feature, funded by Netflix [4] and slated for release next year. Supposedly this one will be set in Fascist Italy. As del Toro explained to the Hollywood Reporter [5],

“It’s not a Pinocchio for all the family,” he said of his story, set in 1930s Italy. So is it a political film? “Of course. Pinocchio during the rise of Mussolini, do the math. A puppet during the rise of fascism, yes, it is,” said the filmmaker.

Exactly how Il Duce fits into the plot is something left to our eager imaginations for now. (“Do the math” indeed!) Del Toro and co-director/animator Mark Gustafson have been very cagey about the plot. Most commentators are guessing it’s going to be an unsubtle slam at Right-wing-ism. As in, for example this breathless gush that appeared in Forbes [6]:

Del Toro has long wrestled with the legacy and horrors of fascism. His adaptation of Pinocchio, taking place in Italy with such horrors on the horizon, will surely be rich with similar packed meaning [sic]. And in our contemporary context of far-right authoritarian governments making considerable political gains throughout the world, we need rich narratives highlighting the evils of fascism, racism, hate, and other life-destroying dogmas.

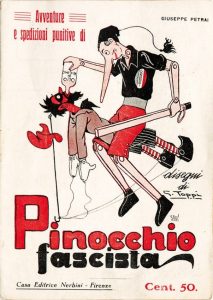

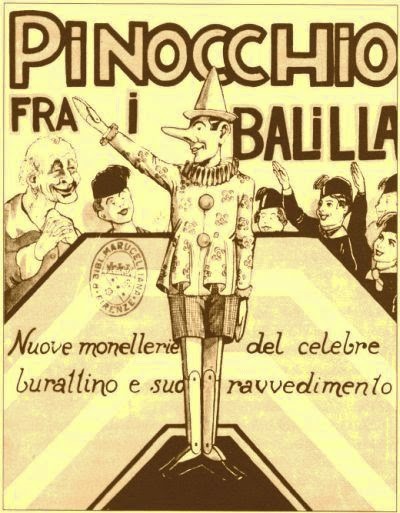

So we are to expect a misconceived, Leftist take on the Mussolini era, painting a black legend for a place and time about which most people know little and care less. But it does raise the question of why no one ever thought of this angle before. Because, funnily enough, there are certain connections between the famous puppet and the Mussolini years. In that era Italy published a run of juvenile books starring a Fascist Pinocchio. These depict him as a gallant, curious adventurer, a bit like Tintin: the very incarnation of Italian nationalism.[1]

Some of the tales are pretty amusing. In 1923 Pinocchio is fighting the Reds and dousing them with castor oil; in a 1927 tale he goes to the Fascisti cadet school, where he builds his character and sense of national destiny. In a couple of others from the 1930s he goes to Africa and tries to civilize the natives. Most surprisingly of all, in a 1944 book he encounters a friendly officer in the Waffen SS and offers to enlist. (Pinocchio is, after all, a woodenheaded North Italian.)

The Curse of Pinocchio

Political angles aside, the overriding mystery for me is why so many people today would want to do yet another Pinocchio movie. The original 1883 tale by C. Collodi is a convoluted, disjointed work to begin with. The title character, as written, is rather repellent. And Pinocchio films have never done well. The latest release, a live-action one with Roberto Benigni as Geppetto, opened in December 2019 to tepid reviews (“lacks a strong narrative thrust”—Variety [9]). Before that, there was one in 2002, this time with Benigni as the puppet. That film sank like a stone (“Cinematic cesspool…the film is awful. Incredibly bad,” says one online review [10].) Even the big Walt Disney version, completed in 1939, flopped on first release, and helped bring the Disney studio close to bankruptcy.

Looking ahead, I imagine del Toro’s Pinnochio-in-Mussolini-Land might have possibilities, if stop-motion is your thing (I rather liked Fantastic Mr. Fox, which Mark Gustafson also did). But somehow I can’t see crowds rushing to the multiplex to see ponderous live-action Pinocchios, whether they’re from Disney, Roberto Benigni or Robert Downey, Jr.

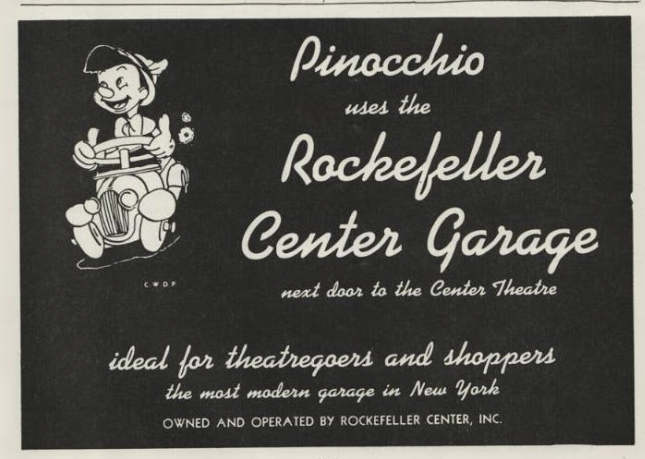

Here I must digress a bit about the Pinocchio most people think they know, but usually don’t: the Walt Disney version. As is so often the case with film scripts, it’s arguably superior to the source material, with a tighter, more straightforward narrative, and a far more sympathetic lead. It was eighty years ago (February 7, 1940, to be exact) that Disney’s Pinocchio premiered in New York’s Rockefeller Center. This should have a big splashy deal, like the sold-out run that Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs enjoyed when it opened at Radio City Music Hall in early 1938. But a few things went wrong. Disney missed the scheduled Christmas 1939 opening at Radio City because the film prints weren’t ready in time. So Pinocchio opened six weeks later at the Music Hall’s little-sister movie house down the street, the Center Theatre. The weather was good, but it was February, never a great movie month, and children weren’t on school holiday. Reviews of the film were glowing, but Pinocchio never became the must-see that Snow White had been.

All this hurt the bottom line. Pinocchio is still widely acclaimed as Disney’s finest animated feature, but the hard fact is that it lost half a million in its first release, out of a cost of $3.5m. (Snow White had cost $1.5m and grossed over four times that.) Later that year the studio released an even bigger dud, Fantasia. By year-end the studio found itself with no cash and no credit.

Walt Disney rescued his company with a string of simpler, lower-budget features (Dumbo, Bambi, and others), but there always seemed to be a kind of curse attached to Pinnochio, the film that didn’t meet its premiere date, and nearly sank Disney. The original book is indeed dark, tangled and frightening, but so is the film, even if the plot makes more sense. It’s scarier than Snow White, which famously made children wet their pants whenever the witch showed up. No happy dancing dwarfs in Pinocchio, or tweeting chickadees to offset the terror sequences; just an unrelenting series of kidnappings, imprisonments, whippings, transformations into donkeys; then an attempted drowning, and a swallowing by Monstro the Whale (in the book it’s a shark, three stories high). And the film might have been even darker. In the original sketches and storyboards, the artists hewed close to Collodi’s original concept: Pinocchio as sociopathic, dowel-nosed Frankenstein’s monster. Walt balked at this, so the studio cuted-up the character, giving him a shorter nose, an alpine hat, and generally a more big-eyed, lovable disposition.

[11]

[11]At least the Rockefeller Center Garage made money. (Ad from 1940 premiere program, via Disney History Institute.)

For the next few decades, while the Disney studio put out milder, upbeat animations, Pinocchio remained a legendary but rare item, shown only in limited engagements every eight to ten years. In fact, if you grew up between 1940 and 1990, you probably never saw Disney’s Pinocchio, other than in tiny snippets on television. You might have seen a lot of Jiminy Cricket on Disney TV shows, his Cliff Edwards tenor urging you to read the E-N-C-Y-C-L-O-P-E-D-I-A, or crooning along to Mickey Mouse’s piano in the perennial Christmas Special, “From All of Us to All of You.” And you saw Pinocchio lunchboxes, and Little Golden Books, and maybe jigsaw figures of Pinocchio, Geppetto, and Figaro the cat on the wall of your pediatrician’s office. What you probably didn’t see was the actual motion picture Pinocchio. I myself first saw it at age 16, when it was screened exactly once during a Disney retrospective at Lincoln Center.

I belabor all this because I have chafed, with annoying frequency, at glib remarks in movie and book reviews that say something like, “Of course most people”—or “most Americans”—“know the Pinocchio tale entirely through the Walt Disney film, which, though delightful, is very different from the book . . .” Et cetera. Quite obviously, most people could not know Pinocchio through the Disney cartoon, because most people never got to see it. Furthermore, the original tale has always been in American homes, almost invariably in illustrated editions showing the puppet much as he was in Collodi’s classic: an ungainly, stilt-legged, round-headed marionette in high, pointed, sugar-loaf hat. The whole reason Walt Disney selected this property for this next feature after Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is that Pinocchio was a story everyone already knew.

Animator Mark Gustafson has called the Disney version “saccharine,” and insists the book, like his forthcoming film, is much darker. The point is arguable. Certainly, mutilation and body-mods figure more graphically in the book. Pinocchio burns his legs off and Geppetto has to make him new ones. The begging, thieving Fox and Cat pretend to be lame and blind, respectively, early in the story; when they turn up again at the end they truly are paralytic and sightless. The Fox has even cut off his lush tail and sold it as a fly-swatter. Pinocchio’s delinquent friend Candlewick (Lampwick in the Disney film) remains a donkey forever and dies in a stable. Pinocchio even gets hanged in a tree and dies. This is because the author was sick of his character by this point and wanted to kill him off, much as Arthur Conan Doyle got rid of his famous detective by sending him over Reichenbach Falls. As with Sherlock Holmes, Pinocchio makes a comeback, though this makes for some weaselly explanations when the author revives the character.

Often enough, though, the Disney version is creepier than the book. Collodi’s story doesn’t show us Pinocchio and his bad companion drinking beer and smoking stogies in a pool hall, just before they start to bray and turn into donkeys. Collodi doesn’t tell us much about the wayward boys’ degeneration: they have five months of lazy indulgence and no school, and then one morning they sprout donkey ears. With Disney the transformation seems to happen in a single night. And Disney’s Pleasure Island is far better realized than the book’s sketchily described Toyland. When Lampwick and Pinocchio get to Pleasure Island, it’s like the opening scenes of Blade Runner, a cacophonous Nighttown of talking billboards and violent fights. The whole boy-to-donkey industry is more sinister in Disney, with the roundup of the lads frankly presented as mass kidnapping for profit. One of Disney’s embellishments is a frightened little donkey-boy, still dressed in middy blouse and sailor cap, who says his name is Alexander and he wants to go home to his mama. (“Take ‘im back! ’E can still talk!” shouts the coachman, as donkey-boy gets kicked back into a holding pen.)

The Gradgrind Republic

Pinocchio’s creator, Carlo Lorenzini aka Collodi, did not write the Fascist storybooks I mentioned above, for the very good reason that he died in 1890. Following the original Pinocchio story, the puppet became a kind of stock, public-domain character who figured in dozens of storybooks by many authors. So it wasn’t surprising for Pinocchio to get repurposed with Fascist themes, beginning in the early 1920s.

But if you look hard and use some imagination, you can detect a background of proto-Fascism in the original tale. By this I don’t mean regimentation or militarism or goose-stepping, or any of the other Red Front caricatures of Fascistry. I mean rather the picture of a secular, rather bourgeois, quasi-republic known as the Kingdom of Italy: the foundation that Mussolini eventually built his own secular, bourgeois, corporatist state upon. Both Italys were ultimately the product of the Italian Risorgimento, the wars of Italian independence and unification in the 1840s-60s.

Collodi himself had been a volunteer soldier in Tuscany, and so was very much a man of the Risorgimento. When he began Pinocchio in 1880, he was in his fifties, and had had a varied career as a seminarian, political journalist and translator. It had been less than twenty years since “Italy” was first created from a hodgepodge of old dukedoms and principalities. Only a decade had passed since the new Kingdom appropriated the last rump of the Papal States, and chased Pius IX out of the Quirinal Palace and into self-imposed imprisonment in the Vatican, from whence he forbade Italian Catholics from voting in elections in the new anti-clerical, Masonic republic. (Most obeyed.) In Collodi’s time, Italy was still an artificial country without a clear identity or sense of usable past beyond the recent wars of unification. This would change in the next decade or two, as Italy saw the flowering of nationalism and anti-parliamentarianism in literature and politics (Gabriele D’Annunzio and Gaetano Mosca are two prominent names here). Meanwhile there was an expansionist lust for foreign adventures and the acquisition of colonies that—as with contemporary France and Germany—were of doubtful value. This arc of nationalism, expansionism, and suspicion of democracy is the cultural nexus between the rather sterile, bourgeois, secular land of Pinocchio’s time and that of the Fascist era.

As fantasy yarns go, the Pinocchio story is an odd duck. There are no knights or princesses or wizards. There’s little magic at all, other than the basic premise of an animated wooden puppet. Collodi was no stranger to fairy tales (he translated Charles Perrault’s stories from the French) yet very few of the common fairy-tale conventions found their way into Pinocchio. We have talking animals, but they are merely stand-ins for human varmints. Lazy boys turn into donkeys, but only because in the author’s opinion that is figuratively true. A magical Little Girl with Blue Hair intrudes about two-fifths of the way into the book, and she is said to be a Fairy; but she is neither a convenient proxy for the Blessed Mother (as often supposed), nor an angel, nor part of the story’s original imaginative scheme. She enters as merely a dea ex machina, brought in to bring Pinocchio back to life after his false friends hang him.

Likewise the setting is neither a fantastic kingdom nor a land of witches and ogres and seven-league boots, but rather an everyday, “modern” European land stuffed with middle-class industry and aspirations. There is no discernible class hierarchy. Even though Italy itself had a king (whom Collodi didn’t much care for), no king is mentioned in this story. Nor are there any castles or monasteries, or nobles, priests or religious orders. In Pinocchio, nobody goes to church, nobody prays. In fact, there is no religion at all, other than the suggestion of a tree-worshiping paganism (the lumber that Pinocchio is cut out of is already talking before Geppetto makes the puppet), and a belief in forest-dwelling little people who are actually fairies.

For that matter, there’s no high culture to speak of. This is an Italy of workshops and the counting house, where grand opera and classical music are unknown. Collodi’s system has no room for transcendent contemplation or artistic excellence. A real-life Geppetto would probably have a pianoforte in the parlor—a squeeze-box, at least. But this one doesn’t, not in Collodi’s world. When we see entertainment in Pinocchio-land, it is of a very low order: a carnival with a fire-eater and a puppet show. And then there’s Toyland, which stands for every layabout retreat where parasite-people graze, contributing nothing to society. Collodi is positively Marxian in his rejection of high culture. For the working class and petite bourgeoisie, it’s an attractive nuisance.

But, like Mr. Gradgrind in Dickens’s Hard Times, Collodi does cherish a simplistic notion of education. Education, he believes, is a necessity, the key to worldly success. What he has in mind here is free, secular, practical education. (If he were alive today, he’d probably be prating about “STEM.”) Of course, many people don’t wish to be educated, or they shun school because it seems newfangled and unnecessary. And this is a social problem very much at the front of the storyteller’s mind. Children who slack off and don’t study become donkeys; there’s no place in the modern world for the unlettered, other than becoming beasts of burden.

Unproductive hangers-on are another social problem we see in Collodi’s Pinocchio. The towns are infested with beggars, swindlers, and get-rich-quick sharpies, all combined here in the Fox and the Cat. When our puppet-hero comes into some gold coins, the Fox and the Cat repeatedly attempt to steal them, finally persuading him that if he plants his gold pieces in a special Field of Miracles, each will sprout into a tree of gold! Collodi would say this is precisely the sort of foolishness that the poor and uneducated are prey to.

Good Neighbor Pinocchio

Collodi published the Pinocchio tale as a serial in a juvenile newspaper. At the time it would have been recognized as entertainment in a standard genre: the instructional tale for children. The arch-example of this mode was Heinrich Hoffmann’s Struwwelpeter (1845). Here, the author shows you a nasty, misbehaving child who sucks his thumb or won’t eat his soup, and tells you what ill tidings befall the miscreant. (A tailor comes in and cuts off the child’s thumbs; Augustus who won’t eat his soup just wastes away and dies.) Another distinctive characteristic of the genre is that it is almost always set among the urban middle class, not peasants or aristocrats; and this is likewise the case with Pinocchio.

This cautionary genre had pretty much died out by the early 1900s when Mr. Hilaire Belloc, MP, parodied it in a book of doggerel (Cautionary Tales for Children, 1907 [2]) in which children come to painful ends for doing pretty much nothing out of the ordinary. For example: “The chief defect of Henry King/ Was eating little bits of string.” Henry King dies in agony, with the finest physicians in attendance. A great irony here is that the original genre is long forgotten except by literary historians, while Belloc’s parody attitude lives on and on, notably in the work of Roald Dahl, Edward Gorey, and maybe Lemony Snicket.

Collodi himself slipped into parody when he began Pinocchio. He made the puppet a wicked and thoroughly despicable character. As soon as Geppetto carves him out of a talking log, Pinocchio starts mocking his poor “father.” He kicks him, and steals his yellow wig. Shortly afterwards, he smashes a 100-year-old Talking Cricket with a mallet, when the cricket tries to lecture him about disobedient boys. (The cricket would become gloriously exalted in the Disney version.) Pinocchio sells the schoolbook that Geppetto pawned his overcoat to buy, and plays hooky at a visiting puppet show.

Collodi detested Pinocchio, and soon killed him off. When he was eventually pressured to bring the puppet back, the story improved immensely. It ran off onto imaginative, unlikely tangents that were far superior to the tiresome early part of the book, where we are repeatedly hit over the head with Pinocchio’s cruel nature and irresponsibility. It’s in this post-comeback phase that Pinocchio goes to jail, lives in a doghouse, is abducted to Toyland, becomes a trick circus donkey, gets swallowed a vast shark, and finally matures into a pleasant hero and loyal caretaker of father Geppetto.[3]

Thus, after coming back from the dead, Pinocchio evolves into a good-natured, educable chap, nearly as anodyne as Mickey Mouse. And that was the generic Pinocchio later generations were left with, in the many post-Collodi Pinocchio tales. By the time Mussolini came along, it was easy to adapt the puppet to all sorts of Fascist-themed stories, because Pinocchio’s original wickedness was long forgotten, and he was little more than an internationally recognized literary symbol of Italy. When Pinocchio visits Africa in 1930 (in a short novel called Pinocchio fra i selvaggi) he is greeted by a Western traveler: “I saw your portrait the other day in a bookshop window, in Canada!”

On the 1930 African trip, Pinocchio is on a mission to civilize, and teaches the natives some Western ways, e.g., how to use cutlery. In a later story set in Abyssinia in 1935 (Pinocchio istruttore del Negus), his attitude is more wary toward both the African natives and other Westerners. The Abyssinians seem diabolical, barely human, and reinforce Pinocchio’s awareness of his superiority. A caricatured English gentleman appears, in plus-fours and Austin Powers teeth, and Pinocchio feels contempt for this upper-class twit because the Englishman isn’t bothered by the natives’ backwardness and lack of hygiene.[4] A touch of the original Pinocchio’s brattiness remains (he kicks the Abyssinian leader, the Negus, in the face), but it’s all good-natured fun, and ultimately in the service of nationalist pride.

For an historian (whether of modern history or art) the most curious incarnation of the puppet might be the 1944 one where we’re in the Salò Republic and Pinocchio tells the friendly Waffen SS officer he wants to join up and see some action. The evil Fox and Cat are anti-Fascist partisans, and attempt to cajole Pinocchio into welcoming the Allied advance and fighting the Germans. In the end, Pinocchio rejects the Fox and Cat’s entreaties and flies off to battle, borne on the wings of a dove that the Blue Fairy has thoughtfully provided. And the illustrations are remarkably “modern,” done in a faux-naïf style that is a foretaste of the high stylization that would be seen in avant-garde animation and book illustrations of the 1950s.[5]

In the end, it seems, everyone can have his own personal Pinocchio, even when staggering around in blissful ignorance of what the original tale (or even the Disney version) is like. I am reminded of an early Leave It to Beaver episode in which Beaver’s mother, June, doesn’t want Beaver to see a trashy horror movie called Voodoo Curse. She tells him to go see Pinocchio instead, because she thinks it’s safer. Beaver is highly impressionable and prone to nightmares. June imagines that Pinocchio is playing at a local cinema, but that’s impossible. It’s 1958, and Pinocchio won’t be having its next re-release for another four years. Anyway, very much in the manner of Pinocchio being led astray by the Fox and Cat, Beaver goes with brother Wally and Eddie Haskell to see Voodoo Curse. He tells his parents they saw Pinocchio, but he’s soon rumbled, because he can’t describe any of Pinocchio’s “adventures.” So Beaver and Wally get sent to their room for being disobedient and lying about it. In the bedroom, Beaver fashions a Raggedy Andy into a voodoo doll of Eddie Haskell, who (we subsequently learn) becomes deathly ill.

The episode is full of ironies and script bloopers. June Cleaver pretends to have seen Pinocchio years ago, but of course she didn’t, or she’d know it’s nightmare fodder. Far scarier than Voodoo Curse, in fact, from what we see of the latter. It’s improbable that Wally and Beaver have never been exposed to any form of the Pinocchio tale; surely, when their mother asks, they would be able to improvise some notion of what happens in the film. And though we see a newspaper ad and theater posters for Voodoo Curse, we see nothing for Pinocchio. Beaver’s parents don’t even check to see if it’s playing anywhere.

Of course these are probably just scripting errors by inattentive writers. But it’s the same kind of inattention we see when reading portentous pronouncements about forthcoming Pinocchio movies. “Oh, our Pinocchio is going to be serious, it’s going to be grown-up, it’s going to be dark and terrifying—it’s going to have Fascism! Ooooh!” What it all tells us is that they don’t really know much about the material.

Notes

[1] Caterina Sinibaldi, “Pinocchio, a Political Puppet: the Fascist Adventures of Collodi’s Novel,” Italian Studies, 66:3 (London: Society for Italian Studies), 2011.

[2] Republished many times, notably in the Belloc anthology Cautionary Verses (New York: Alfred A. Knopf), 1962.

[3] The same imaginative flowering happened to Conan Doyle when he revived Sherlock Holmes after some years, beginning with The Hound of the Baskervilles (1901-02). Two-thirds of the total Sherlock Holmes corpus was written after Doyle resuscitated Sherlock, though the stories increasingly leaned toward espionage thrillers and “caper” plots involving stolen jewels, so that many Holmes aficionados do not consider them quite canonical. A similar parallel can be found with Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which Mark Twain began as a diversion on his “Type Writer” contraption, still a novelty in the mid-1870s. Twain didn’t know where to take it after Huck escaped his drunken, abusive Pap, and started down the river. When Twain finally picked it up again after six or seven years, he threw out any attempt at plot and just wrote the funniest stuff of his career.

[4] Sinibaldi, “Pinnochio, a Political Puppet.”

[5] Giovanni Tiso, “Making a Real Fascist Puppet,” Overland Journal, 1 May 2014. (Online here [12].)