The End of the Frontier

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,963 words

Greg Grandin

The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America

New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2019

In this excellent and quick-to-read book about the border wall and its place in history, Greg Grandin builds upon the work of historian Frederic Jackson Turner (1861–1932). At the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, Turner gave a speech that has come to be called the “Frontier Thesis [1].” He’d been prompted to give the speech because the US Census Bureau had determined after the 1890 census that “The Frontier” had closed. The Frontier, by definition, was the part of North America that was not settled by whites and where land was essentially free or cheap.

Frederick Jackson Turner argued in 1893 that the existence of The Frontier helped create American liberty. His ideas inspired politically powerful and ambitious men in the McKinley administration to wage an imperialist war against Spain in 1898.

Turner rejected the idea that American cultural forms originated in the forests of Denmark and Northern Germany that was hitherto dominant in most American university history departments of the time. Instead, he argued that the existence of the frontier created the American forms of liberty, such as a large middle class, no aristocracy, etc. Turner’s speech was not enthusiastically received in Chicago. The audience politely listened and there were no questions at the end of the talk. But when word of the contents of the speech got out more broadly, people took notice.

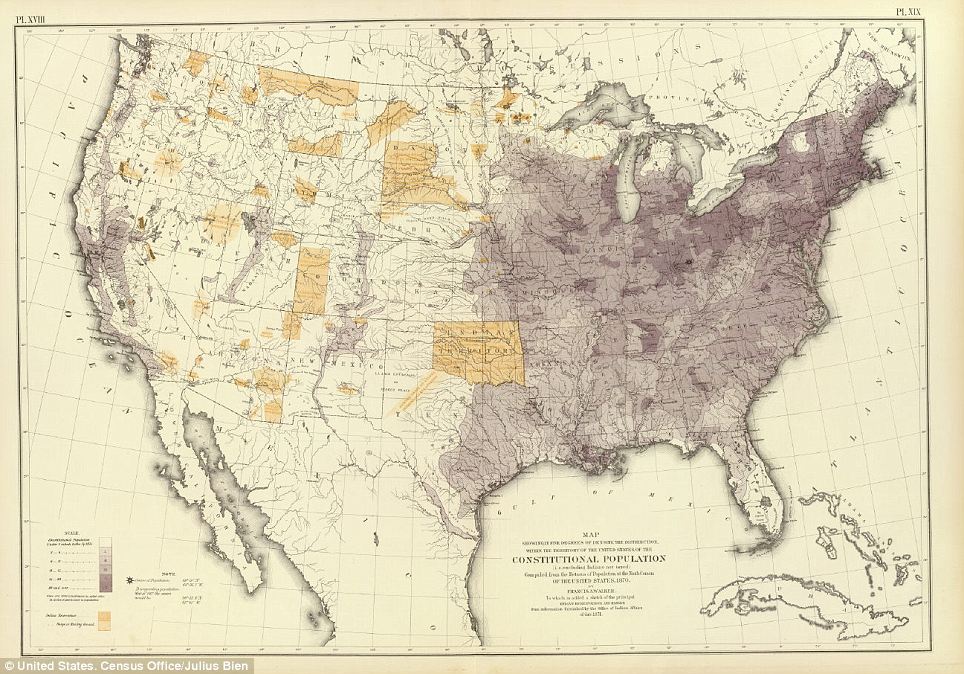

The frontier in 1870. Within two decades all of North America would be settled by whites.

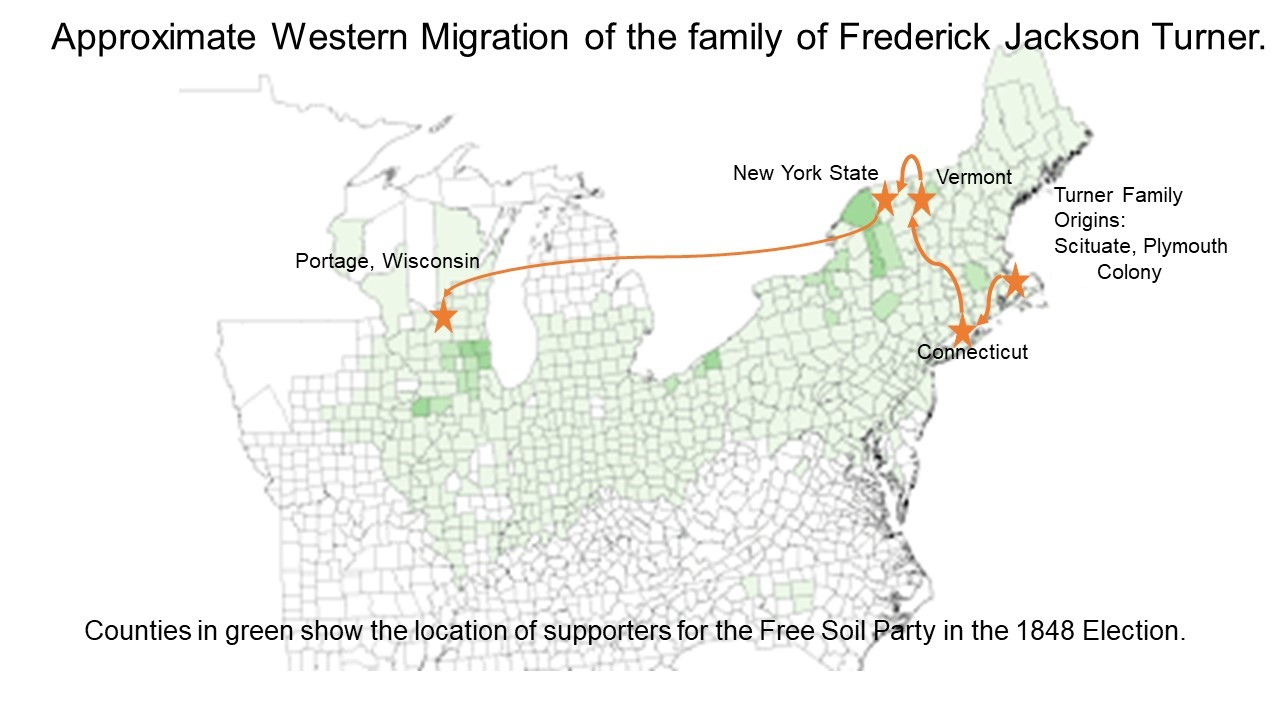

Turner himself was a product of America’s western expansion. He was of New England Yankee stock whose ancestors originated in Plymouth Colony. The Turners then went on to the frontier of Connecticut, thence to Vermont, then to Upstate New York, and then to Wisconsin. Turner’s father, Andrew Jackson Turner (1832–1905) was a prominent Wisconsin politician who removed Indians from Wisconsin to reservations in Nebraska.

Grandin shows that Turner was building on the ideas of Western Expansion that were encouraged by President Andrew Jackson and his supporters, but with the racial angle played down. This was a break from the past, more suited to a multi-racial Empire than a self-governing ethnostate.

Earlier, President Jackson wished to make the whole of the United States a Saxon ethnostate where ordinary white families could do well and get ahead. Jackson looked at the situation and concluded the Texas Republic should be annexed to these ends, war with Mexico should go forward, and the Indians removed. Jackson made no apologies and didn’t mince words. He took it easy on the Slavery Question. He allowed slavery to expand in the South, and Free Soil men to expand in the North equally.

President Jackson, and his allies like Thomas H. Benton (1782–1858), saw the frontier as a “safety valve” for America’s social problems. Should a factory worker lose his job at a Rhode Island mill, he could take his family and start over on the frontier. Once the frontier closed, however, unemployed Rhode Island mill workers needed to be accommodated in some other way.

That is what made Turner’s Chicago speech so powerful in the 1890s. People like Theodore Roosevelt were certain that the United States needed a new frontier to continue the “safety valve” process. They accomplished this through a second version of the Mexican War, only this time with Spain.

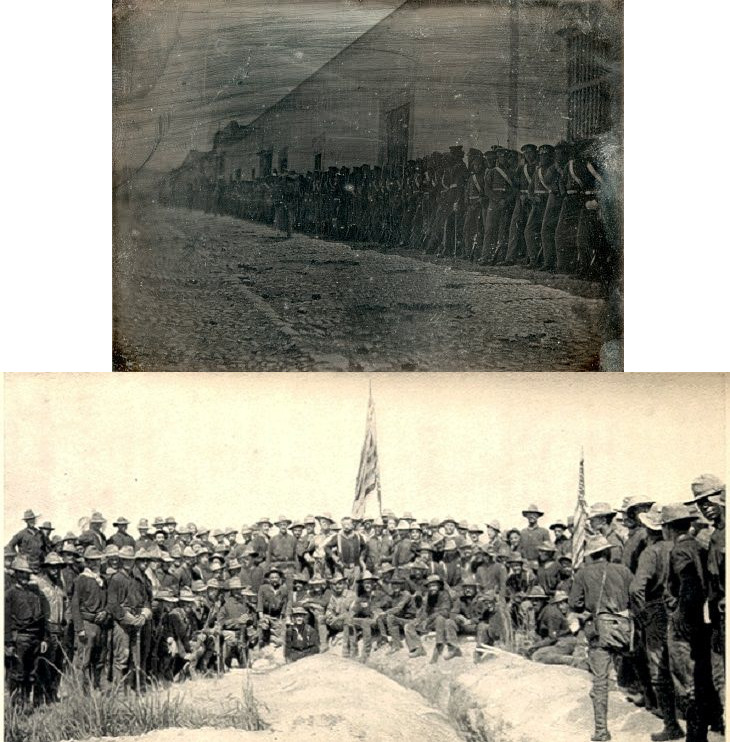

Top: US Soldiers during the Mexican War. Bottom: Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders during the Spanish American War.

The Spanish-American War was something of a funhouse-mirror image of the earlier Mexican War. Unlike northern Mexico in 1846, the conquered territories already had large populations, so American’s couldn’t settle there in large numbers. America didn’t get farmland as much as charity cases from the War with Spain. While the Mexican War made American domestic politics red hot and polarized between North and South, the Spanish-American War united the two halves of America like never before. Grandin argues that

. . . [T]he country’s many overseas wars, has played [a role] in keeping the symbols of the Confederacy alive. Starting around 1898, well before it became an icon of redneck reaction, the Confederate flag served for half a century as a symbol not of polarization but of national unification, a prideful pennant in an extending American empire. It was a reconciled army that moved out into the world after the Civil War, as new wars allowed those who fought for the Confederate Army, and the children of those who fought, to be readmitted into the nation. But reconciliation took place not just between soldiers who wore the blue and those who wore the gray. Also reunited was an unstoppable combination of northern law—bureaucratic codes, hierarchies of command and control, industrial might, and technology—and southern spirit, an “exaltation of military ideals and virtues,” including valor, duty, and honor. (p. 132)

Indeed, in 1898 “entire divisions” shipping out to fight the Spaniards sewed Confederate patches on their uniforms. The first flag flying over the captured Japanese headquarters on Okinawa was the Rebel Banner. During the Korean War, sales of Confederate flags went from “forty thousand in 1949 to sixteen million in 1950. Much of the demand was coming from soldiers overseas in Germany and Korea.” (p. 145)

American troops march with the Confederate Flag in Lebanon.

The Last Wars of the Frontier

Grandin goes on to describe how American political leadership continued to direct American social pressures, especially racial ones, outward through military expansion in detail. This includes considerable information on American economic policy in Mexico after the US Civil War but prior to the Mexican Revolution in the early twentieth century. Ronald Reagan, for example, channelized the white reaction to the “civil rights” disaster into an anti-Communist crusade in Central America.

Indeed, Bill Clinton channelized white anger at black crime into support for NAFTA, which Grandin argues was devised under the philosophy of expanding the frontier. In a speech given to Sub-Saharans at a black church in Memphis, Clinton invoked the Reverend Doctor Martin Luther King Jr., but with a more responsible twist than anything the saintly Reverend Doctor ever said:

“I did not fight for the right of black people to murder other black people with reckless abandonment,” Clinton imagined King as saying. Elsewhere on that trip, Clinton pitched NAFTA more directly. Economic expansion, not targeted federal intervention to destroy the structural foundation of racism, would provide the wealth needed to bind communities and families together and end “ghetto pathology”. . . But by making globalization part of the cultural critique of black men, Clinton was giving Republicans and conservative Democrats another reason to vote for the treaty. The official line was that global growth would help the country overcome poverty and racism. The unofficial line, though, the “subliminal” message, was clear: global competition would discipline the black underclass and help the Democratic Party break its dependence on groups like the Congressional Black Caucus. (p. 235)

Lyndon Baines Johnson, a Jacksonian president if there ever was one, presided over America’s first Frontier War that went badly. Grandin shows how the aftershocks of Vietnam aided in deindustrialization in the 1970s. The biggest irony of LBJ’s presidency was not Vietnam, but the fact that a genuine heir to Andrew Jackson’s legacy empowered the mortal enemies of Jackson’s fervent white supporters.

Johnson signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which is now an anti-white illicit second constitution as well as the 1965 Immigration Act that allows Third World People to come to America. He also empowered non-whites politically and economically. After 1964, American politics became polarized around non-whites represented by Obama, and Jacksonian whites, today represented (poorly) by Trump and the Republicans.

This increasing racial ugliness and polarization is the result of the “safety valve” of foreign conquest in the frontier failing to work. Grandin writes,

Had the occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq not gone so wrong, perhaps Bush might have been able to contain the growing racism within his party’s rank and file by channeling it into his Middle East crusade, the way Ronald Reagan broke up the most militant nativist vigilantes in the 1980s by focusing their attention on Central America. For over a century, from Andrew Jackson forward, the country’s political leaders enjoyed the benefit of being able to throw its restless and angry citizens — of the kind who had begun mustering on the border in the year before 9/11 — outward, into campaigns against Mexicans, Native Americans, Filipinos, and Nicaraguans, among other enemies.

But the occupations did go wrong. Bush and his neoconservative advisors had launched what has now become the most costly war in the nation’s history, on the heels of pushing through one of the largest tax cuts in the nation’s history. They were following the precedent set by Reagan, who in the 1980s had slashed taxes even as he increased the military budget until deficits went sky-high. Yet news coming in from Baghdad, Fallujah, Basra, Anbar Province, Bagram, and elsewhere began to suggest that Bush had created an epic disaster. (p. 254)

Did the American Frontier End in Iraq?

The question raised in this book, of course, is had the Bush administration won in Iraq, would American domestic politics have taken the racially polarized turn that it did? Possibly, but racial politics have always been simmering in America and it was only a matter of time before this issue came to the fore in a way that cannot be ignored. The problem comes down to “civil rights.”

9/11 and the following Iraq War debacle were a direct result of “civil rights.” Had the mechanisms remained in place that kept out Third World people, such as the hijackers, there wouldn’t have been a 9/11 in the first place.

The “civil rights” problems are also at the bottom of the Iraq War debacle. The US military has had problems with blacks since 1898, but those problems were contained as best they could be by senior leaders able to frankly discuss and manage African pathologies as well as segregation. When segregation ended and “civil rights” became the dominant narrative alongside veteran worship, blacks in the service could not be criticized or honestly managed.

In Iraq, blacks remained crime-prone, contributed little to no intellectual material to adjust policy or tactics, and generally gummed up the works. I know one Iraq War soldier who had to carry out a shell game of personal moves and phone calls while he was stationed in Tikrit for more than a week to get rid of a black supply sergeant who was using the supply room for trysts with an enlisted Shaniqua. The trysts wouldn’t have been a problem, but nobody could get toilet paper and the resentment was building. Meanwhile, of course, the insurgency grew.

The worst part, though, is the effect they have on senior officers. Those that make high rank end up being men who misread data and/or cover over black dysfunction. Hence, a certain General Casey responds to a highly-predictable mass shooting carried out by a Muslim in the ranks by praising “diversity.” It was only a matter of time before America’s Africanized Army would stumble.

“Civil rights” ended the frontier on Earth as much as it ended, or at least suppressed, the frontier in Space.

Of course, what comes next? I offer the following: We know what America’s borders are. It is time to seek the frontier of the white ethnostate.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [2] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [3] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.