Grimes’ Miss Anthropocene

Posted By Scott Weisswald On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,683 words

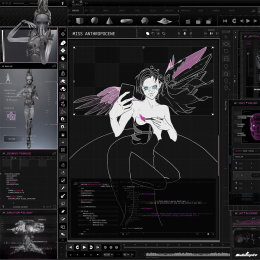

Miss Anthropocene is the fifth full-length release of Canadian avant-pop songstress Claire Boucher, known professionally as Grimes, and it’s considerably darker than much of her previous work. This is fitting — Grimes has stated that the concept of Miss Anthropocene, a triple-entendre, is that of an “anthropomorphic goddess of climate change. [1]” If this sounds like a bunch of woo nonsense to you, you’d be (mostly) correct. Grimes is well-known for her strange music, aesthetics, and personality. Her mainstream breakthrough was with Visions, an album she composed during a several-week-long bender where she deprived herself of natural light, sleep, food, and water, all while taking copious amounts of amphetamines. Visions ended up being a strong contender for some of the best musical output in human history. Whether that was on account of the psychosis or her raw talent is up for debate. I definitely encourage everyone to give it a listen, regardless, both because it’s a remarkable work itself and serves as a useful barometer for evaluating Boucher’s later output.

To put it more simply, the music of Grimes is far from straightforward. Boucher as a person isn’t easy to understand, either. She may be better known to Counter-Currents readers as the singer dating — and pregnant with the child of — Elon Musk, the eccentric tech billionaire and Twitter troll. Boucher’s musical output took a sharp turn after the two began seeing each other; her once bubblegum-like compositions became pounding, gnashing, industrial-influenced stompers about artificial intelligence gone rogue. This direction is reflected on Miss Anthropocene, and it’s to mixed results; on some tracks, the apocalypse seems imminent and Grimes is a violent angel urging you to either run away or observe the calamity. On others, you simply feel like you’re about to nod off at a party blasting MySpace music. Miss Anthropocene comes 5 years after her previous effort, Art Angels, and the work it contains suggests that Boucher’s sustained fame — whether it’s because of Musk or not — led to overproduction, uninspired songwriting, or just plain laziness.

The opening track “So Heavy I Fell Through The Earth” is a woozy, bass-heavy meditation similar to the ambient-focused house popular in the early 2000s, like Orbital. Grimes doesn’t betray her signature style for vocals on this track, though they’re a bit more washed-out than previous works: By layering dozens of vocal tracks on top of each other and carefully manipulating the dry and wet channels of the reverb on each track, the final product is a highly ethereal, angelic choir of one voice that can be experimented with endlessly. This vocal effect, fluttering synthesizers, thick bass, and a rolling trap-influenced beat create an atmosphere of aimless drifting, as if one’s been cast off into deep space aboard a powerless capsule. It ends with sustained choral ambiance and light garnishes of a twittering synthesizer in the musical equivalent of an LSD comedown. “So Heavy” begins the album on a high note.

“Darkseid” has an entirely different mood. Sharp delays, aggressive hi-hats, and indecipherable, frenetic Chinese rapping from feature guest 潘PAN — better known as Aristophanes, a frequent collaborator — pair excellently with modulated cowbell sounds and glaring string synths to create a foreboding wall of sound. “Darkseid” sounds as if it were pulled directly from the soundtrack to some terrifying cyberpunk dystopia, which seems to be exactly what Grimes intended for much of this record. This trope is only exciting for a while, however, and can grow stale or diluted if approached without laser focus.

“Delete Forever” follows. The title itself warrants discussion. In the Information Age, it’s implicitly understood that anything you upload to the Internet will remain there for eternity, existing in the form of caches, backups, archives, reuploads, screenshots, and traffic logs. Even content that you don’t intentionally upload to the Internet is at risk of compromise by lost devices, stolen hard drives, spyware, or Internet-of-Things connectivity run amok. We’ve more or less abandoned the premise of permanently erasing anything in our daily lives; even the things we don’t want to document may be saved by others and come back to haunt us later. This loss of privacy — or perhaps, autonomy — is reflected in the somber nature of this track. It’s mostly acoustic guitar and Grimes’ lightly-processed vocals in the beginning, later joined by puncturing percussion and sub-bass. “Delete Forever” walks a fine line between sheer depression and delusional optimism, which is likely the same thing one feels toying with the notion that they could delete something — or perhaps, themselves — for eternity.

Next up is “Violence,” one of the album’s leading singles. Grimes is joined by i_o on this song for a pulsing, nu-disco-inspired track awash in Grimes’ impressive display of vocal range. Grimes’ work has always been typified by the synthesis of disparate musical styles and lyrical content, and “Violence” is no different. The progressive house gesticulations of “Violence” are strange bedfellows with the pseudo-masochistic repetitions of Grimes, but the whole spectacle simply works. “Violence” is the cut of choice for a bunch of depressed dancers.

“4ÆM” has the energy of an old-school club tune, complete with break rhythm and synthwave melodies, periodically split up by diversions into vocal theatrics — “nananana” — or sublime, watery tempo changes. By this point in the album, it’s clear that the defining features of each track tend to be how they digress from a formula they establish for themselves in the beginning, and not necessarily because of any novelty or innovation they possess in composition. Anthropocene seems to either be a wall of electronic sound or a spacey foray into psychedelia better explored by artists, including Grimes herself, several years ago. Referring to the patterns and methods that defined dance music in the past may be suitable if your intent is to deconstruct or interpolate them with something new, but it’s not enough to simply sing strangely atop them.

This lack of innovation is also apparent on “New Gods,” a highly atmospheric track featuring intense reverb, a simple drum line for tension towards its conclusion, and Grimes’ typical high-pitched theatrics. “New Gods” might have been appropriate as an interlude were it not so long; it could easily have been half its length and been an appropriate breather from the drill-like aggression that defines most of the album. This isn’t the case, and “New Gods” seems to be material ripe for the “skip” button when listening to this album.

“My Name is Dark” has the distinct feeling of being appropriate for the closing credits of an anime series. [1] [2] It’s somewhat melancholy, it has fake guitars, an explosive chorus, and a very simplistic drumline. One gets the impression that Grimes was told she could take any style of music, apply her vocal technique and compressed noise to it, and then release it to great fanfare. “My Name is Dark” is also the number one suspect when it comes to Grimes’ apparently new tendency to overproduce; there is simply too much going on, yet too little interesting going on, for this song to be any good.

“You’ll miss me when I’m not around” is the shortest track on the album, which is a blessing of sorts. It sounds like a typical hyperpop song in the tradition of women like Charli XCX, except if the whole affair were played out loud inside of a church and then re-recorded from the rafters. Grimes seems to be chasing her own shadow. Few artists in the mainstream were recording music as odd as she was in the first half of the 2010s, which meant that she was the inspiration for countless other female-led acts to start taking greater creative risks. This culture has more or less fully matured in 2020, and the music of Grimes seems to be more influenced by her contemporaries than it was previously, causing her sound to feel (poorly) imitative of what she once was.

“Before the fever” is a track with a remarkable lack of direction. It drifts — yet again, drowned in reverb — from a highly tense, albeit drowsy introduction into what seems like the prelude to a dark, club stomper, but then transitions to an overblown and syncopated climax that lasts all of about 50 seconds before withering into an echoed, ambient outro.

“IDORU,” the final and lengthiest track at 7 minutes, 12 seconds, is begun with birdsong and the thumping of heartbeat-like drums that break into a quiet backdrop to one of the least interesting melodies in the world. “IDORU” doesn’t change much for most of its length, and Grimes vocals add more obnoxiousness than they do creative texture to the track. The ethos that seemed to guide this album’s production condenses quite nicely on “IDORU;” half-baked attempts at subverting pop music’s forms fall flat on account of their trite and unambitious nature. “IDORU” has likely been played in some form hundreds of times by failed bedroom pop outfits across the globe. The reason we’re hearing this rendition now? Grimes can rest on her laurels.

Miss Anthropocene is a good example of how artwork can collapse under its own pretentiousness. It contains no fresh sounds or insight, instead clinging to techniques used in the past in places where they’re inappropriate. Anthropocene also lacks the same sense of urgency that Boucher’s previous work has, despite its subject matter arguably being of greater relevance. In many ways, the stated themes of ecological disaster, technological hegemony, and societal collapse are simply too nebulous or ill-defined for this album to have even stood a chance. Anthropocene is more Tesla office elevator music than it is apocalyptic opera. Perhaps being shacked up with the man driving the very changes your concept album addresses dulls one’s artistic knife.

Given her pregnancy, it would make sense for Grimes to begin retiring from the spotlight. She left an undeniable mark on the music world in 2012, and it would be a shame for her art to turn into a dead, beaten horse.

Notes

[1] [3] More specifically, “Dark” sounds like what would happen if you applied an obscene amount of reverb to Lithium Flower, the credits theme [4] to Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex, and then handed the mix to a drunken man with a Moog.