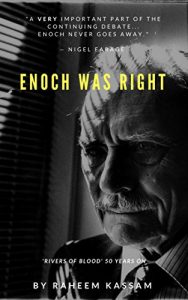

Raheem Kassam’s Enoch Was Right

Posted By Margot Metroland On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,473 words

Raheem Kassam

Enoch Was Right: ‘Rivers of Blood’ 50 Years On

Independently published, 2018

“Up like a rocket” is how Enoch Powell predicted his Birmingham speech would go on April 20th, 1968. And so it did. This, of course, was his “Rivers of Blood” speech, in which Powell warned of the catastrophic consequences of “new Commonwealth,” i.e., nonwhite, immigration to Britain, which had been going on for twenty years.

By comparison with the country today, the nonwhite faces were paltry, scarcely noticeable, but already their presence was disruptive. Famously, Caribbean blacks had rioted for several days in 1958 during the Notting Hill Carnival in London. Since that time, other disturbances and complaints of “colour prejudice” had led to a series of Race Relations Acts, designed to suppress racial conflict but actually inciting it. With the Birmingham speech, the public for the first time saw a prominent MP belling a cat that no other politician had dared to approach.

The Birmingham speech was not only front-page news (astutely, Powell had circulated copies of it beforehand), but was immediately, resoundingly, popular throughout the country. Powell was cheered everywhere he went — particularly in working-class districts and among trade unionists.

He was “tipped,” as the London papers say, to be the next Prime Minister. Alas, that did not quite happen.

In a fit of colossal idiocy, or pearl-clutching panic, Conservative Party leader Edward Heath decided to sack Powell from his shadow cabinet. Supposedly, Heath was trying to defuse controversy. But you have to suspect he was really protecting his own flank from possible rivals, as he looked forward to his own hoped-for premiership (in 1970).

Regardless, wiser heads advised against giving Powell the boot. Margaret Thatcher told Heath,

“Just read the whole speech and think about it for a few days.” Heath replied, “No,” and said Powell had to go immediately. He did. (p. 256)

Eleven years later (1979) Thatcher herself rode the immigration issue to electoral victory. Although, as Powell predicted at the time, she never followed through.

Powell had a long Parliamentary career after 1968, in both the Conservatives and the Ulster Unionist Party, and when he died thirty years later it was full of honors and gushing eulogies. “One of the great figures of twentieth-century British politics,” said Tony Blair. This is sort of surprising to read today. Poet-scholar-politician Powell was widely esteemed then. In the twenty-plus years since, his popular image has faded into something else:

As memories of the living, breathing Enoch faded, he ceased, for most people, to be a human being and became instead a symbol — a symbol of irrational hostility to immigrants. By 2007, a Conservative parliamentary candidate in the West Midlands was forced to stand down after asserting, in a newspaper, that Enoch “was right.” (p. 280)

This trim little book is a pleasure to read, because the author clearly loves his subject and seldom strays from his thesis. On every page, this way or that, Kassam hammers in that point again and again: Powell in 1968 was perfectly correct. About the doubling, tripling, quadrupling of nonwhites, both immigrants and native-born, in Britain in the near future. He was right about the pressure on public services that this would bring, and the discomfort and displacement of English people from neighborhoods and employment opportunity. Powell once quoted, approvingly, a constituent who said that the black man would eventually have the “whip hand” over the white. Recent events suggest that this goal has now been attained and surpassed.

As befits a professional journalist (formerly of Breitbart London and Human Events) Raheem Kassam writes succinctly, with a copyeditor’s eye. We get short paragraphs of easily digestible, butter-like prose. He gives us the whole “Rivers of Blood” speech at the front of the book (most people have read only snatches of it), and then readily requotes relevant passages where pertinent. No back-flipping or endnote referencing needed!

He also gives us a pop-historiographical profile of the post-1968 Powell. There is an extensive interview with Nigel Farage, who first met Enoch Powell during Farage’s schooldays at Dulwich College. This touches on Thatcher’s admiration for Powell, and how she drew support away from the National Front during her first election as Prime Minister in 1979. And of course, the idea of Enoch Powell as the godfather to UKIP, since Powell’s one undeniable and successful legacy is the belief that Britain must withdraw from the European Union.

Kassam excerpts some shrewd and revealing passages from TV interviews with David Frost and Michael Cockerell (whom he spells Cockerill, apparently confusing him with the Australian football writer). In both cases, the interviewers seek to corner Powell with “gotcha” questions about “Rivers of Blood.” Haughtily and sinuously, Powell tells them to go jump in a lake.

Cockerell’s questioning is part of a 1995 documentary called Odd Man Out: A Film Portrait of Enoch Powell. At one point he asks Powell to agree that the 1968 speech was “inflammatory and could be used by people who were racialists, against black people in this country.” And Powell replies, “What’s wrong with racism? Racism is the basis of nationality.” (p. 205)

Years earlier (1969) David Frost repeatedly pestered Powell about possible regrets the MP might have had:

FROST: . . .You’re almost saying you don’t really think you’ve made a real mistake, you’ve really done anything wrong.

POWELL: Ah, now you’ve pushed me in a corner. That sounds too self-satisfied, doesn’t it? All right, well, I’ll have to be self-satisfied.

That line drew the largest and longest applause of the entire grueling interview, as well as a chorus of laughter. (pp. 153-154)

One of Kassam’s more penetrating observations is that the original Race Relations Act (this was 1965) was self-defeating, as it increased instances of supposed discrimination. “Instead of creating a mechanism by which to deter discrimination . . . it created an industry.” (p. 213) He quotes from a book by Russell Lewis, Anti-Racism: A Mania Exposed, listing multiple instances of preposterous “discrimination” claims. For example, a doctor in the South of England advertising for “Scottish daily help” who could cook porridge for a Scottish family. And a Pakistani gentleman who specifically sought an “English lodger” because he wanted to teach his children English!

What is Kassam’s personal interest in the racial problem? He gives us an anecdote. When he was a boy of 15 (this would be about 20 years ago) he was going to play football with some friends, and had his mother drop him off at a bus stop in Hayes, west of London. His mother warned him to watch out for black people.

“Don’t be a racist,” I snapped back at my mother.

A few hours later I returned home, sweating and white as a sheet. On the top deck of the bus through Harrow, I had been mugged by three black men who took my CD player, my case of 50 CDs, my mobile phone, and all my money spare the two pounds I slipped into my left sock when they weren’t looking.

He could probably expand on this theme, but doesn’t, because the book is not about Raheem Kassam. He himself is of Indian background, though his parents were born in Tanzania. For many decades, Indians were a kind of “model minority” community in England: quiet, hard-working, self-contained, not the sort to mug you on omnibuses. But nowadays, in journalistic and political parlance, they’re grouped generically with other Subcontinentals as “Asians,” or worse.

It all reminds me of the time the writer Bill Hopkins took me out to dinner at an Indian restaurant in his North Kensington neighborhood (across the street, in fact, because Bill seldom strayed far from home). Somehow our conversation turned to the dissolution of the Empire. Bill’s eyes lit up, much as Enoch Powell’s are said to have done, when the topic was India. “You must understand, India was part of us!” And then went on about how losing India, losing the bond with the Indians, was the greatest tragedy of the whole mess.

This seems to have been a widespread sentiment among Englishmen of earlier generations, and one that Kassam has absorbed by osmosis. The Britain he loves and wants is the Hopkins version, where the Englishman and Indian eye each other with friendship and mutual respect, and do not regard Commonwealth immigrants as all of a piece.

Quite understandable, and one can easily sympathize. But I suspect this widespread respect for worthy, brown Orientals was really a “gateway drug” for British passivity, while the country was inundated by the less worthy ones — be they brown or black.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [1] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [2] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.