The Infamous Crash

Posted By Robert Hampton On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,409 words

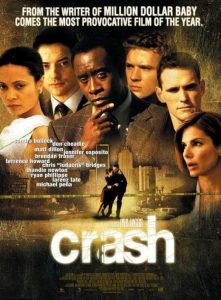

The gay romance Brokeback Mountain was predicted to win Best Picture at the 2006 Oscars. Instead, the independent ensemble Crash won; Brokeback was allegedly too gay for the Oscars.

Critics have never gotten over the result. Crash is regularly considered the worst Oscar winner ever and the chattering class has turned the film into a punchline. Ta-Nehisi Coates, the doyen of proper liberal thinking, declared Crash the worst movie of the 2000s [1].

It’s no mystery why: Crash surprisingly upholds a middle-class white view of race. You wouldn’t say it’s reactionary, but it’s not exactly progressive. Overt bigotry is deplored, but is understood to be caused by more than sheer irrational hatred. Stereotypes of non-whites are justified, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t good people. Race makes politics more concerned with pleasing interest groups and less so with proper governance. Crash is ham-fisted in its treatment of race and nearly every scene is too on-the-nose. But this is not why the film is so despised. It’s because it inadvertently justifies impolite racial attitudes.

“If you’re angry about race, but not particularly interested in understanding why, you probably like Crash. If you’re black and believe in the curative qualities of yet another ‘dialogue around race,’ you probably liked Crash. If you’re white and voted for Barack Obama strictly because he was black, you probably liked Crash. If you’ve ever used the term ‘post-racial’ or ‘post-black’ in a serious conversation, without a hint of irony, you probably liked Crash,” Coates wrote in his angry assessment of the film.

The film weaves the stories of roughly a dozen Los Angelenos whose lives crash into one another. Its star-studded ensemble includes Sandra Bullock, Brendan Fraser, Don Cheadle, Matt Dillon, and the rapper Ludacris. Los Angeles’ diversity is on full display with black, Hispanic, Persian, and Chinese characters. The film follows roughly a dozen characters as they struggle with racial conflict. Sandra Bullock plays a Karen [2] who can’t handle being carjacked by blacks and relying on Hispanics to do her housework. She’s married to the Los Angeles District Attorney, the hilariously WASP-named Rick Cabot (Brendan Fraser). A Rick Cabot holding a powerful position in 2004 LA is a bit too anachronistic. Cabot is worried that being carjacked by blacks will hurt him with minority voters, making him eager to please the black community in any way he can. Ludacris and Larenz Tate play the black carjackers.

Don Cheadle plays a rising black detective who is investigating a suspicious shootout between two cops. Cheadle’s character is also looking for his estranged brother, who turns out to be one of the carjackers. Matt Dillon plays a racist cop, Sgt. John Ryan, who struggles to take care of his ailing father. Terrence Howard and Thandie Newton play an affluent black couple who are humiliated by Sgt. Ryan.

There is also a story arc involving an Iranian family’s troubles running a business and a Mexican laborer (played by Michael Pena) trying to do right. The Mexican laborer is arguably the most morally pure character in the film.

Some of the stories reaffirm liberal views on race. Sandra Bullock’s Karen character realizes all of her abuse against racial minorities comes from her own unhappiness. The Iranian family is discriminated against by ignorant Americans who don’t realize they’re not Arabs. Terence Howard’s Hollywood director character suffers from unrealistic racism on his production sets.

It all builds up to a message of: “can’t we all just put our differences aside and get along?”

The Left has moved on from this message to a more strident anti-white theme on racism. Only whites can be racist, there is no excuse for racism, racism is the worst evil, and whites must pay a severe price for it.

Three of the storylines are fairly politically incorrect on the subject of race, and explain why the cheesy film is so hated.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s In Defense of Prejudice here [3]

The black carjackers uphold racial stereotypes. Ludacris’s character, Anthony, is a black nationalist who sees all white behavior as racist. He is also disgusted by black degeneracy and hates rap (clearly a joke, as the audience knows Ludacris is a famous rapper). Even though he bemoans whites for seeing blacks as criminals, he is a criminal himself. His partner in crime, Peter (Larenz Tate), doesn’t see whites as inherently racist and likes contemporary black culture.

We’re first introduced to the carjackers as they argue in an upper-crust area of LA. Anthony says the servers at the restaurant they dined at were racist; Peter defends them. Anthony decries the suspicious glances and actions of the white people around them, especially Bullock’s character grabbing onto her husband as she notices the black strangers. He complains about how whites feel unsafe in non-white areas, but tells Peter that they should feel unsafe surrounded by white people. They joke that they don’t feel unsafe because they have guns on them. The two carjackers then uphold white suspicions by holding up Cabot and his wife at gunpoint and stealing their car.

The Cabots go back home and try to cope with the aftermath. Mrs. Cabot shrieks about the Mexican locksmith and worries he’s a gangbanger. Mr. Cabot tries to find the best political reaction to the carjacking. “Why did they have to be black?” he cries to his befuddled aides. The district attorney feels caught in a quagmire. Getting carjacked makes it appear that he has let crime get out of hand. He also can’t draw attention to the suspects’ race for fear of alienating the black community. Rick suggests giving a black public servant a medal to appease blacks. He suggests a heroic black fireman as a possible awardee. One of his aides informs that the fireman is, in fact, an Iraqi named Saddam. Rick quickly realizes he needs another plan.

He finds it in the officer shootout being investigated by Cheadle’s character, Graham Waters. The shootout took place between a white undercover cop and an off-duty black cop in the heat of road rage. The black cop drew his gun on the white cop first. The white cop fatally shot his assailant. Initially, Detective Waters believes the white cop is the guilty party because he has previously shot two blacks and doubts his version of events. He comes to realize there is something fishy about the dead black officer. The car wasn’t registered to his name and he discovers $300,000 in cash stuffed into the spare tire. He also believes the victim was high on cocaine.

This story is based on a real-life LA police scandal that has inspired several movies and TV shows. In 1997, white undercover officer Kevin Lyga killed a black man who threatened him with a gun during a road rage incident. That black man, Kevin Gaines, turned out to be an officer in the RAMPART division [4], an elite anti-gang squad. The RAMPART squad was primarily composed of non-white cops. Lyga had no idea his victim was a cop because the assailant threw up gang signs and was dressed like a gangbanger. Lyga was later cleared of wrongdoing when it was discovered that Gaines worked security for the Bloods-affiliated rap label Deathrow Records and had a history of road rage. The shooting later led to the exposure of RAMPART as wildly corrupt and unethical.

The squad is the basis for the movie Training Day and the TV series The Shield.

In Crash, the white cop isn’t as lucky as his real-life counterpart. DA Cabot decides he needs to make an example out of the innocent officer to please the black community. The DA sends an Irish fixer named Flanagan to pressure Det. Waters into playing ball. Flanagan says that if Waters tells the truth, the racism of white Angelenos will be confirmed. “Fucking blacks, huh?” He makes it clear to the detective that the black community is firmly behind the slain officer and they want “justice.” Flanagan persuades Det. Waters that black kids need a role model and he can’t turn the slain officer into another crooked cop. He needs to look like a hero, and he promises Waters it will be good for his career to hide the skeletons.

Waters, against his better judgment, agrees to play ball. Later, DA Cabot gives a speech to the public about the odious white cop and how the city will no longer tolerate racist police.

Both of these stories justify latent white assumptions about the new racial order. Whites are right to be wary around black men in ghetto attire and black complaints about white racism are ripe for mockery. Diversity encourages government officials to disregard the truth and punish the innocent to satisfy aggrieved minorities. Black racial solidarity favors their collective interests over the truth and good governance. Both storylines make liberals uneasy. It’s not proper to show blacks as criminals, as evidenced by television crime shows overwhelmingly depicting white rapists and murderers. You’re also not supposed to show the system to come down in favor of POC. It’s built on white supremacy and the system would always favor the white cop.

Those very real aspects of American life are not favored for the silver screen.

The film also shows an uglier side to immigration. The carjackers accidentally run over a Korean man who they mistake as a “Chinaman.” They hit him as he was about to get in his van. The Korean appears at first as an honest and hardworking immigrant. But it turns out the van he was driving contained Thai migrants ready to be sold into slavery. The upstanding immigrant is not so noble after all.

But the storyline that particularly angers critics is the John Ryan character. We are first introduced to Sgt. Ryan arguing with a black HMO representative over the phone. Ryan wants to get help for his ailing father. He ends his conversation by noting her name is Shaniqua, saying that’s all he needs to know about her competence. The audience is made very aware this man is a racist. Soon after the call, Ryan and his rookie partner Tom Hansen (Ryan Phillippe), pull over a wealthy black couple driving a nice SUV. Ryan brutalizes and humiliates the couple. He forces the husband (Terence Howard) to watch as he fondles his wife (Thandie Newton) and makes the black man apologize for causing a disturbance. Ryan lets them go, but Hansen is left troubled by the encounter.

Later that night, we see Ryan take care of his sick father who can’t even go to the bathroom without help. This is a very different image from the brutal officer we saw before.

Ryan visits the HMO office the next day to get his father better medical care. He comes face to face with Shaniqua and pleads his case. He bluntly says she just got hired because of affirmative action before launching into a rant about his dad. His father was a janitor who worked hard to start his own company. He primarily employed blacks and never showed any prejudice. But when the city began favoring minority-owned businesses, his business collapsed. Ryan pleads with Shaniqua to help out his father. Shaniqua ignores Ryan’s request and has him escorted out by security.

Arriving at the police station, Ryan learns his partner is getting reassigned. Ryan knows it’s due to Hansen’s perception he’s a racist. He tersely tells Hansen he will eventually learn to share his viewpoint.

Ryan and his new partner come upon a flipped-over car blocking traffic. Ryan rushes to the vehicle to rescue the trapped driver. Gas is leaking and a fire has started in another wrecked vehicle. Lo and behold, Ryan discovers the driver is the black woman he molested the night before. The woman screams and refuses Ryan’s help. Ryan consoles her and eventually gets her to calm down. He gently begins to cut off her seat belt when fire begins to reach the car. Ryan desperately tries to free the woman but is pulled out by his partner. The woman pleads for him to come back as she braces for a fiery death. Ryan dashes back into the vehicle to save the woman he previously violated and pulls her out of the car unharmed. He wraps her in his arms and consoles her as they watch the car burn.

Sgt. Ryan angers critics because it shows a racist as a heroic, upstanding man. He may hate blacks, but that won’t stop him from saving blacks from burning cars. He’s also a good son who came to hate blacks due to the wrong done to his father. Ryan is far from a villain, despite his brutal treatment of the black couple.

Racists are supposed to only be villains. This dogma was reinforced in 2018 [5] when Three Billboards Outside of Ebbing, Missouri was in Oscar contention. That film also had a racist police officer character who turns out to be a good guy. Critics railed against such a depiction and said it reminded them of glowing alt-right profiles. There is no redemption available for racists.

These are just some of the stories in the movie. A major downside to the film is the presence of too many plotlines and characters. Sandra Bullock’s role was totally superfluous, yet she gets top billing. The film’s premise of making all these characters crash into each other is incredibly hackneyed.

Crash is not a great film. It is cheesy and it leaves no room for subtlety or nuance. But it’s not a bad movie. The acting is top-notch and there is a good taste for aesthetics. The film is also unintentionally based. The film does more to validate common-sense views of race than it does to undermine them. There is no racial reconciliation outside of the racist police officer heroically saving a black woman. In an industry where the racist usually gets saved by a POC, it’s refreshing to see the reverse occur.

Crash is very much a product of its time. Something like it could not be made in our age of caustic anti-white racism. Failure to get along isn’t the problem — whites are the problem. Crash is ultimately hated for failing to uphold that dictate.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [6] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.