Remembering Florian Schneider (April 7, 1947 — April 21, 2020)

Posted By Scott Weisswald On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled885 words

Florian Schneider, one of two founding members of Kraftwerk and its primary creative director for most of the band’s existence, passed away on April 21, 2020. Schneider was responsible for some of music’s most fascinating, technically impressive, and culturally significant developments being brought to broader audiences. Schneider was born on April 7, 1947, in the French-controlled sector of postwar Germany. His father, Paul Schneider-Elseben, was an architect. He formed Kraftwerk with his Remscheid Academy of Arts classmate Ralf Hütter in 1970, initially playing music that could be broadly classified as “krautrock”; members of Kraftwerk during this period would go on to great fame playing this style, such as Klaus Dinger, who left the group and went on to form Neu! in 1971.

Schneider’s instrument of choice in his art school was primarily flute. He was quite skilled as a flautist in general, and proved to be adept at both composition and improvisation during his time playing in Organisation, an avant-garde-influenced group at his school. Schneider’s greatest contributions to music, however, were in his radical attitudes towards the use of processing effects on real instruments; electronic music in mid-century Europe was often focused on exclusive use of the synthesizer to compose in styles more reminiscent of classical music than what modern audiences know as “electronica” today. Kraftwerk’s breakout album, Autobahn, features heavily edited sections of Schneider’s flute-playing, including pitch-shift effects, vocoding, and electronic flourishes to imitate the call of birds. Schneider did not limit himself to the instrument of his youth, however; he began to experiment with sequencing, using a keyboard to trigger sounds during studio sessions and live recordings. (Schneider’s use of the “sampler” closely followed Throbbing Gristle’s Chris Carter developing a similar instrument.) Schneider’s fascination with the frontier of sound motivated him to pursue increasingly novel means of both production and processing, leading us to now-iconic soundscapes such as the use of Texas Instruments beeps and boops on various Computer World tracks and the use of bicycle chains, labored breathing, and gear clicking on Tour de France.

Schneider had a distinct advantage over those approaching sound with a similar DIY, post-punk ethos: he could actually play his instruments. There is an immediately discernible — and admirable — quality of cleanliness, precision, and focus on Kraftwerk’s recordings that can be attributed to Schneider’s obsessive perfectionism and ear for tone. His contemporaries in the broader “electronic” movement, such as the aforementioned Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret Voltaire, or their compatriots Faust, approached sound composition from a conceptual background as opposed to a musical one. The often-lackluster production and piercing sounds of these groups have their specific appeal, but Schneider lent Kraftwerk’s sound a near-robotic degree of competence and accessibility that would propel them to far greater heights than any of the aforementioned. This clean sound would inspire the development of techno music in Detroit in the 80s.

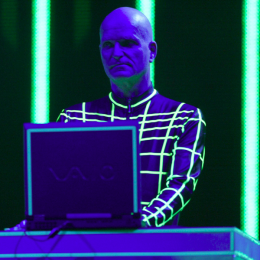

The “robotic” sound inevitably lent itself to robotic aesthetics, as well. Kraftwerk’s live performances mirrored the band’s music, being focused on precision, symmetry, and clarity of concept. The group would often perform without moving about the stage at all, instead manning their own station of synthesizers and audio processors. Beyond Kraftwerk’s simple musical appeal, the group was also intensely futurist, and their music maintains this quality even to the present day. This is likely because the Kraftwerk sound is largely inimitable; while it is easy enough to copy Kraftwerk’s methods (and many do), Schneider spent a large portion of his time in the band developing proprietary methods of sound generation that remained the band’s own. Schneider constructed the band’s own vocoders, his own flute-like electronic instruments, and the band’s primary recording studio — or “sound laboratory” — Kling-Klang. The group’s recording history could be considered an anthology of the band’s experiments with Schneider’s equipment; a series of journal articles documenting what they tested out over the years. Because of this, it would be exceedingly difficult to capture the band’s distinct ethos, one of near-constant invention, exploration, and instructive documentation.

Schneider, therefore, is an iconoclast in more ways than one. He was a musical and aesthetic innovator, developing artistic styles that would influence popular media for decades (and counting). But Schneider was also an example of the restless man; the European man who is motivated, or perhaps compelled, to make of his life and talents the best that he can. He was moved not by the idea of fame nor fortune to labor endlessly at his various inventions and compositions. He did so for their own sake, believing them to be whole works of art in and of themselves. In many ways, the wild success of Kraftwerk and the endless impact that the group had on the arts and cultures of the entire world affirms the inspiring notion that the work done by man’s own hand is never for naught. With focus, competence, and creativity, great things are bound to happen.

Schneider was an inventor, a maestro, and a role model. Let us never forget this operator with his pocket calculator.

You can find more on Kraftwerk from Counter-Currents here [1].

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [2] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.