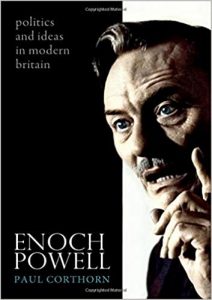

Paul Corthorn’s Enoch Powell: Politics & Ideas in Modern Britain

Posted By Margot Metroland On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,703 words

Paul Corthorn

Enoch Powell: Politics and Ideas in Modern Britain

London: Oxford University Press, 2019

Before reading this new biography of Enoch Powell (1912-1998), I’d expected it would be a rollicking Roy Jenkins kind of Parliamentary biography, full of witty asides in the smoking room and dark mutterings through the Octagon. Actually, it’s a detailed, often dry, but generally surprising survey of a political career.

It should be subtitled The Great Unknown. I was aware Powell had been an effective behind-the-scenes crafter of policy for the Conservative Party (and its Ulster Unionist affiliate, for which Powell stood in the 1970s and 80s), but before reading Corthorn I hadn’t realized how serious and influential a politician he really was. “Influence without power” is how Margaret Thatcher described his stature.

Powell had blotted his copybook with his so-called “Rivers of Blood” speech in Birmingham on April 20, 1968, in which he denounced nonwhite immigration to Great Britain. This had the effect of making him a virtual non-person, in terms of public profile and newspaper coverage, even though he was an MP for nearly another twenty years. But because he was out of the limelight, he was now able to perform as a Parliamentary eminence grise, shaping opinion to an extent that is seldom appreciated.

To begin with, you could call Enoch Powell the godfather of Brexit. As far back as the 1970s, Powell was warning about the dangers of Britain’s membership in the European Economic Community (now EU). In fact, as soon as Britain joined, Powell was speaking at rallies to Get Britain Out. His opposition to the EEC was not trade-based or protectionist. It was a matter of national sovereignty: a foreign entity that sets the rules for your agriculture and manufacturing, and forces you to use French weights and measures, will soon be writing your laws. This was obvious to the far-sighted Powell, but to press and politicians, it all sounded like cloud-cuckoo-land stuff.

Powell found allies not only among fellow Conservatives but also in the strongly nationalistic wing of the Labour Party. Incredible as it is to contemplate, in 1975 Labour passed a referendum to leave the EEC. This was right after Britain joined the Community. Powell’s warm feelings toward Labour were much like those of the arch-Tory minister and diarist Alan Clark, who “got on well” with Labour MPs. Clark liked to say he’d much prefer a patriotic British socialist government, versus a globalist Tory one. What Powell didn’t like were the pro-European Lefties — Roy Jenkins, Shirley Williams, David Owen, et al. — who broke away from Labour in 1982 to form the Social Democratic Party.

When UKIP was first founded in 1991 as the Anti-Federalist League party, its sole mission was to get Britain out of the EEC. This looked like a most quixotic venture in those days, but ex-MP Mr. Powell was right on hand to endorse its candidates — at least those he approved of. (He chose not to endorse Nigel Farage when Farage sought his backing in 1993. Corthorn doesn’t say why.)

The ironies are endless in Powell’s career. An Englishman from Warwickshire, he spent the latter part of his political career (1974-87) representing a South Down constituency in Ireland. He hated the United States and was disgusted by Britain’s role as lapdog in the 40-year Cold War with the Soviet Union, but his foreign-policy outlook was scarcely different from that of the American or British governments. He may have been a sort of Third Way man, but he certainly didn’t plump for nuclear disarmament.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s Truth, Justice, & a Nice White Country here [1]

Powell had permitted the importation of nonwhite Commonwealth immigrants to staff the NHS when he was Health Minister in the early 1960s, a scant few years before he raised the alarm about what nonwhite foreigners were doing to the country. To be fair, Powell did not directly encourage “coloureds” to come and settle in Britain, as is sometimes alleged. Rather, he permitted the NHS to hire from abroad, on a temporary basis.

It was partly because of his popularity, or notoriety, that the Conservatives swept the 1970 general election. This meant the new premier was Edward Heath (who had sacked Powell from the Shadow Cabinet after “Rivers of Blood”). Heath finally succeeded in his decade-long goal of getting Britain into the European customs union — the very thing that Powell would spend the remainder of his parliamentary years railing against. Powell supported Margaret Thatcher for Conservative party leader and then PM in 1979, while she idolized and was “mesmerized by” Powell; however, he had little respect for her ability or integrity. He expected her to renege on her promises to pull out of the EEC. And of course, he was right.

It’s unlikely that most people reading this — most Americans, anyway — would know who Enoch Powell was if it were not for that speech he gave in his hometown of Birmingham, on that famous 20 April 1968. Although it’s called the “Rivers of Blood” speech (because it concludes with a Sibyl prophecy in the Aeneid: “I see the River Tiber foaming with much blood”), the oration is not really as gory or apocalyptic as that suggests. It is fairly sedate, and it had a practical political context. Mr. Powell, MP, was campaigning against the new Race Relations Bill — the first of many! — that was being pushed by Home Secretary Roy Jenkins (“Our Woy” again, as Private Eye would say).

Powell saw danger ahead. He read a letter about an old widow pensioner in Wolverhampton, and this tale is the really incendiary part of the speech, the thing that got Powell on the front pages and made him the most popular man in Britain. I will condense it into a few sentences:

“Eight years ago in a respectable street in Wolverhampton, a house was sold to a negro. Now only one white (a woman old-age pensioner) lives there. . . She lost her husband and both her sons in the war. So she turned her seven-roomed house, her only asset, into a boarding house. She worked hard and did well. . . Then the immigrants moved in. . . The quiet street became a place of noise and confusion. Regretfully, her white tenants moved out. The day after the last one left, she was awakened at 7 a.m. by two negroes who wanted to use her phone to contact their employer. When she refused. . . she was abused and feared she would have been attacked but for the chain on her door. . . Immigrant families have tried to rent rooms in her house, but she always refused. Her little store of money went, and after paying her rates, she has less than £2 per week. She went to apply for a rate reduction and was seen by a young girl, who on hearing she had a seven-roomed house, suggested she should let part of it. When she said the only people she could get were negroes, the girl said “racial prejudice won’t get you anywhere in this country.” So she went home. . . She is becoming afraid to go out. Windows are broken. She finds excreta pushed through her letterbox. When she goes to the shops, she is followed by children, charming, wide-grinning piccaninnies. They cannot speak English, but one word they know. ‘Racialist’, they chant. When the new Race Relations Bill is passed, this woman is convinced she will go to prison.”

This woman is convinced she will go to prison. Forty years after Powell’s speech, a beaverish researcher at BBC’s Radio 4 said he’d discovered the identity [2] of this old lady in Wolverhampton. He said the story was full of holes. For one thing, the “excreta” through the letterbox didn’t actually happen to this old lady, it happened to her neighbor. Also, the old lady drank a lot, and had been “sectioned” a few times (i.e., forcibly committed to a public insane asylum). Nevertheless, the drunken crazy lady got on well with her “West Indian” (Jamaican) neighbors and sometimes babysat for them. They even sent flowers to her funeral!

You can decide for yourselves which story is the more credible: the letter-writer’s one from 1968, or the 2008 version from the Radio 4 guy. Both may be composites, both may be a pack of lies, but the first has an immediacy to it, along with specificity of details. The second looks like the kind of made-up smear you’d get from a sleazy lawyer or political flack. (“Aw, she was crazy and drunk. But we let her babysit!”)

Anyway, this was the inflammatory part of the speech. It was in all the papers, and the dockworkers in London came out to cheer Mr. Powell, MP, when he was next in town. If there had been a general election that year, it is claimed, the people of Britain would have made him Prime Minister.

The Powell speech is an American story, too. I can remember reading in-depth features on it in the New York Times and elsewhere. I was still a kid, but it was painfully embarrassing to read how Powell pointed to the United States as an example of race relations gone wrong — what Britain’s future would be if it didn’t reclaim its identity and get back on the strait and narrow — because negro race riots were a common occurrence in the USA. Every big city, every summer, seemed to have them. For the rest of the world, this was what America was about. How humiliating.

But then Enoch Powell disappeared from the headlines. In Britain, in America. Somehow or other, a new domestic crisis was ginned up to make the British forget about Jamaican piccaninnies harassing you in the street and shoving feces through your letter-slot. That crisis was described as the “civil-rights protests” or “Troubles” in Northern Ireland, a thirty-year-long guerrilla war of unfathomable causes, a conflict that never had any clear resolution, although it wound down because people eventually tired of it.

And that, I submit, is what really took the wisdom of Enoch Powell off the front pages.

Please support our work by sending us a credit card donation through Entropy [3] — just click “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All paid chats will be read and commented upon in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.