Remembering Charles Wing Krafft: September 19, 1947–June 12, 2020

Posted By Greg Johnson On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled 3,784 words

3,784 words

Charles Krafft is my name,

America is my nation,

Seattle is my dwelling place,

And art is my salvation.

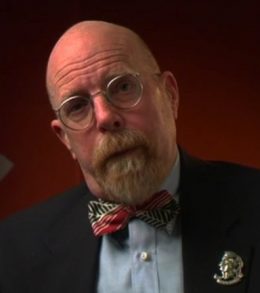

Charles Wing Krafft — painter, porcelain artist, and provocateur — died peacefully in the early morning hours of Friday, June 12 after a two-year battle with cancer. He was 72.

Krafft’s more than fifty-year career as an artist encompassed both fine art (he was a painter of the Northwest School) and so-called “lowbrow” pop art (his world-famous ceramics). He was also a poet and essayist. Although he traveled widely, he lived most of his life in and around Seattle.

Charlie Krafft was born in Seattle in 1947 to an upper-middle-class family. His father was a Boeing executive, his mother a housewife. He attended racially integrated public schools, which even then were rife with violence. To protect him from bullies, his parents placed him in the exclusive Lakeside School, but after three years, he flunked out and spent his last year at Roosevelt High School, from which he barely graduated in 1965. Immediately after graduating, he ran away from home, heading to the Bay Area where he stayed with his cousin Grace Slick and her husband. (Born Grace Wing, she is the daughter of Charles’ mother’s brother.)

At the time, Charlie wanted to be a Beatnik poet, but he realized that he could not live as a poet, so he tried his hand at painting and found he had a knack for it. Charlie also made money putting on psychedelic light shows at rock concerts. After he returned home to Seattle, his parents enrolled him in Skagit Valley Community College, which he attended while continuing to paint and do light shows. After one year of college, Charlie dropped out to devote himself to art full-time.

Charlie was mostly self-taught. “The only art credentials I have are the ‘astral apprenticeships’ I served under the reclusive painter of startled birds, Morris Graves (1910–2001) and the crackerjack Hollywood hot rod hero, Von Dutch (1926–1992)” (Juxtaposing [1]). Charlie also benefitted from the mentorship of Northwest painter Guy Anderson (1906–1998) and learned the art of painting on porcelain from an elderly Seattle Hobbyist named Barbara Henderson: My “career in clay began in a suburban breakfast nook . . . the cozy clubhouse of a gang of sable-brush-wielding grannies who call themselves the Northwest China Painters Guild” (Salon [2]).

In 1968, Charlie settled in Fishtown, a group of abandoned fisherman’s shacks along the Skagit River, which became an artist and hippie colony. Charlie was a central fixture of Fishtown, its unofficial mayor: “Fishtown was a prolonged experiment in the style of deliberate simplicity celebrated by Thoreau and inspired by the example of two legendary Northwest Zen Buddhists, Morris Graves and Gary Snyder. . . . Throughout the 1970s, Fishtown existed as a year-round community and a marshy Mecca for a constant stream of nomadic young visitors from Seattle, San Francisco, and points beyond. It was one of the region’s most visible symbols of the youth quake that swept the country in the ’60s” (Charles Krafft, “A State of Mind, Not a Place,” December 2001, unpublished).

Early in his career, Charlie was drawn to the so-called Northwest School of painters, the principal figures of which were Kenneth Callahan (1905–1986) and Mark Tobey (1890–1976) as well as Guy Anderson and Morris Graves. Guy Anderson helped Charlie grow as an artist, but Graves was the greatest inspiration. The two became friends, and in 1991 Charlie created a mock-Masonic order called the Mystic Sons of Morris Graves, of which Charlie served as Grand Polmarch.

The Northwest School drew inspiration from the natural beauty and distinctive quality of light of the Puget Sound area, as well as Asian aesthetics. They were often called “Northwest mystics,” because of the influence of Asian philosophy, particularly Zen Buddhism. Charlie embraced both the aesthetic and mystical aspects of the Northwest School with enthusiasm, although he was more aesthetically drawn to Tibetan Buddhism than to Zen. He also read widely in Hinduism, Alan Watts, and Aleister Crowley.

Charlie went to India in 1970 to study yoga, arriving just after the Beatles departed. He returned in 1972, meeting Ram Dass (Richard Alpert). In 2001, he attended the Maha kumbha mela. Later in the 2000s, he tried to meet Miriam Hirn, Savitri Devi’s friend and literary executor, in Tiruvannamalai. All told, he made five trips to the East.

During his time in Fishtown, Charlie built a reputation as a painter. His works were featured in many group and solo gallery shows. In 1980, he moved back to Seattle, where he became a fixture in the local art scene, including a board member of COCA, the Center on Contemporary Art.

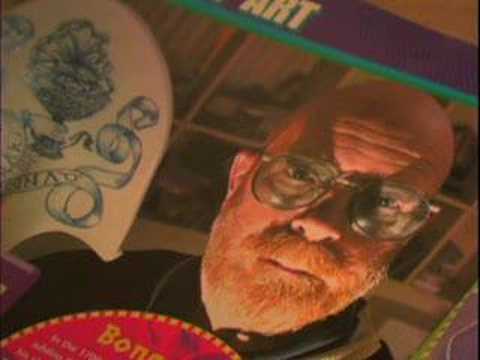

The second phase of Charlie’s career began in 1990, when he started corresponding with custom motorcycle and hotrod pinstriper Von Dutch (Kenneth Howard). Charlie’s friendship with Dutch was his introduction to the world of “lowbrow” art or Pop Surrealism. In Charlie’s words:

This is an alternative visual arts scene that has its roots in California custom car culture, surfing culture, and in ‘60s era underground comix. It’s a streetwise aesthetic that has been evolving and spreading out across the globe while remaining almost entirely unnoticed by most mainstream critics, museum curators, and art historians. It exists on the Internet and by word of mouth in its own parallel universe of events, magazines, galleries, shops, and studios in America, Europe, Australia, and Japan. (Juxtaposing [1])

Charlie’s friendship with Dutch also launched his career as a ceramicist. Charlie wanted to paint a portrait of Dutch in a distinctly Dutch medium: Delft-style, blue-on-white ceramic. So in early 1991, he began attending Barbara Henderson’s classes at the Northwest China Painters’ Guild.

The Von Dutch portrait was completed and shipped, but it was not well-packaged and arrived broken. This inspired Charlie to create Disasterware, a series of Delft-style plates commemorating disasters like the sinking of the Andrea Doria, the explosion of the Hindenburg, and the bombing of Dresden. As he told Salon [2] in 2002, “‘My idea was to drag plate painting kicking and screaming into the 21st century with these images of things you don’t usually find on tableware. It began as natural disasters — like floods — then it went into sociopolitical disasters where,’ he says, lowering his voice with mock gravity, ‘I’ve found the most comfort.’”

Until this point, Charlie had been a fixture in the local Skagit Valley and Seattle art scenes, but very much a local fixture. Disasterware garnered national and then international attention. “The moment I went from easel painting to ceramic painting, was the moment that the world started to take notice of me” (Salon [2]).

In the late-1980s, Charlie discovered Laibach, the Slovenian industrial music band which makes provocative use of nationalist themes and totalitarian (fascist and communist) aesthetics. In 1994, Charlie helped bring Laibach and other members of its Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK) collective to Seattle. In late 1995, Charlie went to Slovenia on a grant to make state dinnerware for NSK, which had declared itself an independent state, complete with its own passports. When Charlie arrived, the band declared him the official photographer for their Occupied Europe: NATO Tour. Next stop: Sarajevo, where they arrived in the burned-out city on the day the Dayton Accords went into effect to play a concert (bankrolled by George Soros’ Open Society Foundation).

The state dinnerware became a pair of commemorative tour plates, because Charlie’s time in Sarajevo inspired his next major project: his famous porcelain guns and other weapons, such as knives, brass knuckles, and hand grenades: “My aim is to produce a delicate arsenal of life-sized ceramic weaponry so gorgeous and patently functionless that they will bedazzle and confound everyone who sees them.” He returned to Slovenia in 1997 to make molds of various weapons and again in 1999 to display his work in the Porcelain War Museum exhibition. Originally, it was to be held in a gallery, but when the Slovenian military caught wind of it, they offered to host it at their headquarters in Ljubljana.

Charlie continued to come up with bizarre and macabre porcelain projects for the rest of his career. Two of my favorites are “Spone” (human bone china incorporating cremation ash) and his portraits of controversial figures: Adolf Hitler, Charles Manson, Aleister Crowley, Nick Griffin, Kim Jong-Il, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Vladimir Putin, Ted Kaczynski, etc., which come in various formats: normal busts, teapots, mugs, and even hot water bottles. His Ayn Rand comes only in piggy-bank form. His Mishima bust portrays the artist’s severed head.

I first learned about Charlie in connection with Laibach when I was living in Berkeley between 2002 and 2005. We first corresponded in 2004 or 2006 (I don’t have my old emails handy). We first met in 2009. He rapidly became one of my favorite people. He was one of the most imaginative, creative, and funny individuals I have ever known. He was utterly unique and irreplaceable.

Charlie was remarkably open to new experiences, people, and ideas. He was willing to listen charitably to any idea from any person. He had a disarming, childlike candor, as well as a Devil-may-care spontaneity, which I think were built on enormous underlying resources of courage and self-confidence, as well as a kind of mystical affirmation of the world, not necessarily as good, but as good enough for Charlie. I also admired how disciplined and hard-working he was when it came to art.

Sometimes, though, Charlie’s frankness verged on brutality. His openness usually served him well, but he often did not seem to understand that other people operate quite differently. His willingness to extend everyone the benefit of the doubt made him an easy mark for cranks, conmen, journalists, and other scum.

Charlie was a voracious and heterodox reader on art, religion, occultism, history, and radical politics. I always kept a notebook handy when I spoke to him, because he was a fount of fascinating recommendations.

Charlie had always been open to radical Right-wing ideas. One of his friends told me that sometime in the 2000s, when he and Charlie were waiting for a bus, Charlie recognized a man he had seen when George Lincoln Rockwell had spoken in Seattle in 1964, when Charlie was in high school. Charlie also had many friends on the Right. I won’t name any who are still living. But two notable ones are Von Dutch, who was a self-described Nazi, and Adam Parfrey, the half-Jewish founder of Feral House Publishing, who was the central figure of the West Coast Rightist counter-culture. The martial-industrial and neofolk music scenes were also filled with radical Rightists.

But most of these people thought that Charlie was merely a connoisseur of edgy opinions. Charlie was fascinated with intense religious and political commitments, but they were foreign to his personality. He was also quite candid about such heterodox interests. For instance, in 2002 he told Salon [2]:

Why was Ezra Pound a fascist? Here was one of the greatest poets of the 20th century. Why was he involved in this business? Here’s a very intelligent guy who knew everybody there was to know and he’s completely behind Mussolini. And when they release him from the asylum he’s unrepentant.

I’m deeply into exploring the other point of view in a certain time period, the ’30s and ’40s. I lose patience with the right-wing in America right now. I just think that they’re dunderheads. I’ve become a connoisseur of this kind of propaganda, but it has to be from a certain period — I can’t stomach Rush Limbaugh.

You see, I don’t have anything to believe in myself, really, and I’m wondering how another person comes into a belief system and becomes utterly convinced — it becomes theirs, it defines their personality, it defines their history as a human being. . . . Drifting into the realm of politics, how does somebody come to believe in a political system and embrace it and work for it and even sacrifice their lives for it, be committed to die for it?

I think Charlie found Rightist ideas attractive for the same reason he was fascinated with the occult and Eastern religions: they stimulated his imagination. But Charlie was not just interested in ideas; he was also interested in people, in believers, especially dissidents, i.e., believers who went against the current of the society around them. Charlie pursued these interests long enough and stubbornly enough — especially when the guardians of conventional wisdom started pushing back at him — that he actually became a dissident too.

During his travels in Eastern Europe in the 1990s, Charlie became interested in the Romanian Iron Guard. He actually interviewed a brother of Corneliu Codreanu. (This interview is historically significant and needs to be found and made available.) While in Romania, Charlie’s contacts mocked the widespread story that Legionaries hung Jews from meat hooks and tortured them during the Bucharest Pogrom of January, 1941.

Charles Krafft with Catilin Zelea Codreanu and his artist wife Rodica in Bucharest 2000.

Charlie’s initial reaction was, basically, “Why would people say it if it were not true?” But when faced with diametrically opposed, passionately held opinions, he decided he had to investigate. This led him down the rabbit hole into the world of World War II revisionism. Charlie spent years tracking down every source on the abattoir story. He would read an account, look at the sources, then track them down as well. In the end, he concluded that the Bucharest abattoir was just anti-Iron Guard, anti-Romanian, and ultimately anti-white propaganda. He wrote up his findings and sent them to the Holocaust Historiography Project’s Annual David McCalden Most Macabre Halloween Holocaust Tale Challenge competition, which awarded him first prize in 2005 [3].

Charlie also became interested in the related case of Romanian Orthodox Archbishop Valerian Trifa. He was convinced that the case for him being a war criminal was trumped up. In a 2012 interview, he stated, “I’m still interested in trying to help clear his name, and I’m one document away from proving that everything they said about this man was a load of horse puckey.”

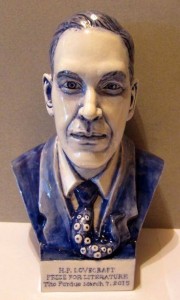

When I started Counter-Currents in 2010, Charlie was an early enthusiast. He did three interviews with Counter-Currents Radio. He attended and spoke at Counter-Currents Retreats (I will try to locate the audio). Charlie also spoke at the first Northwest Forum in 2016 and attended most of the others. His art adorns the cover of two of our books. He also wrote blurbs for three of them. When Counter-Currents launched the H. P. Lovecraft Prize for Literature, Charlie created the prize bust. When Counter-Currents launched its Centennial Edition of Francis Parker Yockey’s Works, Charlie created two plates commemorating Yockey’s 100th birthday.

When I started Counter-Currents in 2010, Charlie was an early enthusiast. He did three interviews with Counter-Currents Radio. He attended and spoke at Counter-Currents Retreats (I will try to locate the audio). Charlie also spoke at the first Northwest Forum in 2016 and attended most of the others. His art adorns the cover of two of our books. He also wrote blurbs for three of them. When Counter-Currents launched the H. P. Lovecraft Prize for Literature, Charlie created the prize bust. When Counter-Currents launched its Centennial Edition of Francis Parker Yockey’s Works, Charlie created two plates commemorating Yockey’s 100th birthday.

It was at a 2012 Counter-Currents Retreat that we noticed a change in Charlie. He started speaking as a white advocate, not just someone who was along for the ride.

Charlie’s heterodox interests and political journey were always public knowledge, but it took years for the forces of political correctness to catch on. Finally, on February 13, 2013, Jen Graves, an art journalist for the Seattle alternative paper The Stranger, published a hit piece called “Charles Krafft Is a White Nationalist Who Believes the Holocaust Is a Deliberately Exaggerated Myth [4],” which sent shudders of joy through the human centipede of the mainstream media, garnering coverage in The New Yorker, The Huffington Post, National Public Radio, and many lesser outlets. (You can read more about it in my essays “The Persecution of Charles Krafft [5]” and “Freude durch Krafft [6].”)

Tito Perdue with the first H. P. Lovecraft Prize for Literature

Charlie lost friends and galleries because of the controversy, but it seemed to me that he was most upset with people impugning his sincerity, since being open-minded and honest is what got him in trouble in the first place. He didn’t understand that Leftists are joyless cultists who live in constant fear of one another’s hysteria and intolerance, so why wouldn’t they impose the same conditions on their enemies? Making the entire world their madhouse is what they call “progress.” Still, Charlie never expressed any regrets about standing up for the truth as he saw it.

Charlie was famously cheap in his living, travel, and dining arrangements, and he had set aside money for his retirement (his father, Carl Krafft, lived to be 98). So he easily weathered the financial shocks of “cancellation” and found new outlets for his work. He traded fake friends for real ones. All told, he bounced back better than anyone I know who has been “outed” as a thought criminal.

Charles Krafft’s Yockey Commemorative Plates at the Francis Parker Yockey Memorial Dinner, September 18, 2017

In 2018, Charlie was supposed to take part in a show in Switzerland on weapons in art. But agitation from the usual suspects caused the gallery to pull out. Charlie decided to use his ticket to Europe anyway. He was supposed to depart on Sunday, March 11th. A friend and I had dinner with Charlie to see him off, and he seemed strange. For one thing, he ordered a drink at dinner. Charlie had a drinking problem in his youth but quit. So this was his first alcohol in decades. We chalked it up to pre-flight nerves.

When Charlie got to Europe, however, I began receiving messages from him that could only be deemed “confused.” He went to Budapest on March 15. John Morgan and Mike Polignano thought something was off as well. When Charlie got back to the states, one of his friends thought he was having a stroke and rushed him to the hospital on March 23. It turned out he had a brain tumor. He went under the knife that day.

As soon as the tumor came out, Charlie was his old self. I joked that he should tell Jen Graves that he had been cured of “hate.” Charlie was fine for about a year, then the tumor came back, and he had another operation. After that, he had difficulty walking, but he retained his creativity and sense of humor. A third recurrence of the tumor was inoperable. He died in a hospice setting, cut off from friends and family to almost the end because of COVID-19 restrictions which were, of course, ignored so that privileged people could protest, riot, loot, and murder across the country.

The cover of Christopher Pankhurst’s Numinous Machines is a mashup of Charlie’s Aleister Crowley Hot Water Bottle and Francisco de Zurbarán’s The Veil of St. Veronica, circa. 1635

After his first surgery, I dedicated my book Toward a New Nationalism “To Charles Wing Krafft, in friendship, respect, and gratitude. You really had us scared there for a while, Charlie.” By the time the book was in print, though, the cancer had already recurred.

Charlie should have had many more happy and creative years ahead of him, but with his body collapsing under him and his nation collapsing around him, I think he was increasingly ready to face the great mystery, always open to the end. He told a friend a few months before his death, “The seer I want to be shudders agasp, as he stares into a space more vast than death.”

Goodbye, Charlie. Wherever you are, I know you’re smiling.

***

Charles Krafft belongs to history now. In the future, dissertations and books will be written about his life and work. Thus it is important to preserve as much information as possible, especially given the ephemeral nature of online publication. If you have reminiscences of Charlie, audio versions of interviews Charlie gave to various podcasters, and electronic or print copies of his writings and correspondence that you would like to share, please contact me at [email protected] [7]. I will make sure that all such material is archived and made available to scholars.

Charles Krafft at Counter-Currents:

- Interview with Charles Krafft, Part 1 [8] (with transcript), April 29, 2012

- Interview with Charles Krafft, Part 2 [9] (with transcript), May 6, 2012

- Interview with Charles Krafft [10], March 12, 2013

- Greg Johnson Interviews Charles Krafft [11], January 17, 2014

- Charles Krafft, “What’s Wrong with the Arts? [12],” November 24, 2016

Note: We are looking for volunteer transcribers for the last three audios.

Matthew Drake’s video for an excerpt from Charles Krafft’s speech from the first Northwest Forum. Please share and like.

Source: https://youtu.be/qo7I6qikGko [13]

About Charles Krafft:

- Greg Johnson, “The Persecution of Charles Krafft [5],” February 14, 2013

- Greg Johnson, “Freude durch Krafft [6],” February 27, 2013

- Greg Johnson, “The Counter-Currents H. P. Lovecraft Prize for Literature [14],” November 12, 2015

- Greg Johnson, “Charles Krafft’s Francis Parker Yockey Commemorative Plates [15],” December 5, 2017

- Jef Costello, “Bi-Coastal Adventures in Modern Art [16],” October 18, 2013

- F. C. Stoughton, “An Open Letter to Kurt Anderson on Charles Krafft [17],” April 9, 2013

- F. C. Stoughton, “Home Remedies for Hitler Hysteria Prescribed by the New Right Avant-Garde [18],” February 28, 2014

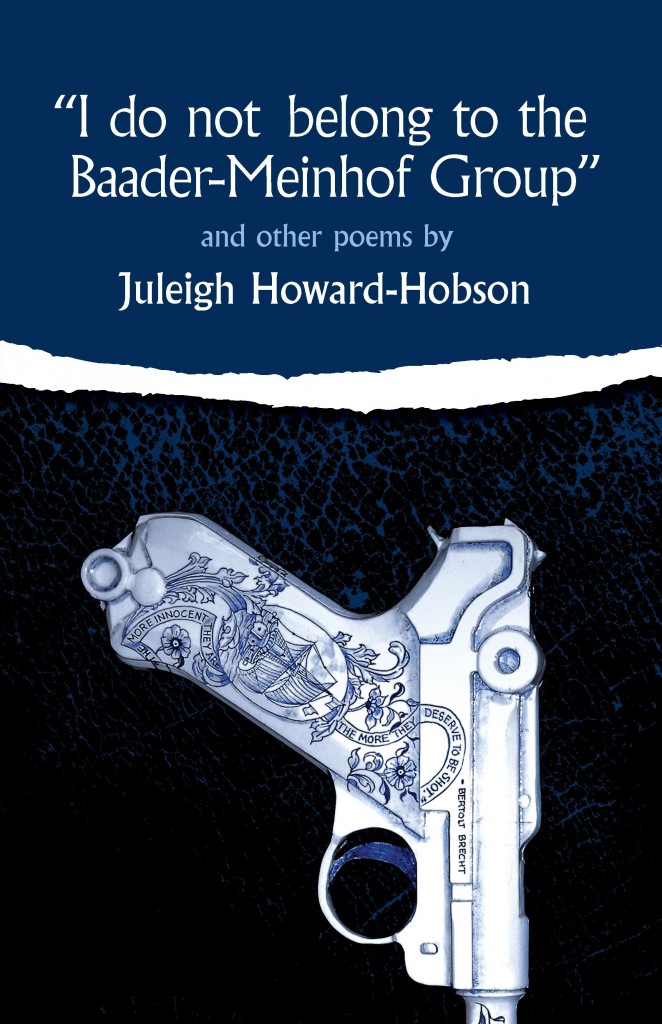

- Juleigh Howard-Hobson, “Turning Point: Mjolnir Magazine, Issue 2 [19],” July 6, 2015

- David Yorkshire, “The Alt Right and the Arts [20],” November 2, 2016

Charles Krafft’s Blurbs for Counter-Currents Books:

For Greg Johnson’s Truth, Justice, & a Nice White Country:

“Greg Johnson lifted me out of an intellectual gutter of losers and pastors I’d fallen in with after a Slam & The Ice Picks concert in Idaho back before the iPhone. He introduced to me to a loftier level of thinkers who speak and write in complete sentences and don’t sport Viking tattoos. Superb writers on the right side of the political spectrum who ended up on the wrong side of history like Ezra Pound, Martin Heidegger, and Savitri Devi. Greg’s mentoring moved me off the freeway to prison I was speeding along and put me on the path to full acceptance of my inner tweed and tortoiseshell white self. If he can work a miracle like that for me he can do the same for you.” — Charles Krafft, Villa Delirium Delft Works

For Greg Johnson’s In Defense of Prejudice:

“Imagine an angelic-looking guy in leather pants named Peter Probabilistic who is the lead singer in a supergroup called the Inductive Generalizations. Then imagine you’re one of thousands of excited fans who have filled a stadium to see them perform songs from their new chart topper In Defense of Prejudice. In what sort of world would a concert like this be happening? If your answer is Disney World® that’s wrong. Find out exactly how wrong in this new collection of essays by Greg Johnson.” — Charlie Krafft, Villa Delirium Delft Works

For Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right (and More Artists of the Right):

“Kerry Bolton is the Noam Chomsky of the New Right. His double doctorates in theology and encyclopedic knowledge of 20th-century history qualify him as a guru, and as such I recommend his writings on geopolitics, culture, and spirituality to anyone with more than a passing interest in these subjects. Every day since VE Day has been a Marxist holiday for the culture makers of the West. Artists of the Right is a declaration of the manifest bankruptcy of this legacy.” — Charles Krafft

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [21] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [22] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.