The Last Battle Part I: Might Makes Right

Posted By Giles Corey On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled

Justice Robert H. Jackson at the Nuremberg Trials.

8,526 words

David Irving

Nuremberg: The Last Battle

London: Focal Point Publications, 2004

Author’s Note: Thanks are due to the great Mark Weber of the Institute for Historical Review [1] for his editorial advice. Mr. Weber’s own discussion of the tragedy that was the Nuremberg Trials is well worth your time, and can be accessed here [2] and here [3].

Teutonic sagas relate that after the great battle with the Mongols on the Lechfeld plain, where the armies of two different worlds had clashed in violent and bloody massacre, the spirits of the fallen warriors had continued the struggle for three more days above the clouds. So it had been in Nuremberg too: where the city’s face bore the terrible scars of the mortal struggle between Germany and her enemies which had ended in May 1945, the ghosts had continued the struggle for sixteen more months. But there the parallel ended: the armies were unequal now; one side was unarmed and had few friends.

The indispensable David Irving gives us the most comprehensive, truthful account of the Nuremberg trials, the last battle of the Second World War and the last stand of the Third Reich, that we will ever have. Though Irving needs no introduction, we must note that, as per usual, his ability to locate obscure diaries and official documents is nothing short of uncanny; his scholarship in this work is impeccable, and beyond reproach. The International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg was the first such kangaroo court of its kind, an attempt at creating of whole cloth an edifice of “international law” set against “war crimes” and “crimes against humanity.” Irving presents the definitive, kaleidoscopic account of how the events at Nuremberg came to transpire, and how they ultimately concluded. The Nuremberg trials are significant today for several reasons; perhaps of most relevance for us, the fact that not only was the defeat of Germany in war bizarrely enshrined in “law” through the trappings of an ostensibly objective trial proceeding carried out by her conquerors, but indeed that these show-trials were the first time that white identity, and racialist thought writ large, were quite literally criminalized for good measure. Nuremberg thus forms one of the pillars of the regnant Jewish supremacism masquerading as egalitarianism under which we have been brutalized and humiliated for almost the entirety of the last century.

The Second World War was retroactively fashioned into a crusade against “racism” and “anti-Semitism,” and the Cold War that was that war’s immediate consequence cast the United States as a “universal creed,” an ideology rather than a nation of blood and soil. The Nuremberg defendants might have been German leaders, but it is clear that at one level of abstraction, they were stand-ins, avatars of the entire white race; it was here that, by proxy, white ethnocentrism was declared morally evil and indefensible. It was here that the Allies and their masters solidified their moral righteousness in the history books, allowing the Euro-American public to believe that they had fought and died for something, that two generations of the best men of the West had been obliterated for a reason, for the achievement of unquestionable good. The Nuremberg trials allowed us to forget that, in Kevin Strom’s words [4], they fought and died for a race whose goal is their extinction, which has stolen nearly all the wealth that is rightfully theirs, which has erased the borders of their nation, which has twisted their spiritual life, which is replacing them with hate-filled aliens in the land their ancestors built, which has rendered them powerless in their own nation, and which has corrupted, captured, degraded, and made sexual slaves of their women. They shed the blood of their brothers on behalf of a race which wants us all erased, a race whose mission will not be complete until the very memory of our names evaporates as if we had never lived.

As the fighting in Europe drew to a close, Allied leaders began to debate what they should do with captured German leaders. By and large, the climate within the Roosevelt Administration was one of unmitigated hatred. At a stag dinner held at the White House, President Franklin Roosevelt regaled Polish Prime Minister Stanislas Mikolajczyk with stories of Stalin’s plans to “liquidate fifty thousand German officers,” and he had laughed out loud as he recalled how his Joint Chiefs had listened with round eyes to these words.” Henry Stimson, his Secretary of War, cautioned Roosevelt and suggested that the ethnic cleansing of Germany be committed after American forces turned over the northern German ports; he “felt that repercussions would be sure to arise which would mar the page of our history if we, whether rightly or wrongly, seemed to be responsible for it.” Stimson wrote that America should remain in the southern sector of occupied Germany, for it would “keep us away from Russia during occupation…Let her do the dirty work.” Secretary of State Cordell Hull proposed essentially to execute every German officer, from top to bottom. Lord Halifax, the British Ambassador to Washington, wrote that his barber continually exhorted him to “kill every one. Leave one — they will breed again and you have to do the job again. It is like leaving one rabbit in a young plantation.”

General Dwight Eisenhower told Halifax that the German prisoners should be “shot while trying to escape,” and Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff, Walter Smith, urged that, with respect to the nearly four thousand German officers designated as belonging to the (nonexistent) German “General Staff,” “extermination could be left to nature if the Russians had a free hand.” Eisenhower replied: “Why just the Russians? The victorious powers could temporarily assign zones in Germany to the smaller nations with scores to settle.” Eisenhower continued, “The whole German population is a synthetic paranoid, and there is no reason for treating a paranoid gently. . . The ringleaders and the SS troops should be given the death penalty without question, but punishment should not end there.” The infamous Jew Henry Morgenthau, Secretary of the Treasury, agreed with Eisenhower’s idea of perpetual punishment, declaring that “the German people must not be allowed to escape a personal sense of guilt. . . The German General Staff should be utterly eliminated.”

As alluded to above, Irving notes that in Hitler’s time, i.e., during the Third Reich, “there was no General Staff for all the armed forces as there had been in the Great War — it was a figment of the Allied propagandists’ imagination.” Though we need not dwell on Morgenthau’s Plan, it will suffice merely to restate the proposal as Morgenthau outlined it to the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, summarizing “the desirability and feasibility of reducing Germany to an agrarian economy wherein Germany would be a land of small farms, without large-scale industrial enterprises.” Churchill later noted that Morgenthau’s hatred for the German people was “indescribable.”

When Morgenthau told Roosevelt that some of the European nations were planning a “soft” future for the fallen Germany, the President replied, “Give me thirty minutes with Churchill and I can correct this. We have got to be tough with Germany, and I mean the German people. . . You either have to castrate the German people or you have got to treat them in such a manner so they can’t go on reproducing people who want to continue the way they have in the past.”

This latter statement emphasizes one of the important tactics deployed at Nuremberg — and then throughout the twentieth century — with National Socialism, and then Germany, and then white ethnocentrism altogether pathologized into some kind of psychiatric aberration from the purportedly egalitarian state of nature. Morgenthau further proposed that all able-bodied Germans be enslaved and transported to Central Africa to be used as labor for some unknown and unnamed Tennessee Valley Authority project. The American public did not receive news of these extremely vindictive proposals well, so Churchill, whose government had already endorsed summary execution of German prisoners-of-war, urged that the Allies “kill as many as possible in the field.” Churchill reveled in insensate carnage, celebrating that the war was the cruelest “since the Stone Age”; this, however, would appear to be quite an insult to our Stone Age ancestors, for their methods of warfare were most certainly far more honorable than those of “civilized” Europe in this most savage bloodbath in human history.

Wrecked American Sherman tank in Nuremberg.

Roosevelt was quite on board with ruthless barbarism, stating at Yalta that he “hoped Marshal Stalin would again propose a toast to the execution of fifty thousand officers of the German Army.” Indeed, the American President declared, “I do not want it too judicial. I want to keep the. . . newspaper photographers out until it is finished.” James Forrestal, Secretary of the Navy and future Secretary of Defense, who would later be assassinated for his opposition to Zionism, correctly recognized that “the American people would not support mass murder of the Germans, their enslavement, or the industrial devastation of their country.” The more cynical Stimson warned Roosevelt to play his cards closer to chest, arguing that “there ought to be a judicial proceeding before execution.”

Surprisingly enough, it was Soviet ruler Josef Stalin who stood alone among the Allied executives in desiring trials; as the Soviets were long inured to show-trials at which dissent was pathologized, though, perhaps this is not so strange after all. Stalin said that he wanted “legal” proceedings, for, he feared, “otherwise the world would say we were afraid to.” In all likelihood, the Nuremberg trials would not have happened had Roosevelt not died; his successor, Harry Truman, wanted the United States to take the “moral high ground,” or whatever moral ground that yet remained in the scorched earth of the ruined West. Lest we mistake Truman, the only man ever to order the use of nuclear weaponry, for an idealist, let us keep in mind that he merely agreed with Stimson that “the Nazis should be given a fair trial first — and then hanged.”

Cooler — though much more cynical — heads prevailed. President Truman appointed Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson to be the Chief American Prosecutor at Nuremberg; by all accounts, Jackson was an honorable man, though colored by biases (albeit to a lesser extent than his colleagues) against the Germans in the dock. He seems to have genuinely wanted to design a fair trial, but nevertheless had no doubt that the German defendants would be “convicted,” sentenced to death, and executed. Prior to his appointment, Jackson attacked the “cynics” who had expected war crimes tribunals to act merely as extended weapons of war. He had initially come out against any such trial. Indeed, as the war in Europe drew to a close, he had said that “if we want to shoot Germans as a matter of policy, let it be done as such, but don’t hide the deed behind a court. If you are determined to execute a man in any case, there is no occasion for a trial; the world yields no respect to courts that are merely organized to convict. It would bring the law into contempt if mock tribunals were held with the verdict already decided.”

He would later recall that he “expressed the opinion that if these persons were to be executed, it should be as the result of military or political decisions.” Upon his appointment, however, Jackson immediately encountered a labyrinthine web of intractable problems; aside from the terrible optics of the victors of a war attempting to color their martial victory under the flag of metaphysical “law,” his foremost issue was that there would be few crimes listed in the indictment of the German war criminals of which one or other of the four prosecuting powers was not itself guilty. In the cause of defeating Hitler, civilian populations had been — and were still being — burned and blasted, murdered, brutalized, intimidated, deported, and enslaved; aggressive wars had been launched, neutral countries had been occupied by pretext and deceit, and the unalterable paragraphs of the international conventions on the treatment of prisoners-of-war were still being flagrantly violated.

Jackson, along with the other Allied prosecutorial teams, was sensitive to the danger that the Nazi defendants might turn the tables on their victors during the coming trial, pointing the finger at their prosecutors and accusing the victorious powers of having committed crimes that were equal to, if not worse than, those of which they were accused. Jackson, possessing US Army leaflets which had been dropped over Japan depicting Japanese families consumed in flames along with threats of further American terror-bombing, admitted as much to Truman, writing that the Allies “have done or are doing some of the very things we are prosecuting the Germans for. The French are so violating the Geneva Convention in the treatment of prisoners of war that our command is taking back prisoners sent to them. We are prosecuting plunder and our Allies are practicing it. We say aggressive war is a crime and one of our allies asserts sovereignty over the Baltic States based on no title except conquest.” For just one example in a roiling sea of hypocrisy, America and Britain assented to the Soviet deportation of German soldiers and civilians for slave labor, and had plans of their own to do the same. Furthermore, the Soviets wanted all German men to be sterilized, and their women to be forcibly bred with Russians and “American” Blacks.

As we now know, and as Allied governments knew then, the American, British, and Soviet governments committed horrific war crimes on a vast, unprecedented scale, crimes which did not stop even after the German surrender. For example, in Soviet-occupied eastern Germany, the Russians massacred any and all prominent and respectable ethnic Germans, “all leaders, intellectuals, lawyers, civil officials, scholars — any who might be a rallying point for opposition.” In other words, what few good German men who survived the real holocaust were liquidated so that the new generation was comprised of cowards and criminals, a dysgenic Adam and Eve for a new, emasculated, Jewish Europe.

Irving incisively asks, “Would it be ungenerous to suspect that this was perhaps one reason why some of the Allied leaders consulted had hoped to silence the enemy ‘war criminals’ by declaring them to be outlaws and killing them off quickly, without first giving their day, or even their hour, in court?” In one conversation with Jackson, Senator J. William Fulbright suggested that there simply was no extant law under which the Germans could be tried, for the waging of war cannot be retroactively declared a “crime” out of petty hatred by those who won; therefore, Fulbright said, “they must be executed forthwith as a political decision. A trial means. . . giving the defendants a chance to tell their stories to the world.” Jackson replied with a remarkable query: “What are we afraid to hear them tell?” Fulbright declined to answer.

A further knot in what Jackson would come to see as a tightening noose was the issue of evidence — more specifically, the strange paucity thereof. Washington was full of people who assured Jackson that there was no doubt about German war crimes, particularly the events that would in the 1970s come to be known as “the Holocaust,” and general war guilt, which had also been ascribed to Germany at Versailles after the First World War. But when Jackson asked for specific evidence, he wrote, “I can’t get a single item.”

For his daring even to try to obtain provable evidence and run an even nominally objective trail, the philo-Semitic propagandist Drew Pearson attacked Jackson as “soft” in his Washington Post column, to which the Justice provided the excellent rejoinder, “Washington is full of cowards. Gallup-Poll patriots.” In the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Third Reich, what was known of the supposed Nazi “extermination camps”? Irving explains that “the most horrific camps were in the zones occupied by the Soviet army and thus not immediately accessible to the Allies. At many camps liberated by the British or Americans. . . they found and photographed for posterity disturbing scenes of death from starvation and pestilence — scenes which should not, in retrospect, have surprised the Allied commanders who had spent the last months bombing Germany’s rail distribution networks and blasting the pharmaceutical factories in order to conjure up precisely these horsemen of the Apocalypse.”

A perfect encapsulation of the evidentiary voodoo that went on during the Nuremberg trial preparations and proceedings is presented by the mythical figure of the “six million” dead Jews. In June 1945, visiting Federal Bureau of Investigation officials in New York, Jackson had his first meeting with several powerful Jewish organizations, represented by Judge Nathan Perlman, Dr. Jacob Robinson, and Dr. Alexander Kohanski, who had already made quite clear to him they wanted a hand in running the trial. Seeking a specific figure on Jewish losses under the Third Reich, Jackson was told “six million,” of which he would later recall, “I was particularly interested in knowing the source and reliability of his estimate, as I know no authentic data on it.”

You can buy The World in Flames: The Shorter Writings of Francis Parker Yockey here. [5]

Robinson, founder of the Institute for Jewish Affairs, which was sponsored by the American Jewish Congress, went on to serve Jackson as a “special consultant for Jewish affairs”; he told Jackson that he had arrived at the figure of “six million” by “extrapolation from the known statistics for the Jewish population in 1929 and those believed to be surviving now.” In other words, “six million” was something between a hopeful estimate and an educated guess; in any case, Irving notes, “given the turmoil and tragedies of a war-torn Europe ravaged by bombs and plagues, it was not a data basis on which a statistician would properly have relied.” The chicanery underlying “six million” does not end there, however.

Irving points out that the American Jewish community had raised a similar outcry about a “holocaust” a quarter of a century earlier, after World War One. In a 1919 speech, as well as in an article published in The American Hebrew entitled “The Crucifixion of the Jews Must Stop!” the Governor of New York, Martin Glynn, had claimed that “six million” Jews were being exterminated in a “holocaust.” Arthur Butz [1] [6] and Thomas Dalton [2] [6] expound even further on this talismanic “six million”; Dalton, for example, notes that throughout the First World War, in the New York Times alone, numerous references were published describing a “holocaust” involving the “extermination” of “six million suffering Jews.” Perhaps the earliest known publication of the figure dates back to an 1850 Christian Spectator article, which listed a global Jewish population of “six million.” This figure was repeated in the New York Times in 1869, to which “extermination” was added in 1872, 1880, 1889, 1891, 1900, 1901, and then to which “holocaust” was added in 1903, which continued with the descriptor “systematic” in 1905, 1906, 1910, and 1911. Dalton wryly writes that “at this point, one is tempted to ask, what is it about the Jews, such that they are subject to repeated threats of ‘extermination’?”

In late 1918, “the war to end all wars” drew to its conclusion; as Dalton remarks: “After years of dire reports about the endangered Hebrew race, did we have six million Jewish fatalities? No. Somehow, they all managed to survive. Instead of attending their funerals, we were then called upon to aid their recovery: ‘Six million souls will need help to resume normal life when war is ended’, writes the New York Times.” The “six million,” of course, was nowhere near its crescendo — it continued to be deployed, this time with reference to Ukrainian and Polish Jews, in 1919, 1920, and 1921, rapidly accelerating upon Adolf Hitler’s 1933 ascent in Germany, continuing thereafter through the War and into its current status as the new founding myth of the West in its death throes. It bears repeating that the figure of “six million” Jewish deaths in what would come to be known as “the Holocaust” nearly three decades later was reported during the Second World War, years before the egalitarian missionaries really spread their Holocaust theology. Dalton thus observes that “the figure of six million represents a sort of constant in claims or threats of Jewish suffering, irrespective of circumstances. It seems to possess a kind of magical symbolism, and hence becomes a sacred icon of Jewish persecution.” For a more detailed treatment of the myth of the “six million,” along with endless other “Holocaust” inconsistencies and impossibilities, I point the reader to the excellent work of Butz and Dalton, as well as to continuing recent exposures revealing the Yad Vashem, the official Holocaust agency of the State of Israel, and its database of purported “victims,” as a thinly-veiled hoax [7]. I would also encourage the reader to visit any of the remaining camps with an open mind, as my visit to Auschwitz did much to expose to me the unstable foundations and true colors of the Holocaust Industry.

The Allied powers met in London to draft their indictment and flesh out the details for the upcoming show-trials in Nuremberg. Irving points out that “this was, of course, a conference of the victors; their purpose was to choose the defendants, and to draft the new laws they were to be accused of having broken, and the rules of the court which was retroactively to apply those laws.” In other words, contravening centuries of Anglo-American jurisprudence, as well as the basic sense of decency that should undergird any legal proceeding, the German defendants were to punished for the violation of ex post facto laws, laws that most emphatically did not exist at the time at which they were supposed to have been broken. The final indictments handed down from these London conferences narrowly stated the “crimes,” such as “aggression or domination over other nations carried out by the European Axis in violation of international laws and treaties,” a definition that saved Soviet face; the Soviet representative had insisted that the Tribunal limit the charge even more narrowly to “aggressions started by the Nazis in this war.”

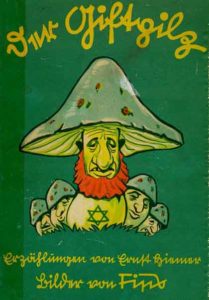

While the London conferences were underway, and while the Nuremberg Palace of Justice was renovated (it was one of the few largely undamaged buildings left in the smoldering ruins of Nuremberg), the German prisoners were concentrated at the Grand Hotel, at Bad Mondorf in Luxembourg. The Americans called the prison Camp Ashcan, while the British, determined to be unique, called it Dustbin. The horrendous treatment of Julius Streicher, the founder and publisher of Der Stürmer, along with anti-Semitic books like Der Giftpilz, provides us an illuminating example of the conditions under which the prisoners were kept. Streicher was a fairly minor figure whom the Party had essentially marginalized quite early on. His more extreme anti-Semitism was not the official Party line; indeed, an issue of his Stürmer which highlighted Jewish ritual murder was censored, the Führer considering it too lurid. The Party also censored another issue that called for the death penalty for those who miscegenated with Jews.

Streicher, a relative outcast whose only “crime” was “incitement to genocide,” or, in other words, thoughtcrime for publishing anti-Semitic material, was left manacled for five days after his initial arrest and thrown into an unfurnished, windowless cell in solitary confinement. Three times a day, his genitalia were beaten with a leather whip, and he was kicked in his testicles. His tormentors were generally, and no doubt not coincidentally, “American” black soldiers. Often, his mouth was forced open, held in position by wooden baton, and then spit in by various prison guards. He was forced to drink from a urinal, and lick the black soldiers’ feet. To add insult to injury, his nipple and eyebrow hairs were plucked, one at a time. Why was Streicher targeted such? Put simply, Irving explains, “Because of the hardcore anti-Semitism that was the staple of the Stürmer. . . Streicher became the Public Enemy No. 1 of the organized international Jewish community.”

From the early 1920s onward, Streicher had studied the Talmud, and concluded that “so long as the Jews claimed to be the chosen people, they would always find difficulties with their host nations.” Although he had personally turned away from Christianity, the Talmudic teachings about Jesus Christ, Christians, and Gentiles in general left a deep impression on him. Streicher

had perceived the Jewish Bolsheviks seizing power in Russia, murdering the Tsar and his family, and ruling by terror; he had seen the methods of. . . the Jewish ‘Soviet’, led by Kurt Eisner, in Bavaria; he had watched other Jews establish similar authoritarian regimes such as the one under Béla Kun in Hungary; and he had concluded that the Jews were making it their objective to establish final supremacy over the Gentile races by ramming multiculturalism and multiracialism down their throats. He had campaigned, in response, for the destruction of the Jews, and that no doubt was why he now found himself here.

Most of the other prisoners tried to steer clear of Streicher, “well aware of the hatred of their captors for this man. During the Third Reich, many of these same Nazis had written letters of congratulation to Streicher. . . Now they could not disown him fast enough.” Of course, not even a majority of the prisoners feigned or expressed repentance; Generaloberst Alfred Jodl, Chief of the Operations Staff for the Armed Forces High Command, when questioned about whether Hitler, a suicide in his own capital, could rightly be regarded as a famous warlord, replied, “Rome destroyed Carthage, but Hannibal is still regarded as one of history’s greatest warriors and always will be.” Hermann Göring, Reichsmarschall and Supreme Commander of the Luftwaffe, told Streicher that the Allies could not possibly assign any blame to a soldier, as every soldier must do his duty. Streicher replied, “The Jews will make sure enough that we hang.”

The Americans also forced their prisoners to watch atrocity films, many of which would later be created for the Nuremberg trials, “into which they had spliced scenes of piles of corpses filmed after air raids on German cities and aircraft factories. Some of those interned spotted the deception — one former Messerschmitt worker said he had even recognized himself.” The prisoners were maintained in solitary confinement on a near-starvation diet, with little to no medical aid, no exercise, and a panoptic surveillance regime. Letters written to their loved ones were never forwarded on, going instead to the chief interrogator. Göring, in tremendously poor health, was kept alive solely in order for the show-trial; Jackson confirmed that he intended the Reichsmarschall to die, “but not one minute before his judges decided.” Upon complaints, the commanding officer of the prison stated that the Geneva Convention was inapplicable, for “you are not a captured officer nor a prisoner-of-war. The Army, the Navy, and the State of Germany have ceased to exist. You are entitled to nothing.”

A committee of American psychiatrists and neurologists contacted Justice Jackson, seeking an opportunity to examine the German prisoners and again pathologize the German people and white ethnocentrism in general. They wrote:

Aggressive leaders have been recurrently produced by the German people, who then follow them blindly. Detailed knowledge of the personalities of these leaders would add to our information concerning the character and habitual desires of the German people, and would be valuable as a guide to those concerned with the reorganization and re-education of Germany.

These “doctors” then recommended that “the convicted be shot in the chest, not in the head,” as it would be valuable to autopsy their undamaged brains. Jackson, who had read one of the applicants’ books, Is Germany Incurable? and enjoyed it, agreed, reflecting that, “after conviction, [a] finding of insanity, perversion, or other mental defect on the part of these leaders would do more to deflate their future influence in Germany than anything else could do.”

Jackson’s primary concern was “whether the prosecution could obtain enough admissible evidence to support the charges which had been leveled so freely against the Nazis throughout the war.” As can be expected when searching for evidence of an event that did not occur, garnering usable documentary evidence became a mounting nightmare for Jackson. Adding to this conundrum, the difficulty of which speaks volumes, was his recognition that the Americans could no longer sit next to the Russians and hold court over the Germans for offenses like looting a conquered country’s wealth. This hypocrisy was on garish display when Jackson finally visited Berlin. Irving describes that the fallen capital “had crumpled into shapeless heaps of rubble, the stinking remains of former palaces, museums, churches, and apartment buildings under which thousands of bodies still lay buried. . . there seemed to be no young men; everywhere were lines of women toiling through the ruins like ants in an anthill, clearing away the rubble, hammering and cleaning bricks and masonry.”

Jackson wrote that “the streets were lined with dumb-looking people, most of them moving their possessions, some going in one direction, some in another.” There were a multitude of horse-drawn carts, too, each with a Russian at the reins; Jackson thus saw that “the systematic plundering and stripping of the country was continuing apace.” The Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann implored Jackson to let Jews make a special presentation of “their case” at the trial, but the Justice, concerned with optics, strongly advised against this proposed addition to the spectacle. Jackson felt that his prosecuting staff was already overloaded with Jews. Coming from a country where a substantial proportion of the legal profession was already recognizably Jewish, a percentage that would multiply over the next decades, he recognized the risk he ran. He was “most anxious that this should not be interpreted as a vengeance trial.”

In the actual courtroom presentation, Jackson included one Jew on the American team, Robert Kempner; the other Jews were kept behind the scenes, as when Streicher observed the full American staff, he noted that there were “nothing but Jews among the Americans.” Kempner was a German Jew who had fled the country in 1935; returning now to Nuremberg in 1945, Kempner swore “revenge at any price.” Preparing his portion of the case for the prosecution, Kempner frequently resorted to threats and coercion to get witnesses to change or withdraw inconvenient evidence. Dr. Friedrich Gaus, Ribbentrop’s legal adviser, was one. Irving explains that Gaus would suddenly be stricken with “amnesia” about the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, the signing of which he had actually witnessed in Moscow.

Gaus later testified that Kempner had threatened to turn him over to the Russians. Kempner’s malfeasance did not end there, as his behavior with “evidence” was also “highly questionable”; for example, he would later turn up in German foreign ministry files the original Copy No. 16 of the Wannsee Protocol, and bestow upon it a wholly undeserved reputation as a key document in the Final Solution of the Jewish problem. Despite the aura which now surrounds it, the document contains no reference to any supposed killing of Jews. It is complete with Geheime Kommandosache rubber stamps. Not only did the RHSA, the agency supposedly originating the document, use the civilian classification Geheime Reichssache on its documents, but the statistics contained in the document, Irving notes, “bore little relation either to each other or to reality.” The Tribunal also heavily relied upon the fraudulent [8] “Hossbach Protocol” to assert that Hitler and his “henchmen” had engaged in a sinister “conspiracy to wage aggressive war” and conquer the globe.

A Reich chancellery document proved that the Führer had “repeatedly” commanded that the solution to the Jewish Question (no, this does not mean some genocidal “Final Solution” that plays on a perpetual loop in the Jewish psyche) be “postponed until after the war was over”; Irving notes that “this did not suit Kempner at all, and when the file was returned to the document center, this particular photostat was missing.” In fact, the only reason that we are aware that this file ever existed is because it was briefly summarized in the routine “staff evidence analysis sheet” produced by the Nuremberg document experts.

Working with Irving, the German historian Eberhard Jäckel was able to find and secure the original document. Wilhelm Stuckart, a former Party attorney and Reich Interior Ministry official,

would later succeed in turning the tables on Kempner: hinting in 1947 that he had incriminating evidence against him, a pre-war document stored safely away, he would bring Kempner. . . to his knees. . . Stuckart boasted to his fellow inmates at Nuremberg that he was going to walk — and walk he did, sentenced to the time already served.

Kempner did not walk the earth for much longer, though, for he was killed in a still-unexplained “car accident” near Hanover in 1953.

The Chief Soviet Prosecutor, Iona Nikitchenko, was appointed as the Soviet judge; as Jackson observed, “he picked out the men to be prosecuted, so it is hard to see how he can be an impartial judge.” Nikitchenko was an experienced kangaroo jurist, having presided over many of Stalin’s show trials during the pre-war Great Purge. Similarly, former Attorney General Francis Biddle was appointed as the American judge; during his time in office during the prosecution of the war, Biddle had also pre-selected some of the Nuremberg defendants. The American position was further complicated by Truman’s completely unjustified, unnecessary [9], and evil annihilation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

As the crater once known as Germany smoked, as her people were raped, starved, and slaughtered, the Allied prosecutors lived lives of luxury; they appropriated nicer homes and apartments that still stood amidst the blood-spattered rubble and joined the Russians in their pillaging. The overwhelming majority of the private papers of Adolf Hitler, Eva Braun, Hans Lammers, Heinrich Himmler, Göring, and Jodl vanished into unknown hands of Allied looters, while Kempner illicitly acquired all of Alfred Rosenberg’s papers. Jackson was chauffeured around town in the limousine of Joachim von Ribbentrop, the Nuremberg defendant who had been the Foreign Minister. Of the British and French prosecuting teams, Jackson’s son wrote, “Those boys are out for blood. They’ve even suggested we use a guillotine!” Irving reports that “there is anecdotal evidence that in the forests outside Nuremberg, the prosecutors made a bonfire one day of all the mitigating documents which would have aided the defense case.”

From left: Hitler, Jodl, and Keitel.

Jackson thought it “unfortunate” that inevitably, “the victors must. . . seem to be sitting in judgment on the vanquished,” but argued that “the scale of [the German] attack leaves no neutrals in the world.” In the United States, strong legal doubts began to be voiced, and Jackson’s mail began to contain letters of condemnation from colleagues of the American Bar, who felt that he had degraded the Supreme Court by accepting the role of chief prosecutor in a political show-trial. As Irving adroitly summarizes:

Not only were the Allies seeking to convict their enemies under laws which had not existed at the time of the alleged offenses, but. . . they were specifically ruling out a number of obvious defenses which could not have immediately been raised: the German soldiers [were not permitted] to plead that as soldiers in a Führer state, they were bound to obey the orders that were issued to them; nor could they point out that on more than one occasion each of the prosecuting powers had committed precisely the same crimes as they were alleging against the Germans.

The ex post facto nature of the Nuremberg “indictments” troubled many legal minds, including Senator Robert Taft and Justice William Douglas, who saw that the Allies were “substituting power for principle.” Chief Justice Harlan Stone wrote that, while he personally “would not be disturbed if the victors put the vanquished to the sword as was customary. . . he was disturbed to have this action ‘dressed up in the habiliments of common law.’” He continued: “Jackson is away conducting his high-grade lynching party in Nuremberg. . . I don’t mind what he does to the Nazis, but I hate to see the pretense that he is running a court and proceeding according to common law. This is a little too sanctimonious a fraud to meet my old-fashioned ideas.”

The final indictment issued from London ran to twenty-five thousand words, composed in highly sensational, lurid, and emotional language, containing “allegations which no serious historian would now unblushingly venture to sustain, but which were designed to feed the appetite of the mass media.” There were absurd allegations, such as the charge that the Führer had threatened to kick British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in the stomach before the press photographers, and the claim that Germany had drawn Japan into the war. One of the charges was “conspiracy to commit aggression against Poland,” conveniently eliding over the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the nonaggression pact by which Hitler and Stalin carved up Eastern Europe and the Baltic states. Additionally, this and other “conspiracy to commit aggression” charges ignored the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran, as well as the Winter War that resulted from the Soviet invasion of Finland.

The defendants were also indicted for the German invasion of Norway, a plan which Churchill had actually been just about to enact when Hitler merely beat him to the punch. Germany was charged for the mass deportation of populations, while simultaneously the Allies ethnically cleansed millions of Germans from East Prussia, Pomerania, Silesia, and other territories of the fallen Third Reich. The Allies made no mention of their enforced starvation of civilian populations during the war all while these indictments were drafted and throughout the duration of the Nuremberg proceedings. The Chief Soviet Prosecutor, Roman Rudenko, went on to become the commandant of a notoriously brutal NKVD “special camp” installed at the former Sachsenhausen concentration camp at Oranienburg. At least twelve thousand German prisoners were butchered here by Soviet forces under Rudenko, the majority of which were women, children, and the elderly.

Rudenko submitted false documentation to pin the responsibility for the Soviet Katyn massacre, in which over twenty thousand Polish intellectuals and officers were decimated, on the Third Reich. Because this was such a blatant falsehood, the Katyn massacre did not make it into the final indictment. Perhaps even more cynical, though, was the Allied indictment of Germany for the use of slave labor, as President Roosevelt himself “had indeed approved at Yalta the deportation of the Soviet Union of hundreds of thousands of able-bodied Germans as slave laborers.” Churchill approved of the practice as well, and actually sold some of the Germans in their occupied territory to the Soviet Union. This enslavement did take place, and is well-documented; an infinitesimal fraction of those hundreds of thousands of Germans ever returned home. The Americans also quite literally sold Italian prisoners for use in Belgian coal mines and maintained a similar slave trade with France, which was only halted because the French treated their German slaves so abominably.

The American Office of Strategic Services, or OSS, the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency, worked alongside Army attorneys to prepare materials for the Nuremberg trials. Irving notes that the private files of Justice Jackson provide disturbing evidence of tampering with and distortion of evidence. After the main atrocity film, The Nazi Plan, was shown to Jackson’s prosecutorial staff, they warned him that it was largely exculpatory, and that as such it would have to be extensively cut.

One lawyer wrote the Justice that “I would in the cutting process eliminate the scenes which follow the [German] movement across the border in Austria, Sudetenland, and the Rhine, in all of which flag-waving, smiling faces, and the presentation of flowers help to nullify our notion that by these acts the people were planning or waging a war against their neighbors.”

The film produced about the Warsaw Ghetto showed the Jewish ghetto police collaborating with the Nazis, and thus was suppressed, along with one purporting to show “Reichsbank loot” at Frankfurt, with no evidence that the loot had come from concentration camp victims. Of course, there were too many far-fetched, demonstrably fictional atrocity tales to even attempt to examine them all; again, I point the reader to the work of Butz and Dalton for a more complete investigation. One example is an affidavit by a Polish member of the United Nations War Crimes Commission, swearing that Jews had been killed by steam alone at Belzec. Three members of Jackson’s staff swore an affidavit stating that there were lethal gas chambers at Dachau, at which there were none.

One subordinate of Kempner on the American team wrote: “Imagine making dentists pull out all the gold dental work from the teeth of victims. . . while still conscious! We have pictures of a soap factory where they hit the victims. . . and the heads are cut off and boiled in one vat and the bodies in other vats.” The International Military Tribunal credulously and gleefully accepted the “legend first inspired by the brilliant Soviet propagandist Ilya Ehrenburg to the effect that the Nazis had fabricated soap from the remains of their victims, and even stamped the soap with the initials RJF, ‘pure Jewish fat.’” The Soviet prosecutors even submitted “soap samples” for evidence; Irving remarks that, “for years since, such bars of soap have been part of an unwholesome trade among curiosity-collectors in Israel, and occasionally some are even ceremonially buried to the chants of the kaddish.” Irving emphasizes the almost comically ludicrous nature of the “soap” legend, commenting, “Why the Nazis should have wanted to rub their faces in the boiled-down detritus of their sworn enemies remains an imponderable mystery.” Konrad Morgen, a former Schutzstaffel (SS) Judge Advocate, refused to give perjured testimony to the effect that Ilse Koch, widow of the Buchenwald and Majdanek commandant, had fashioned lampshades from Jewish skin. Morgen said that it was a “totally untrue” legend, and noted that “the Americans almost killed me. They threatened three times to turn me over to the Russians or French or Poles.”

You can buy It’s Okay to Be White: The Best of Greg Johnson here. [10]

It swiftly became apparent to Jackson that the OSS “had intended all along to stage-manage the whole trial along the lines of an NKVD show-trial, with Jackson little more than a professional actor. . . they proposed to run a pre-trial propaganda campaign in the United States, with ‘increasing emphasis on the publication of atrocity stories to keep the public in the proper frame of mind.’” As part of this stage-management, the OSS proposed a “black propaganda” campaign throughout the trial, “with agents in selected foreign countries starting rumors designed to influence public opinion in favor of the trial and against the defendants. This would be far more effective. . . than mounting a straightforward public relations campaign which would obviously be seen as emanating from the powers conducting the trials.” To this propaganda campaign, Jackson told his staff that “the scheme is cock-eyed. Give them no encouragement.”

It turned out that the OSS would not have to work quite so hard to rig an already rigged show-trial, for the Allied Tribunal had already engaged in abundant skullduggery in their drafting of the rules of evidence and procedure. At the pre-trial interrogations, the defendants were not accompanied by lawyers, and were frequently persuaded by trickery or intimidation to subscribe to testimonies incriminating others which we now know to have been false. Among the Nuremberg files are anonymous typed extracts of documents instead of originals, and sworn statements by witnesses like [Rudolf] Höss, commandant of Auschwitz, in which all the “witnesses to his signature” have signed, but not Höss himself. The Americans also submitted a file of invoices for substantial monthly consignments of Zyklon supplied to the pest-control office at Auschwitz; they concealed the fact that the same file contained invoices for identical quantities of Zyklon delivered to the camp at Oranienburg where it was never alleged there had been any gas chambers.

The published Nuremberg archives do not include a single one of the more than three thousand affidavits sworn by witnesses for the defense. Among these records, the published transcripts are especially “erratic, erroneous, and incomplete,” as well as blatantly doctored. Any documents potentially damning with respect to the Allies were whisked away, and defense counsel was only allowed to use in “court” the pre-screened documents presented by the prosecution. The defendants’ attorneys were routinely surveilled, harassed, and intimidated with press attacks and ransacked offices. Witnesses for the defense were housed in prison camps or scarcely better detention centers, if they were even contacted at all; in most cases, when defense counsel named a witness, the Tribunal simply declared them untraceable.

SS Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff was held for a year in a lunatic asylum, while Field Marshal Erhard Milch was removed to the punishment bunker at Dachau for his offering evidence in defense of Göring and Albert Speer, architect and Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production. The defense was not allowed an opening statement, and was only allowed a brief concluding speech, followed by the lengthy closing statements of the prosecution, to which the defense was not allowed to reply. Moreover, Justice Jackson promised that, in the “almost impossible” event that a defendant was acquitted, that man would be turned over to “our Continental allies.” The three men eventually acquitted were sent to nominally “German” courts.

Conditions in the Nuremberg prison were hardly better than Camp Ashcan. Streicher, for example, was still compelled to wash his face and brush his teeth in his toilet. Mental breakdown continued, compounded by the suicide of Robert Ley, head of the German Labor Front. Inexcusably, the Nuremberg defendants’ wives, mothers, sisters, and other womenfolk were imprisoned, their children placed in orphanages and foster homes. On seeing a newspaper report stating that “the defendants looked tired and nervous,” Streicher reflected:

Let one of these gentlemen of the press sit for three months in a prison cell with hardly any daylight and under a dim electric bulb for two hours each evening with his pen or pencil with only fifteen. . . minutes a day outside in the prison yard and being wakened all night long by sentinels who are always looking in, then he too might look a bit tired and nervous when this show-trial began.

He continued that “in this trial, there is no question of according to the defendant a blind and impartial justice; the trial has been set the task of giving to an injustice a veneer of legality by cloaking it in the language of the law.”

Up until the very last possible moment, members of the Tribunal wanted to charge more defendants; for example, Jackson’s lead counsel urged that the German geopolitician Karl Haushofer be indicted, laughably named as “Hitler’s intellectual godfather,” but Jackson rightly suggested that it would look bad for the Americans to start hanging academics for their views. Any graves left vacant would soon be filled, however, by dozens of subsequent Allied “trials” and by decades of Israeli Mossad assassinations. Asked for the purpose of the trials, Jackson declared that

we want to prove to Germany and to the world that the Nazi regime was as wicked and as criminal as we have always maintained. We want to make clear to the Germans why our policies toward them will have to be very harsh indeed for many years to come.

As the trials finally commenced in Nuremberg, “a cheerless place to live in, let alone to die,” Justice Robert Jackson delivered his opening speech, still regarded as his finest hour of oratory, and his last successful moment for the duration of the proceedings. In his speech, Jackson said that the Nazis had killed 5.7 million Jews; Irving muses that this figure surely had sounded more precise to him than the “six million” fraud.

One of the most flagrant forgeries introduced as evidence was a document book which contained an account of a “secret meeting” wherein Hitler ordered genocide against Poland, to which Göring “jumped on the table” and “danced around like a savage.” To this hogwash, Irving notes that “the sheer improbability of the 264-pound Göring ‘jumping on a table’ was overlooked in the prosecutors’ glee, as was the fact that Hitler had not ‘liquidated every member of the Polish race.’” The document was a forgery, made available by the Associated Press journalist [and Pulitzer Prize winner] Louis Lochner. The British judge, evidently believing the Allied treatment of the Nuremberg defendants to be excessively generous, asked, “Do you think we would have been given anything like this if Germany had won the war?”

The prosecutorial teams and the judges hobnobbed every week, indeed almost nightly, in yet another egregious violation of the accepted norms of jurisprudential ethics. At one such banquet, Andrei Vyshinsky, one of the Soviet prosecutors, who had in fact served under Soviet judge Nikitchenko in the prosecution of unfortunate Russians fallen afoul of Stalin during his Great Purge, led a toast in Russian. Everybody, Tribunal judges and prosecutors alike, raised their glasses to Vyshinky’s toast, “To the defendants. May their paths lead straight from the courthouse to the grave!” In fairness, Irving adds that “the judges had drunk of their champagne before the translation reached them. Jackson later professed himself hideously embarrassed. . . [but] so it went on throughout the trials. The judges and prosecutors were constantly guests at each other’s tables; the defense lawyers were never invited.” Judge Francis Biddle reminisced about a dinner at the residence of Chief Soviet Prosecutor Rudenko, writing, “Much vodka and fun!”

Upon being shown the ridiculous and incontestably fabricated atrocity films, many of which had been produced by overlapping groups of Communists and Jews, the defendants were aghast; clearly, none of them believed or even had been aware that anything like the depravity depicted onscreen had ever happened. Ribbentrop, shown a Daily Mail article featuring a Russian report on supposed findings at Majdanek, asked his son Rudolf, a Waffen SS officer, what truth he ascribed to it. The younger Ribbentrop said, “Father, this is the same kind of atrocity story as the Belgian children with the hacked-off hands after World War One.” Most of the more florid atrocity tales came from “confessions” that were almost uniformly extracted by Soviet torture; if one examines these “confessions,” he will find that they are riddled with factual errors, impossibilities, and other inconsistencies that strongly suggest that they were obtained under duress. Some of the most shocking and incoherent admissions came from Auschwitz commandant Höss, who, before being turned over to the Poles for execution, attempted to have a letter smuggled out to his wife in which he apologized to his family for “confessing” to false atrocities, stating that he had been tortured.

His letter was never delivered, and is still in private hands in America.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [11] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Don’t forget to sign up [12] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.

Notes

[1] [13] Arthur R Butz, The Hoax of the Twentieth Century: The Case Against the Presumed Extermination of European Jewry. York, Pennsylvania: Castle Hill, 2015.

[2] [14] Thomas Dalton, Debating the Holocaust: A New Look at Both Sides. York: Castle Hill, 2020.